The magnificent bryozoan in all its wonder

“Ugh; It looks like a brain, man,” my fishing partner said, peering into the swampy water and gingerly poking a gelatinous-looking blob with a boat paddle.

It dawned on me earlier that, while he was an expert speckled trout fisherman, he had virtually no experience in freshwater fishing.

When we stopped to buy crickets for a bream-fishing trip, he wrinkled his nose.

“You mean, we’re really gonna fish with bugs — BUGS!” he said.

Of course, no speck fisherman would dream of using insects for bait.

What he was nudging at the moment, however, was a moss animal known as the magnificent bryozoan (Pectinatella magnifica).

The blob wasn’t just a single animal, but an entire colony of animals, all genetically identical and fused into an irregular ball as large as a basketball.

These colonies are very firm to the touch, in spite of their gelatinous appearance. They don’t resemble anything living, especially an animal.

Freshwater fishermen often see them, but because of their repulsive appearance they usually avoid touching them and simply go on their way with a shrug of their shoulders.

The magnificent bryozoan is a member of an interesting but little-known group of animals collectively called ectoprocts or simply bryozoans. In total, about 5,000 bryozoans are known to science, but most of them are marine. Only about 50 species live in freshwater.

The name “moss animal” is not very descriptive for the magnificent bryozoan, but it is applied to the whole group because many of the marine species resemble moss.

Others grow in crusty or branchy shapes, and their colonies have hard exteriors. Many of the growths seen on coral reefs are not coral at all, but rather are bryozoans.

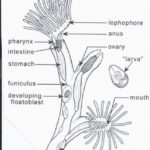

The name “ectoproct” is descriptive and means “outside anus” in Greek. They are so named because the anus of each animal (see accompanying drawing) is located outside the food-gathering arms called lophophores.

A smaller group of closely related colonial animals are classed as entoprocts.

The blobs fishermen see in the water are composed of thousands of living bryozoan animals called zooids that live on the outside of the form, but fishermen are not likely to ever see them.

These zooids are only .02 inch long. They almost instantly retract their tentacles and mouths into their “body” at the first hint of danger, so it is unlikely that a person could get close enough to see them in the wild.

Retraction takes 60 milliseconds.

When danger passes, they pop their tentacles out using water pressure.

Bryozoans are very simple animals. The tentacles of an individual zooid, collectively called a lophophore, surround the pharynx or throat of the “mouth.” The tentacles are covered with tiny cilia (hairs) that create a current that draws food items to the mouth.

The digestive tract is U-shaped. Food passes through the pharynx into the stomach, and then through the intestine and out the anus.

Food for these filter feeders consists of microscopic particles, mostly phytoplankton.

A primitive nerve called a “funiculus” runs the length of each animal. Sperm and statoblasts (labeled in the graphic “developing floatoblast”) develop along the funiculus. They have no gills, heart or blood.

Because of their small size they can absorb oxygen and dump carbon dioxide by diffusing it through their body walls.

Nor are there nephridia (primitive kidneys). Ammonia is diffused out through the body wall and lophophore.

Interestingly, small openings exist between adjacent zooids so they can share food with each other. Colony members are genetically identical and cooperate, like the organs of a more-complex animal.

Zooids of the magnificent bryozoan are simultaneous hermaphrodites, meaning they are male and female at the same time. When sperm and egg unite, it produces a so-called larva, different than what is normally referred to as a larva. Two or more zooids are in each larva.

Within 24 hours of their release, larvae settle out on a hard surface to grow. Magnificent bryozoans are very partial to anything wooden — sticks, branches, and logs.

The colony immediately and rapidly begins to “grow,” which it does by budding new zooids off the earlier ones.

New zooids form on top of the older ones, which die and turn into the jelly-like interior mass of a colony. This interior mass is 98 percent water.

Because all the zooids in a colony were cloned from an original larva, they are all genetically identical.

Bryozoans don’t put all their reproductive tricks into one hat, however. Every colony produces disc-shaped statoblasts: masses of cells identical to the colony that serve as “survival pods.”

Statoblasts are tough and can survive drying out, freezing and long periods of dormancy. If the parent colony dies or is destroyed, a statoblast’s shell opens and the cells inside develop into a zooid that tries to form a new colony.

This is important because water temperatures below 60 degrees will cause a magnificent bryozoan colony to disintegrate and fall apart, which of course releases the statoblasts to begin a new colony when warm weather returns.

Statoblasts come in different forms. Some, called “floatoblasts” float. Others sink and are called “sessoblasts.” Others stay in the remnants of the disintegrated colony.

Bryozoans have few predators, although insects and fish are noted to feed on them occasionally. Probably their most-aggressive predators are apple snails. These big (apple-sized) freshwater snails are an exotic species that has been introduced into southern U.S. waters from Latin America.

Magnificent bryozoans have been referred to by humans as alien pods, strange animal eggs, mysterious blobs, humongous fungus and weird or disgusting.

If anglers knew how cool they were, they would pause a moment during fishing to admire them.