Early inhabitants of the land that would eventually be called Louisiana had to get creative to harvest the abundant wild game.

Bob was excited as he made the predawn drive to his hunting lease. The previous day, he discovered where a deer was bedding on a small hammock near a slough. Within bow range was a leaning post oak tree that made a perfect ambush spot.Bob easily climbed the tree and found a comfortable fork in which to sit. After carefully camouflaging the position with limbs and moss, he returned home full of anticipation for the next morning’s hunt.

Before daylight, Bob was settled in and waiting. The wind was erratic, but he had taken the precaution of spraying on a cover scent before leaving the truck. Since it was in the middle of the rut, he also brought a lightweight doe decoy to set up under his tree.

As first light broke in the swamp, a nice 6-point buck appeared across the slough from the hammock. It nervously watched the decoy for a moment, but then came straight in when Bob gave a soft, reassuring bleat on his grunt call.

A short time later, Bob was back on the ground admiring his kill. All of his careful planning and equipment had worked to perfection.

What Bob did not realize was that nothing he did or used that morning was new. From the powerful bow to the treestand, cover scent and decoy, he was simply employing ancient techniques that Louisiana Indians perfected thousands of years ago.

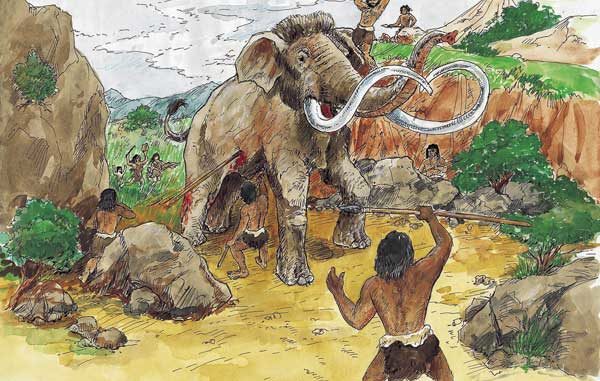

It is not known when Native Americans first arrived in Louisiana, although artifacts have been found dating back 10,000 years. These first inhabitants, known as Paleo Indians, hunted mammoths, mastodons, wild horses and big-horned bison, but little is known of their hunting strategies.

Most likely, they ambushed the huge Ice Age creatures from close range, and repeatedly stuck them with spears tipped with stone points. When construction uncovered a mastodon skeleton in Lafayette a number of years ago, archaeologists found two beautifully made Paleo spear points lying nearby.

When the Ice Age ended approximately 6,000 B.C., Louisiana took on its modern-day appearance, and the mega fauna was replaced by the myriad animals we see today. Paleo Indians had to change too, and they evolved into what are known as the Archaic Indians. Adopting a hunting/gathering strategy, the Archaic Indians survived by hunting, fishing and gathering nuts, shellfish and berries.

The Archaic Indians also adopted a new, more powerful weapon known as the atlatl (AT-lat-ul). This was a short hand-held stick about 18 inches long that was often elaborately carved and decorated. At one end was a grip, while a bone or antler hook was fitted in the other.

The atlatl was a spear-throwing device that fired a long dart resembling an oversized arrow. The back of the dart was fitted onto the hook, and the dart was held in place with the thumb and forefinger.

Using a motion similar to a baseball pitcher, an Indian simply stepped forward and slung the dart with great force over his head. The atlatl was a way to make one’s arm artificially longer and thus get more force behind throwing a spear than could be achieved by hand.

Modern researchers compared a hand-thrown spear with an atlatl dart, and discovered the dart impacted its target with a force several hundred times more powerful than the spear. Tipped with a sharp stone point, atlatl darts were deadly.

Today, atlatl dart points are a common find in Louisiana’s fields and clear cuts. Approximately 2 inches long, with stems or barbs, they are usually mistaken for arrowheads.

The atlatl remained the primary weapon until it was replaced by the bow and arrow around 900 A.D. However, some Indians used both, and Spanish explorers reported fighting Indians on the lower Mississippi River in the 1540s who used atlatls. Some modern hunters are rediscovering the ancient weapon, and Alabama allows its use during the archery deer season.

Archaic Indians mostly used atlatls to hunt deer, but they also harvested virtually every other animal found in the forest. Archaeological sites are filled with the remains of squirrels, mink, turtles, turkeys, rabbits and fish. There are even some elk bones in North Louisiana sites, but it is not clear if the Indians killed them locally or hunted them in Arkansas and brought the meat back to their camp sites.

Around 2,000 B.C., Louisiana Indians entered the Neocultural phase, and slowly began to develop permanent villages and agriculture and evolve into such historic tribes as the Caddo, Choctaw, Natchez and Houma.

While we may never know the exact hunting techniques used by the Paleo and Archaic Indians, French and Spanish explorers encountered the historic Indians and recorded what they saw. No doubt, the hunting tactics they used could be traced back thousands of years.

All historic Indians had great respect for nature. They believed man was a part of the natural environment, just like the animals he hunted, and revered them for dying so they could live. Many Indians said a prayer over their felled prey to thank it for its sacrifice and to ask for forgiveness. The Choctaw even had chiefs who governed deer hunting.

Indian tribes also revered animals for religious reasons. As a result, some avoided certain species they considered sacred. The Houma, for example, did not eat crawfish because it was their tribal totem, and the Koasati (Coushatta) did not eat deer or turkey.

One activity that surprised the explorers was how Indians purposefully manipulated the environment with fire — much like today’s controlled burns in the piney-woods and marsh country. Annual burnings cleared the underbrush, killed ticks and other vermin and created browse for deer.

Everywhere they went, the explorers marveled at how much of Louisiana resembled an open European park. Similar to modern hunters planting food plots to supplement the animals’ nutrition, Indians also planted the seeds of plants deer and other wildlife preferred eating.

The Europeans also came to realize how protective the Indians sometimes were of their hunting grounds. At modern-day Baton Rouge, the Houma and Bayougoula Indians erected a red pole (“baton rouge” in French) to demark their respective hunting lands. A Frenchman noted, “These two nations were so jealous of the hunting in their territories that they would shoot at any of their neighbors whom they caught hunting beyond the limits marked by the red post.”

Some rival hunting club members today could relate to that.

Just like modern people, ancient Indian hunters had to travel some distance from home because they quickly killed all the game around their villages. A “short hunt” entailed heading out a few miles to temporary camps and hunting for a few days.

While women sometimes went along on these short hunts, they were there only to skin the animals and carry the meat back to the village. Hunting was for males only, and a lowly man could greatly increase his standing in the tribe by demonstrating superior hunting skills.

A “long hunt” involved walking many miles to good hunting grounds, and could last for weeks. The elk bones found in North Louisiana archaeological sites may have come from such forays. Usually only the best hunters were allowed to participate in the long hunts. The less-skilled either stayed home or tagged along to do the grunt work of skinning and butchering.

By the time of the Europeans’ arrival, the bow and arrow had largely replaced the atlatl because it was more accurate and easier to use. The Caddo Indians of Northwest Louisiana made some of the best bows in this region.

Years ago, one was discovered in a burial site. Among the bodies in the grave was a huge man who stood about 6 feet tall (most of his contemporaries were just over 5 feet). Lying next to him was a beautifully crafted bow made from bois d’arc (Osage orange).

The bow was 66 inches long, and had a leather grip and recurved tips to give it more power. Radio-carbon dating showed the long bow was 1,000 years old. Three shorter bows were also found in the grave. They lacked the recurved tips, and were between 31 and 36 inches long.

Arrow points (often referred to as “bird points”) were made from flint, antler, bone, cane and even gar scales. They were deadly, and Spanish explorers came to respect the power of the Indian bow. While traveling through the American southeast, one Spanish officer was left pinned to his horse when a cane arrow sliced through his armored leg and saddle.

Using their bows, and later muskets, Louisiana’s Indians hunted a variety of game animals, and used a number of different tactics.

Bears were often targeted while the females were denned up in hollow trees. One Frenchman who witnessed a hunt claimed the Indians first leaned a tree against the den. A man then shinnied up and tossed a lighted torch into the hollow. When the groggy bear backed out of its hole, the Indians shot it with a musket.

“This is a very dangerous kind of hunting,” the Frenchman wrote, “for, although wounded sometimes by three or four shots from a gun, this animal still will not fail to charge the first person he meets, and with one single blow of tooth and claw, he will tear you to pieces instantly. There are bears as big as coach horses and so strong that they can very easily break a tree as big as one’s height.”

Another method of taking bear involved setting a deadfall trap with a heavy log to crush the animal.

Alligators were another dangerous quarry. They were killed by ramming a sharpened sapling down their open mouth into the gullet. The Indians then flipped the gator over to expose his soft underbelly and dispatched it with a spear.

Buffalo were a favorite pursuit in the prairie country. French accounts indicate the Indians either quietly stalked the buffalo or used fire to drive them into ambush points. One explorer explained the latter method: “When the Savages discover a great Number of those Beasts together, they likewise assemble their whole Tribe to encompass the Bulls, and then set on fire the dry Herbs about them, except in some places, which they leave free; and therein lay themselves in Ambuscade. The Bulls seeing the Flame round them, run away through those Passages where they see no Fire; and there all into the Hands of the Savages, who by these Means kill sometimes above sixscore a day.”

Many different strategies were used to hunt small game and fowl. Snares snagged coons and rabbits, and blowguns dispatched squirrels and birds. At night, Indians gathered at known passenger pigeon roosts armed with torches and long poles. The bright lights blinded the birds, and they sat passively while the people knocked them from the branches with their poles.

An ingenious trap was used to gather quail. First, a downward sloping runway was dug into the ground into a deep hole. Sticks were then placed over the entire trap, and corn was used to draw the birds down the runway into the hole.

After eating the corn, the quail would try to fly away but were trapped by the overlying sticks. They then sat quietly until the Indians came back to retrieve them.

Turkeys were lured into bow range with calls made from a turkey wing bone, and magic was utilized in all forms of hunting. Each tribe had a shaman who knew the precise medicine, chant or prayer to ensure a good hunt.

One puzzling discovery made by archaeologists is that ancient Louisiana Indians apparently did not depend much on ducks or geese for food. For example, the Tchefuncte Indians, who flourished around the time of Christ, lived along streams and in other wet environments, but duck remains are hardly ever found in their sites.

The historic Indians did go after waterfowl on occasion and utilized a number of tactics. Bolas may have been used to tangle up rising flocks of ducks, and there is some evidence nets were stretched across narrow sloughs where ducks were feeding on acorns. Other Indians then jumped the ducks and flushed them into the nets, where they were clubbed to death.

When hunting ducks and geese with bows and guns, decoys were made from gourds or by stuffing the skins of dead birds. Ibis (gros bec) were hunted by using a wounded bird as a decoy.

One traditional goose hunting tactic only came to light in the 1960s when an old Indian man on Catahoula Lake actually caught some wild geese by hand. Before daylight, he waded out in shallow water where he knew geese congregated and sat down with only his head sticking above water.

The man told astonished wildlife officials that geese were curious creatures, and if you sat absolutely still long enough, the birds would eventually check you out. He then grabbed them by the legs under the water. The old Indian was nonchalant about it all, but did admit the wait became difficult when the water began to freeze around him.

Of all the game Indians hunted, none got more attention from the explorers than deer. Deer provided the most meat for the effort, and all Indians exploited them year round.

Indian hunters often looked for bedding areas, and then stayed there all night to bushwhack them in the morning. They also hid out in trees, camouflaging themselves with leafy branches.

Sometimes standers were placed at strategic escape points on the prairies and marshes, and the grass was set on fire to push the deer toward them. Drives were also made through known bedding thickets to run deer to standers. Some evidence indicates dogs may also have been used in deer hunting, but the details are unknown.

For the Natchez, deer hunting was sometimes a communal effort. The French claimed the Indians would find a deer and then form a semi-circle around it with as many as 100 men who chased the deer from side to side until it finally fell from exhaustion and was killed. This deer chase was said to have been as much a sport for entertainment as a way to gather food.

Although it defies belief, the French claimed the Attakapas Indians, who inhabited the prairies and marsh country of Southwest Louisiana, used relays to run deer to exhaustion.

Indians also knew the usefulness of deer decoys and often caped out the head and shoulders of a kill, stretched it on a cane hoop, and cured it with smoke. The Natchitoches were said to have used capes with the antlers attached.

When hunting, the Indian either wore the decoy or carried it in one hand and used mimicking motions and calls to draw his quarry near. A buck’s grunt was used during the rut and a doe’s bleat in the spring.

Indians even used cover scents. Before going out, hunters immersed themselves in the smoke of a red oak fire. Just as today, woods fires were common across Louisiana hundreds of years ago, and Indian hunters knew the natural smell of smoke would not alarm their prey.

So the next time you stuff the grunt call in your pocket or grab the climbing stand to get high in the timber, stop for a moment and give tribute to Louisiana’s ancient Indian hunters.

The more things change, the more they stay the same.