March has always been crappie month. It is the time when these popular game fish school and move toward the shallows for spawning.

They are caught in significant numbers, and crappie are among the tastiest of freshwater fish.

Of course, there is certainly nothing wrong with bass or catfish filets, and for me a fried bluegill is almost as good as crappie. Notice I said “almost.”

Clearly the popular vote goes to the crappie, a fish so desirable many are willing to pay top dollar for it. For wildlife agents, this is where the trouble begins.

Crappie have game-fish status and may be not be taken with nets or sold in Louisiana.

But the law does not stop the illegal taking or selling of crappie, and at times throughout recent history, black markets at both interstate and intrastate levels have thrived.

Books, newspaper and magazine articles have been written about large-scale illicit interstate crappie markets, and I hear another book may be on the way.

So I won’t attempt to address the big-time operations here, other than to say that undercover wildlife agents risk their lives and put forth Herculean efforts to end some of those criminal endeavors.

Instead, we will look at typical methods used to take crappie illegally or in excess of the limit and how wildlife agents deal with the problem. We will also look at all-too-common small-scale illegal game-fish sales and how they are addressed.

The common methods for taking crappie illegally are gill nets and hoop nets.

Both are extremely effective, although they catch in different ways. Gill nets used are of the 2-inch mesh variety, 1-inch smaller than the legal minimum used in freshwaters areas for the legal harvest of freshwater commercial fish.

Only a very large crappie will entangle or “gill” in 3-inch webbing, but the 2-inch version will get the smaller fish.

One problem for the gill net outlaw is it’s hard to hide 100 yards or more of gill net. So the net has to be fished in a secluded place away from prying eyes.

The other problem is that time is not on the outlaw’s side: Fish entangled in the gill net won’t live very long and must be retrieved before spoiling. Maximum fishing time on a gill net is 10 to 12 hours, so they are usually set out and hauled in at last and first light or set and retrieved at night.

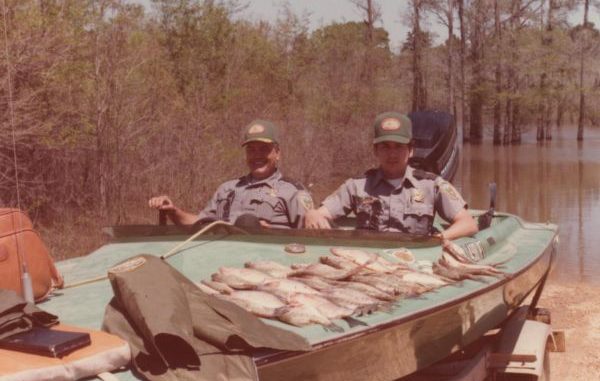

If wildlife agents suspect or are tipped about illegal gill nets, they have a good chance of catching the outlaw by setting up surveillance on the net or catching him returning to his launch with the net and crappie on board.

Hoop nets are different. For those readers unfamiliar with the hoop net, it is basically a cylinder-shaped trap constructed of netting stretched over a series of three to five hoops. The hoops might be no more than 2 feet in diameter, but some go up to 8 feet.

Netting is usually 1-inch mesh, but some of the larger nets used for taking big commercial fish may wear mesh of 2 inches or more.

Within the cylinder are one or two funnels allowing fish to swim in but not out.

Hoop nets are stretched out and placed below the surface near a point or some other natural terrain formation where fish will travel or congregate. If current is present, they are placed with the entrance end facing downstream so fish swimming up current will enter the net.

Smaller hoop nets of 2 to 4 feet in diameter with 1-inch mesh are best for crappie but are very commonly and legally used for catfish.

Stopping illegal use of hoop nets is not easy. For one thing, they are hard to find because they can be fished completely below the surface.

The next problem is time, which is on the outlaw’s side with this gear. When water temperatures are low, as they are in late winter and early spring, fish will easily survive in a hoop net for a week or more — many times much more.

So if the outlaw sees or hears of a game warden snooping around, he simply has to wait until tomorrow or even the day after to go check the net.

No hurry, no worry.

The worst problem of all with a hoop net is its legality: They are perfectly legal for fishing by properly licensed fishermen.

Finding hoop nets holding crappie is not unusual, and the law is not violated unless the fisherman fails to return the crappie and other game fish to the water when the net is raised.

So wildlife agents must find the net and, if it holds crappie, set up surveillance. They must then see a fisherman raise the net, empty it or take it onboard and prepare to get underway without releasing the captured game fish.

Oddly enough, gill nets were used more often west of the Red River in Avoyelles Parish, while hoop nets were more popular on the east side of the river and in the Saline-Larto area.

That is not to say we didn’t find plenty of both on either side of the river, but one was definitely more common to one side than the other. Whether this was a preference based on tradition or effectiveness for the given area, I don’t know.

Tips on the location of hoop nets are rare, since they are so easy to fish unseen. The local term is “fishing them blind.” Fishermen use a net drag (an iron bar with hooks welded on it and tied to a rope) to find the nets and lift them to the surface.

So do game wardens. We would hang a net drag over the side and slowly motor along in likely spots until we snagged a net and raised it.

If it held crappie, game on.

It is a lot of work that must be combined with a lot of luck.

Another popular crappie catcher is the auto-fisher or yo-yo, which is legal in most places and legal with certain restrictions in others.

It is very effective and has tremendous appeal to those who live or camp on the water’s edge and can make frequent trips to run and re-bait a large number of yo-yos. It is not unusual for a yo-yo fisherman to have 50 or more fishing at once.

On a good night, a lot of crappie may be caught. So many, in fact, that some outlaws make good supplemental incomes by selling the fish.

Which brings us back to the small-scale or local illegal market. Crappie sellers are easy to find if you know where to look.

The earliest example I know of was an old retired fellow who lived on the banks of Little River in Natchitoches Parish near Cloutierville.

He kept a boat tied to his small dock. Mornings and afternoons when the weather was good would find him jigging for crappie among the cypress trees. He would return to his dock and place the fish in a “live bag,” a submerged fish cage tied to a tree limb and hanging in the cool water in the shade of that particular cypress tree.

Everyone in the neighborhood knew where to get a mess of fresh crappie: Just go by this old boy’s place, walk out on the dock, dip out the fish you wanted, pay the man and go home to fry up your fish.

Was it a significant drain on the resource? No. Was he likely to ever get caught? No, and I doubt he was ever even reported to the local agents.

But some illegal operations involve significant numbers of fish and do impact the resource. The most-effective methods wildlife agents have for addressing the problem are:

Vigilance on the water where fish are taken illegally. So keep an eye out for suspicious activity and report it.

Covert operations where undercover agents purchase crappie and other game fish from outlaws, followed by arrest and prosecution of the offender. So report suspected illegal sales as well.

Significant cash rewards are available for information leading to the arrest of offenders. Anonymity is guaranteed.

Got a question? Ask Keith!

If you have a question about wildlife and fisheries enforcement, shoot a note to Keith LaCaze at klacaze15@att.net.