Scientists can’t believe what’s happening to South Louisiana marsh bass. Anglers could be in for double-digit catches in the next few years.

Lately, I have been seeing social media posts from speckled trout-centric anglers who have also begun fishing the marshes around New Orleans for chunky largemouth bass, aka marsh bass. Has the marsh bass really outgrown its kid brother title of “Green Trout” and been elevated to a target species for inshore anglers?

Inshore Louisiana fishermen are a demanding bunch, and a target species must be good to eat, plentiful, and sporting to catch. Based on the social media posts I’m seeing, the inshore crowd is very satisfied with the marsh bass as table fare, and the fish has become plentiful from the Rigolets, all along the MRGO channel, and from Hopedale to Delacroix. What about the last criteria? I think most fishermen would classify a bass as sporting to catch, if it’s about 2 lbs. or larger. So will this generation of plentiful 12-inch marsh bass grow large enough to secure a lasting place in the club of universally-targeted inshore species along side speckled trout and redfish?

You may be saying to yourself that marsh bass can’t grow as heavy as the standard largemouth bass found in southern lakes, but according to two researchers from LSU, Michael Meador and William Kelso, the growth rate of older marsh bass equalled or exceeded the growth rate of largemouth bass taken from a number of Louisiana oxbow lakes.

Louisiana Sportsman has reported a number of 10 lb. and heavier bass caught in the Bayou Bienvenue area over the last two years. So, it’s apparent that if the marsh bass survives into adulthood, their growth rates are adequate to bring them to a trophy size.

This is great news for inshore anglers, but marsh bass do face major obstacles to growing as large as their freshwater cousins.

Water salinity creates a huge barrier to the growth of trophy bass in the marsh. LSU researchers, Meador and Kelso, studied the effect of salinity concentrations on marsh bass and how it effects their seasonal abundance, movement, and health.

They found that marsh bass prefer a salinity of 3 parts per thousand (ppt). Surprisingly, growth rates in marsh bass did not decrease in salinity as high as 8 ppt. However, in salinity of 12 ppt, the bass stopped eating after 1 week and subsequently died.

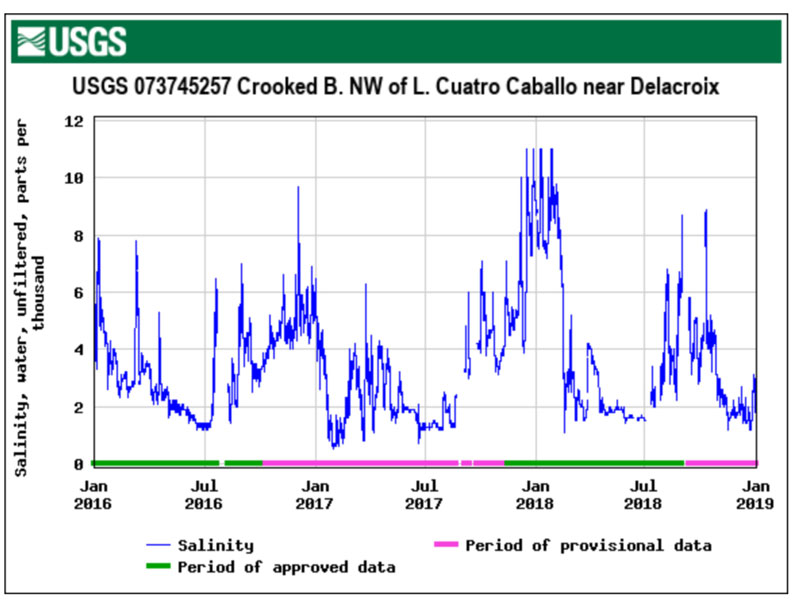

I pulled salinity data from 2010 to the present from the USGS Crooked Bayou station, located on the north side of Lake Cuatro Caballo, aka Four Horse Lake, and 6 miles southeast of Delacriox Island. This is not an area known for marsh bass, and it’s relatively close to Breton Sound where the salinity regularly becomes much too high for bass. However, it’s helpful to look at salinity here, since it can be considered a boundary area of habitat acceptable to marsh bass.

In the Chart 1 we can see that during most years there are many sustained periods of salinity above 8 ppt at the Crooked Bayou station. If you are wondering why the salinity periodically spikes, it’s because of the Mississippi River water level. When the river is low the salinity goes up in the marsh and vice versa. Therefore, salinity is typically high in the fall or early winter when the river is low.

Periods of high salinity will move the marsh bass toward fresher water, which on the east side of the Mississippi River means they get pushed up against the river levies or into areas behind levies. This movement results in a greater concentration of fish, and thus periods of hunger when the bait resources are overcome.

Periods of high salinity will move the marsh bass toward fresher water, which on the east side of the Mississippi River means they get pushed up against the river levies or into areas behind levies. This movement results in a greater concentration of fish, and thus periods of hunger when the bait resources are overcome.

Bass will continue to grow throughout their life if enough food is available, but they can not make up for periods of hunger. Even if they survive, they will not have enough time to reach trophy size, if they are subjected to regular periods of hunger. Therefore, it’s most helpful to look at salinity during periods of low Mississippi River level as an indicator for marsh bass growth.

Interestingly, the salinity concentration range from 2016 to present looks different than the prior 5 years.

In the Chart 2 below, we can see that the highest salinity was 11 ppt during the early winter of 2018, and it only reached 11 ppt for short periods of time. The salinity during other periods of low Mississippi River levels was well within the range where marsh bass can flourish, such as in fall of 2016, when salinity was mostly lower than 6 ppt.

It’s important to restate that the area around Crooked Bayou station is outside the expected habitat area for marsh bass, but even here, the salinity since 2016 has mostly been within an acceptable range.

It’s important to restate that the area around Crooked Bayou station is outside the expected habitat area for marsh bass, but even here, the salinity since 2016 has mostly been within an acceptable range.

Case in point, on January 16, 2017, I caught a bass in Lake Fausan that was around 5 years old, based on typical growth curves from fish biologists Dave Willis and Bob Lusk . Lake Fausan is 3.4 miles southwest of the Crooked Bayou station.

To better understand whether this change is temporary or long term, we need to find measurable factors that we can correlate with the recent, lower than expected salinity when the Mississippi River is low. Tracking these drivers and comparing them to marsh bass catches will be one way to verify a possible habitat expansion.

Since the Mississippi River discharge is the primary driver of salinity change in the estuary, the first point of clarification is whether the salinity changes from 2016 to present are solely due to higher Mississippi River discharges.

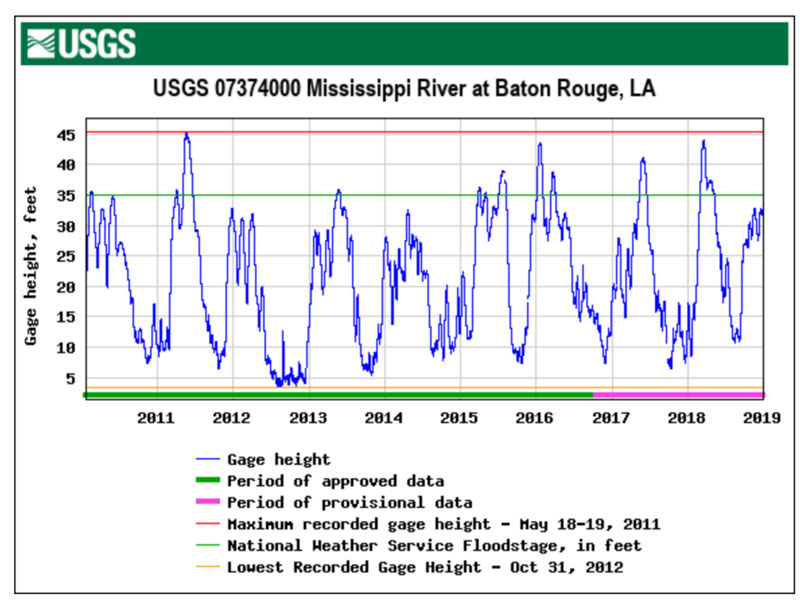

I have pulled river level data from 2010 through 2018 at the USGS Baton Rouge gauge, which is shown below in Chart 3.

We can see that in the 2016 to 2019 period, the river rose and fell seasonally as it did from 2010 to 2015. It’s evident that the maximum river levels were higher from 2016 to present than the average for the entire period, but the important factor, the minimum river levels, were not significantly different than during the 2010 – 2015 period. Based on what I see in the Mississippi River data, I don’t believe that the river level alone can explain the lower salinity at Crooked Bayou.

We can see that in the 2016 to 2019 period, the river rose and fell seasonally as it did from 2010 to 2015. It’s evident that the maximum river levels were higher from 2016 to present than the average for the entire period, but the important factor, the minimum river levels, were not significantly different than during the 2010 – 2015 period. Based on what I see in the Mississippi River data, I don’t believe that the river level alone can explain the lower salinity at Crooked Bayou.

After a review of data from USGS Water Resources and the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation (LPBF), I believe that the combined freshwater flow rates of the Pearl River and the Mardi Gras Pass are measurable factors we can use for predicting habitat size.

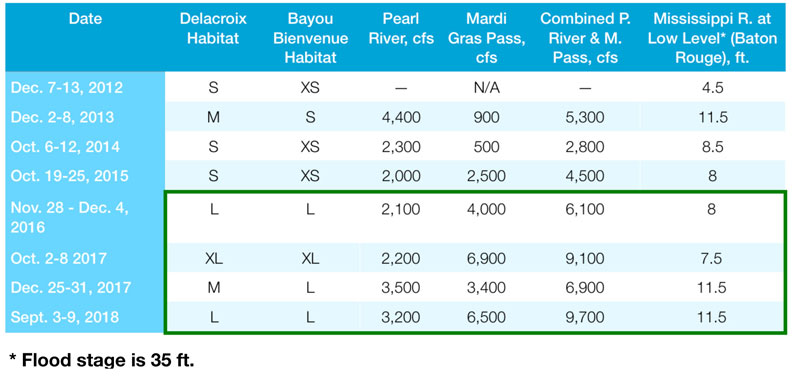

I have populated Table 1 on the following page with data from LPBF’s salinity maps, and only chose data from the periods of low Mississippi River water level for the reasons stated above. I used a convention of X-Small to X-Large as a qualitative measure of the size of the marsh areas where salinity is within a healthy range for marsh bass. I also added Mississippi River levels in the table, so that we can evaluate the affect of river level on the habitat area.

The green box in the Table 1 outlines the time period when the marsh bass habitat is expanded. We can see that the discharge rate of the uncontrolled Mardi Gras Pass has been increasing since it opened in 2012, and is significantly higher during the period since 2016.

The Pearl River alone has an affect on bass habitat, especially in the Bayou Bienvenue area, and this is visible in the data from 2012 through 2015. However, I believe that the factor to watch is the combined discharge rates of the Pearl River and the Mardi Gras Pass.

The Pearl River alone has an affect on bass habitat, especially in the Bayou Bienvenue area, and this is visible in the data from 2012 through 2015. However, I believe that the factor to watch is the combined discharge rates of the Pearl River and the Mardi Gras Pass.

We can see in the data that when the combined discharge rates of the Pearl River and the Mardi Gras Pass are above 6,000 cfs, the marsh bass habitat is expanded.

Further, I believe the increasing affect of the Mardi Gras Pass is seen by looking at the relationship of the Pearl River discharge and the habitat around Bayou Bienvenue. When the Mardi Gras Pass discharges are low prior to 2016, the discharge rate of the Pearl River had a direct impact on the Bayou Bienvenue area habitat. But, after 2015, the Mardi Gras Pass discharge had reached a high enough rate that low Pearl River discharge rates no longer reduced the size of the habitat around Bayou Bienvenue.

We also have to consider that these bass are living in a wilderness and they are in the middle of the food chain. Jerald Horst wrote an informative paper on the marsh bass where he points out the predation risks bass face from larger predators.

These include alligators, alligator gar, redfish, bull sharks, dolphin, and others. Predation impacts the size of the marsh bass because they need to live a long life to reach a trophy size. For example, Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries reports aging a female bass in 2009 that was 11 years old and weighed 9.16 lb. So predation and consequently access to safe cover is a significant factor in the growth potential of marsh bass.

However, there is a link between lower salinity in the marshes and increased cover in which bass can hide to avoid predation. Louisiana DWF reports that decreased salinity in the marshes increases the growth of submerged vegetation. This in turn, decreases the rate of predation on marsh bass, and increases recruitment of the juveniles.

So if a marsh bass can avoid getting eaten, and have an adequately large habitat area with plentiful food and where the water salinity stays below a critical concentration, which is somewhere between 8 and 12 ppt, they have the potential to grow to a respectful size before they succumb to old age.

So in conclusion, I’m hearing about many bass being caught in the marshes east of the Mississippi River, and some of them are becoming respectable in size. It also looks to me like the salinity concentration on the east side of the Mississippi River has become more favorable for the expansion of the marsh bass habitat, and the longer this continues, the bigger the bass will grow. The real proof of this change will be catches of larger marsh bass over the next few years.