This avid sac-a-lait fisherman is spending his retirement catching the best-tasting fish that swims. Here’s how he does it.

As David Pizzolato slid another sac-a-lait into his cooler, he couldn’t help but pine for the future of his favorite kind of fishing.

“You know, we’ve got a big problem with sac-a-lait fishing,” he bemoaned while flipping his black shad Bass Assassin Tiny Shad back between the forked limbs of a fallen cypress tree. “We don’t have enough young anglers getting into it.”

I thought about that for a moment, and reflected on my own evolution as an angler. Sac-a-lait didn’t even enter the picture until just recently — about the time I turned 40. Before that, it was the highly polished, metal-flake world of bass fishing.

I chose my words carefully.

“I think,” I tiptoed, “that anglers eventually migrate to sac-a-lait fishing after the glamour eventually wears off the bass fishing.”

Pizzolato turned and sat down on the lean-to seat jutting high from the front deck of his Xpress boat.

“Migrate, huh?” he responded. “Don’t think I’ve ever heard it put like that before.”

“Migrate, evolve — whatever you want to call it,” I continued. “I think sac-a-lait are at the end of the line. Seems to me the older I get the more I enjoy catching them.”

“You telling me I’m at the end of the line?” the Greenwell Springs resident rebutted while lifting his Louisiana Fish Fry Products cap off his head full of gray hair. “Well, if that’s the case, there’s nowhere I would rather be waiting in line than Belle River.”

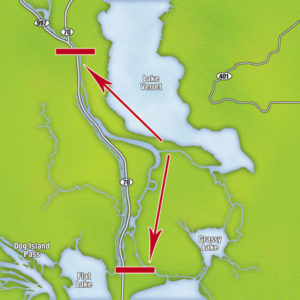

Earlier that morning, my son Matthew and I had followed Pizzolato and his grandson Jonathan from the Spillway Sportsman on Highway 1 just south of Baton Rouge all the way to Adams Landing just north of Stephensville.

Earlier that morning, my son Matthew and I had followed Pizzolato and his grandson Jonathan from the Spillway Sportsman on Highway 1 just south of Baton Rouge all the way to Adams Landing just north of Stephensville.

This is Pizzolato’s typical trek two days a week as the twice-retired angler, once from the U.S. Army and once from being a manager in the produce business, lives out his golden years chasing sac-a-lait.

Before Pizzolato could get his boat on plane, he asked my son if he knew who Clint Eastwood was.

“A friend of my dad’s?” my son wondered.

“He’s everybody’s friend, but listen,” said Pizzolato. “He has a famous saying. Do you know what it is? Make my day.

“Well, I’m going to make your day, buddy, right here on the Belle River.”

We soon idled up to a lone cypress tree, if a cypress tree can somehow be alone among thousands of other cypress trees. There was definitely something different about it, though, and Pizzolato explained that we were going to begin by tightlining opening night and black shad jigs made by Bass Assassin.

A freshening wind blew straight up the river as we began dunking our fake baitfish down beside a hidden cypress tree just barely visible beneath the surface and positioned parallel to the bank. The base of the sunken log met the base of the lone cypress tree that marked the spot.

Within just a couple of minutes, two nice sac-a-lait were eternally resting on a bed of ice. Always the observant angler, Pizzolato began to compare this day with his last trip just a few days before.

“The water temperature is four degrees warmer today than when we were here Sunday,” he noticed. “And we were fighting a stronger wind — a southeast wind. This is a predominant south wind. The fish are right on the cover, though, right where they should be. Looks like the pattern today will be the same as it was Sunday.”

Pizzolato cut his words short as he noticed that my son had a fish on without realizing it. The large sac-a-lait protested profusely upon Pizzolato’s direction to set the hook, but it was no match for the big net that swooped down to pick it up.

Our next submerged cypress log gave up four keeper sac-a-lait and one throwback. All the keeper fish were about 10 or 11 inches, and Pizzolato says he’s found that these sac-a-lait tend to school up by size.

“Some of these spots we’re fishing will hold one, and others may hold 15,” he said. “That’s why my fishing down here turns mostly into hitting maybe 10 spots going one way on the river and hitting them again as I make my way back to the ramp. It’s mainly a lot of downed trees, but there are some piers down here where the sac-a-lait really gang up.”

As we fished our third spot, the first one that left us empty-handed, Pizzolato began instructing my son about how to detect a bite. The depth finder said 8 feet out the front of the boat, and he dropped his jig down on top of the cypress log on purpose.

“See the line curl up,” he asked. “The water is 8 feet, but that line started curling up when the bait got down about 4 feet. When you see your line curl up, your bait has either landed on top of something or a fish has it — it’s stopped falling. If it’s the tree and not a fish, just jig it off the side. They’ll hit it.”

As we continued moving from spot to spot, Pizzolato pointed out that there wasn’t anything really secretive about the spots we were fishing. Each spot we hit stood out like a sore thumb that would attract just about anybody passing by.

However, if there were anything secretive about the spots we fished, Pizzolato said it would have to be that there is a lot more structure under the water than what you can see sticking out of the water.

“Look at that cypress tree over there,” he pointed out. “Say it falls into the water. Look at the way all those branches are coming off the tree. So over a few years of fishing that tree after it falls, you’ll learn where each of those limbs stick out from the tree trunk. The only way to figure it out is to let your bait tell you the rest of the story.”

And just about that same time, Pizzolato’s bait told him that there were some bigger sac-a-lait holding in the same 4- to 6-foot zone we had been fishing. At first, he didn’t believe it to be a sac-a-lait because it was pulling so hard, but he added that if it was one that he was going to quickly need the net.

However, just like the earlier spots we had fished, our third spot only gave up a couple of fish. Pizzolato couldn’t help but think about the piers on down the river a little bit where he and his grandson had slammed some slabs just a few days earlier.

The two poked in and out of a few piers to try to figure out which one had been so productive for them, and grandson Jonathan eventually spotted the one they were looking for.

“See the shade under there?” Pizzolato asked. “That’s where the fish are going to be under these piers. Some of them have some debris — brushpiles and stuff — under them, but the fish are more attracted to the shade. When the shade moves as the sun moves across the sky, the fish are going to move with it.”

We all started flipping black/sliver Bass Pro Crappie Beavers into the shady spots under the pier, but the elder Pizzolato had somehow found himself in just the perfect spot — the rewards for running the trolling motor.

Pizzolato explained that fishing these Belle River piers that are so low to the water presents some challenges that anglers have to take into account if they want to successfully drag out the fish without tearing up their rods. His 10-foot pole was all the way under the pier, which didn’t leave him much room to set the hook.

“You’ve got to have an avenue of escape,” he explained. “See the way I’m fishing this shady corner. There’s no way I can pull up on my rod without slamming it into the bottom of this pier, but I have a little opening to my left where I can swing my rod when I get a bite.”

After landing several big sac-a-lait from under this single pier, Pizzolato thought it might be time for a break, and crawfish boudin sounded a whole lot better than my bologna sandwich. We wound up at Gros’ Marina on the banks of Four Mile Bayou just south of Lake Verret.

Pizzolato took time at this tranquil setting to explain a little bit more about why the Belle River area between Adams Landing and Stephensville is so productive and how he makes the most of his time on the water.

“Today we only fished between Adams Landing and Bayou Magazille,” he began. “We hit about seven or eight spots going down the river, and we’re going to hit them again going back up the river. Notice we didn’t spend a lot of time on each spot; we stayed only as long as the fish were biting.

“I give each spot maybe five to 10 minutes. If they’re there, you’ll know in that amount of time. There’s no way I’m going to be sitting on the same spot 30 minutes later to see if they turn on. When it’s right down here, I’ve had days when we’ve caught over 125 sac-a-lait.”

We let our lunches settle as we fished our way back to Adams Landing. A few of the spots gave up some more sac-a-lait just as Pizzolato had expected they would.

For Pizzolato, the migration to sac-a-lait fishing ended on July 4, 1987, because he has fished only for them ever since.

And if our day on the Belle River was any indication of just how fun sac-a-lait fishing is even when they aren’t completely turned on, I can’t wait for May, 25, 2026, the day my retirement begins and my migration is complete.