In Louisiana, there are few family traditions as strong as hunting. From one generation to another, a love for the land and the animals who live there is passed down. It is tradition and honor.

Each fall this rite of passage is played out across Louisiana, on farms, family land or leases, and for each family the events become memories that will no doubt one day be shared with the next generation. For one northeast Louisiana family however, three generations have now benefited from the creation of the Tensas River National Refuge (TRNR).

By the early to mid 1970’s, much of the Louisiana Delta was being cleared to make room for farming. Madison, Tensas and Franklin parishes saw hundreds of thousands of acres fall to the saw blade and bulldozer, effectively eliminating dozens of large hunting clubs, leaving many families without a place to hunt. For Jimmy Griffing who grew up in Gilbert, the destruction of his family’s hunting club was a sad time.

“Lots of that timber didn’t even get sent to a mill. They just pushed it over with bulldozers into piles and set it ablaze. It seemed like a smokey haze hung in the air for months while the work progressed,” he said. “Slowly we came to realize that our hunting club, Three Buck Bayou, would never be the same. To see such a paradise destroyed made me truly appreciate the Tensas River National Refuge and Big Lake Management Area.”

Giving it a try

In 1987, after several years of trying to find a place to hunt, Griffing began hearing stories of large bucks being taken on the TRNR, and with a young son coming of age to hunt, Griffing decided to give the public land a try.

“Up until the first day I stepped foot on the Tensas Refuge, I’d never hunted public land of any kind,” he said.

Griffing recalled the fateful day when he first discovered just how good the deer hunting was.

“I’d walked almost two miles with my stand and bow before I came to a large oak dropping acorns,” he said. “It was close to 4 p.m. by the time I got up a tree and settled in. Fifteen minutes later I was drawing on my first public land buck.

“I was on vacation and decided to hunt the next several days. Each day I saw lots of deer and one large 10-point that I decided to focus on. On my last day of vacation, I was fortunate enough to arrow him. I’d seen all I needed to. I knew this was a place where I could teach my son how to hunt.”

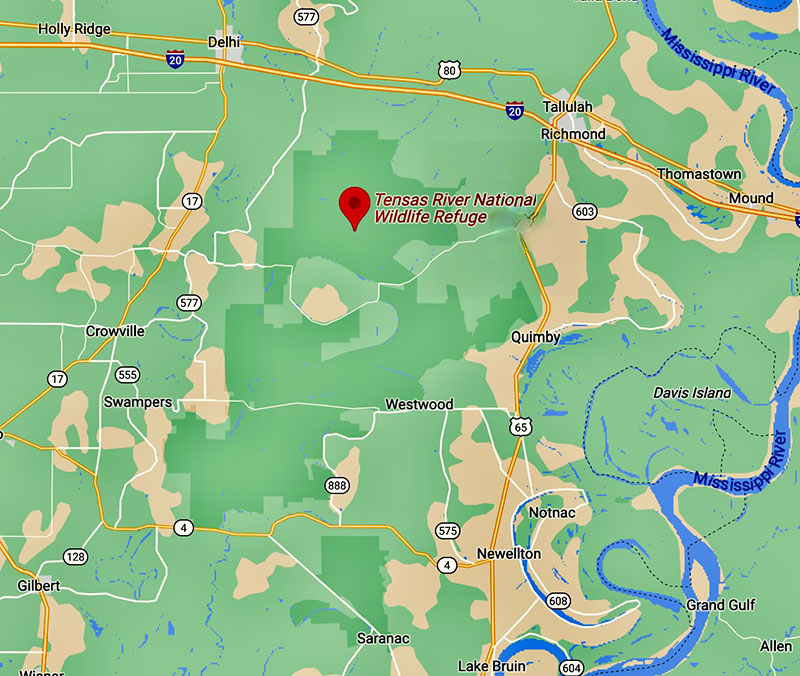

The Tensas River National Refuge was established in 1980 to preserve one of the largest privately owned tracts of bottomland hardwoods remaining in the Mississippi Delta. At just under 75,000 acres, it contains miles of timber, waterways, wildlife and opportunity for hunters willing to work a little in order to access areas off the beaten path. According to Griffing, being successful on the Tensas requires some extra effort.

“You’ve got to be willing to walk, to get away from folks,” he sad. “If you can do that, you’ll see deer.”

Father and son

Father and son

In 1981, one year after the formation of the Tensas River National Refuge, Jimmy and his wife welcomed their first son, Jarred. Griffing wouldn’t wait long to begin taking his son onto the refuge, and by the time the boy was 8, he was climbing a nearby tree, with his own bow in hand.

“I’d find two trees kinda close and help him get started climbing the tree, Griffing said. “Then I would help him with his bow, make sure he had his safety belt on and climb up a tree nearby.”

It turned out Jarred was a natural, and with Griffing watching on, he successfully arrowed his first deer on the refuge during that first season of bowhunting with his Dad.

One of the many things the elder Griffing liked about the refuge was the fact that Jarred was forced to learn skills that are often overlooked today.

“By the time he was a teenager he knew the different oak species and when they would drop their acorns,” Griffing said. “He learned to read sign and find trails in places that were most often not easy to decipher.”

For the younger Griffing, the refuge was one giant playground.

“I absolutely loved everything about it,” Jarred said. “We deer and squirrel hunted, shot our 22’s, learned to build a fire and made friendships that I still have to this day.”

One skill that Jarred learned as a boy was to properly read a compass. According to Jarred, his Dad taught him how to properly read a compass.

“Back then there wasn’t any GPS, and if you’ve ever been on the refuge, you know most of the habitat looks very similar,” the younger Griffing said. “You throw in the amount of water it holds during the winter and if you couldn’t read a compass, you may find yourself in trouble.”

According to Jimmy Griffing, the compass played a huge role in their success.

“The compass allowed us to really strike out and not worry about roads, trails, flagging tape or bright eyes,” he said. “We were able to get away from the vast majority of other hunters.”

Eventually, that compass would play a vital role in Jarred’s life when he was only 13 years old.

Tragedy strikes

One afternoon while shooting wood ducks, Jarred witnessed a close family friend lose his life to an errant rifle shot.

That afternoon they were on some private ground, shooting wood ducks on the edge of a large agricultural field. Todd Roberts, a teacher at Crowville High School, was a mentor to Jarred, another person in addition to his father who had taught him much about hunting the refuge.

“It happened so quickly, initially I wasn’t sure what exactly was going on,” he said. “Todd had gone to retrieve a duck and was walking back to our setup when he collapsed. I’d heard the rifle shot and when I realized Todd was hurt, I immediately took a compass reading from the direction I heard the shot come from.”

Later on, the Sheriff would tell Jimmy that Jarred’s compass reading had taken them right to the hunter who had fired the fatal shot.

In 2008, the tradition began to grow even deeper. Jarred and his wife Paula would welcome their first son, Gavin, to the family, followed by Parker in 2013. And with the arrival of the boys, the lessons learned on the refuge would begin again. Just like his father did with him, Jarred would start both boys out hunting at a young age, with much of that hunting taking place on the Tensas River National Refuge.

“We don’t do as much deer hunting on the refuge anymore,” Jarred said. “With the advent of GPS, it became too difficult to get away from the crowds. However, both my boys have killed turkeys on there and we plan on continuing to chase them during the spring season.”

The youngest boy, Parker, is a gifted baseball player who recently walked away from one of the most successful 9-year-old teams in Louisiana.

“Yep, it was just tearing him up knowing that his older brother was turkey hunting while he was at the ballpark,” Jarred said.

Parker decided a little less baseball would be good for his soul, and with a grandfather like Jimmy, who takes him fishing almost everyday, who can blame him.

Final thoughts

For Jimmy Griffing, now 67, the lessons he taught his son have now been passed down to his grandsons.

“It’s just who we are,” he said. “We’re hunters and the fact that I was able to share my love of hunting with my son has meant so much to me. Now that I’m retired, I love the fact the boys are always ready to go hunting or fishing with me. Heck, even my daughter in law, Paula hunts with us.”

Thankfully for so many of us that do love to hunt, love the outdoors and love the tradition of families in the woods, a group of men and women understood the need to preserve so much of the Mississippi Delta bottomland.

“My son and grandsons are all very good hunters, and the fact that they grew up hunting on the refuge has played a big role in their success,” Griffing said.