Often taken for granted, oil rigs are boom to fishing and economy

Editor’s Note: Veteran Louisiana angler and writer Humberto Fontova has taken his case about the benefits of offshore oil rigs to the nation. He shares his story, views and experiences with Louisiana Sportsman readers.

“So, who you gonna believe?” smirked a dripping Pelayo while reaching for his friend’s Zach’s speargun. “Me? Or your eyes?”

We were helping our Florida friend Zach onto the 25 footer’s fantail after his first Louisiana rig dive — and the famous quip from Groucho Marx seemed ideal.

“Whoo!. . . whoo!” Zach gasped while quickly pulling himself aboard, wiping his face, and jerking the writhing mangrove off his speargun shaft. “Who to believe?” he wheezed. “Who? Well both!” he finally snorted.

“I ain’t never. I ain’t NEVAH!…I ain’t NEVAH seen so many fish! And not nearly as many BIG ones! Most of these mangroves could easily SWALLOW the ones I catch in Florida!” he said.

Two weeks earlier Zach had been scoffing. He’d heard about Louisiana’s offshore fish bounty on Fox & Friends from an interview aired on Fox News with your humble servant here. He promptly called us to (good-naturedly) scoff. By the way, he wasn’t the only scoffer. The hate e-mail is still coming!

Seeing is believing

Zach’s scoffing ended after five minutes under an oil platform barely eight miles from Belle Pass. Happens every time we take an “experienced” scuba diver or snorkeler on his first dive to a Louisiana offshore oil platform. Never fails.

Now, when we take our out of town friends and relatives rig fishing, we hear almost the identical gasps — except “caught” replaces “seen.”

But prior the eyewitness reactions above, most of what we heard from our future rig fishing and diving guests were scoffs and harrumphs — especially from those with a greenie (“environmentalist”) streak, like Zach. I mean, here we are touting a marine habitat created by the greenie’s major villain, a perceived combination of Snidley-Whiplash/Darth-Vader, known as “Big Oil.”

Heck, on the ride down to Fourchon, Zach had been regaling us with stories about how some of his hot-shot fishing guide chums in the Florida Keys, where drilling is strictly forbidden, had put him on “TWO Jack Crevalle in ONE morning! And that was along with “three mangrove snapper!”

Heck, on the ride down to Fourchon, Zach had been regaling us with stories about how some of his hot-shot fishing guide chums in the Florida Keys, where drilling is strictly forbidden, had put him on “TWO Jack Crevalle in ONE morning! And that was along with “three mangrove snapper!”

“GET OUTTA HERE!” a wide-eyed Pelayo mock-gasped. “You can’t mean it dude! WOW! Sounds like one helluva fishing trip! You Floridians are obviously spoiled with all that pristine, oil-platform-free fishing in Florida!” then Pelayo lowered his voice a bit and cocked his head.

“Kinda makes me wonder why we see all those Florida license plates in our marina parking lots? Hummmm?”

But enough with the anecdotes. After all, Louisiana’s fishing guides probably hear the same weekly from their out-of-state clients. Instead let’s “follow-the-science” as the greenies themselves love to scold the rest of us on “climate-change,” “carbon footprints,” blah…blah…blah.

Difference is, the following isn’t bogus dreamland science. Here are some of the facts I shared on Fox that caused such a stir with environmentalists, most of whom have never seen an oil rig.

Amazing fish densities

To wit: a 2006 study conducted by LSU’s Coastal Marine Institute (in conjunction with the U.S. Dept. of Interior) found, “Offshore oil platforms support fish densities from 10 to 100 times the densities of adjacent sand and mud bottoms.”

Another study by Dr Bob Shipp, Professor Emeritus at the Marine Sciences Department of the University of South Alabama and long-time vice-chair of the Gulf of Mexico Fisheries Management Council, found that “massive areas of the northwestern Gulf of Mexico were essentially empty of red snapper stocks for the first hundred years of the fishery. Subsequently, areas in the western Gulf have become the major source of red snapper, concurrent with the appearance of thousands of petroleum platforms.”

Another report by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Minerals, a division of the U.S. Dept. of the Interior, boasted “fish densities are 20 to 50 times higher at oil and gas platforms than in nearby Gulf water, and each platform seasonally serves as critical habitat for 10 to 20 thousand fishes.”

”Ten to thirty thousand adult fish live around an oil production platform in area half the size of a football field,” revealed a study by Dr. Charles Wilson of LSU’s Dept. of Oceanography and Coastal Science.

“The fish biomass around an offshore oil platform is 10 times greater per unit area than for natural coral reefs, such as in the Flower Gardens Federal (Dept. of the Interior) Coastal Sanctuary,” Dr Wilson’s study also found.

Yet another study by LSU’s Sea Grant college showed that 70 percent of Louisiana’s offshore fishing trips target these platforms. The same study showed 50 times more marine life around an oil production platform than in the surrounding Gulf bottoms.

An environmental study (by apparently honest scientists) revealed that urban runoff and treated sewage dump 12 times the amount of petroleum into the Gulf of Mexico than those thousands of oil production platforms. And oil seeping naturally through the ocean floor into the Gulf, where it dissipates over time, accounts for seven times the amount spilled by rigs and pipelines in any given year.

Flower garden reefs

The Flower Garden coral reefs lie off the Louisiana-Texas border. Unlike any of the Florida Keys reefs, they’re surrounded by dozens of offshore oil platforms. Some of these have been pumping away for over 60 years. Yet according to G.P. Schmahl, a federal biologist who worked for decades in both places, “The Flower Gardens are much healthier, more pristine than anything in the Florida Keys. It was a surprise to me,” he admits. “And I think it’s a surprise to most people.”

“A key measure of the health of a reef is the amount of area taken up by coral,” according to a report by Steve Gittings, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s science coordinator for marine sanctuaries. “Louisiana’s Flower Garden boasts nearly 50 percent coral cover. In the Florida Keys it can run as little as 5 percent.”

These are stories you will never hear in the mainstream media.

Mark Ferrulo, a Florida “environmental activist” uses the very example of Louisiana for his anti-offshore drilling campaign, calling Louisiana’s coast “the nation’s toilet.” Well, Mr. Ferrulo must not know that Florida’s fishing fleet must love fishing in toilets, and her restaurants serving a lot of what’s in them. Back before snapper were highly regulated, many of the red snapper you ate in Florida restaurants were caught around Louisiana’s oil platforms. We used to see the Florida-registered boats tied up to them constantly. Sometimes us locals could barely squeeze in.

In brief, “villainous” Big Oil produces marine life at rates that shames the greenies’ wondrous Earth Goddess Gaia.

That this proliferation of seafood in the Gulf of Mexico came because — rather than in spite — of the oil production rattled many environmental cages and provoked a legion of scoffers.

Bug-eyed again

Bug-eyed again

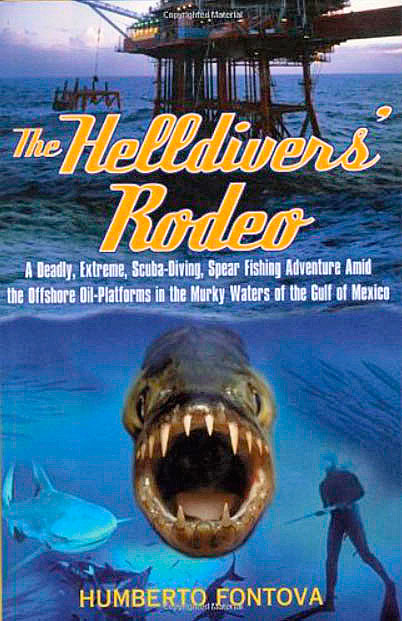

Amongst the scoffers were some Travel Channel producers, fashionably greenish in their views. They read these claims a few years ago in a book by your humble servant titled, “The Helldiver’s Rodeo” — that Publishers Weekly hailed as “highly-entertaining!” (Ted Nugent’s blurb certainly didn’t help against their scoffing!)

The book describes an undersea panorama that (if true) could make an interesting show for the network, they concluded, while still scoffing. They scoffed as we rode in from the airport. They scoffed over raw oysters, grilled redfish and seafood gumbo that night. More scoffing through the Hurricanes at Pat O’Brien’s. They scoffed even while suiting up in dive gear and checking the cameras as we tied up to an oil platform 20 miles in the Gulf off the southeast Louisiana coast.

But they came out of the water bug-eyed and indeed produced and broadcast a Travel Channel program showcasing a panorama that turned on its head every environmental superstition against offshore oil drilling. Schools of fish filled the water column from top to bottom — from 6-inch blennies to 12-foot sharks. Fish by the thousands. Fish by the ton.

The cameras were going crazy. Do I focus on the shoals of barracuda? Or that cloud of jacks? On the immense schools of snapper below, or on the fleet of tarpon above? How ’bout this — whoa — hammerhead!

We had some close-ups, too, of coral and sponges, the very things disappearing off Florida’s pampered reefs — a state that bans offshore oil drilling. Off Louisiana, they sprout in colorful profusion from the huge steel beams — acres of them. You’d never guess this was part of that unsightly structure above. The panorama of marine life around an offshore oil platform staggers anyone who puts on goggles and takes a peek, even the most worldly scuba divers.

“But what about the BP oil spill, Humberto?” comes the greenie retort. “Seems you’re very conveniently overlooking that disaster!”

In fact, the best demolition of environmentalist bull-dinky on the BP oil spill was compiled and presented right here at Louisiana Sportsman, barely a year after the spill itself and the barrage of doom-saying greenie prognostications. The thorough — and thoroughly documented — demolition was by retired professor of fisheries and writer, Jerald Horst, from whose articles I borrow much of the following quotes and data.

“The damaging effects of the massive oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico will be felt all the way to Europe and the Arctic!” a “top scientist” told a congressional panel shortly after the spill, reported CNN.

In fact, the damaging effects were hardly visible in Louisiana a few months later, according to Marine scientist and former Louisiana State University professor Ivor van Heerden, who also worked as a BP spill-response contractor and spent countless days inspecting the Louisiana coast. He found less than 1 square mile of coastal marsh had been severely oiled, mostly around Timbalier Bay. That’s out of 5,300 square miles of Louisiana coastal marsh and swamp, by the way.

“There’s just no data to suggest this is an environmental disaster,” said Professor Van Heerden. “I have no interest in making BP look good — I think they lied about the size of the spill — but we’re not seeing catastrophic impacts. There’s a lot of hype, but no evidence to justify it.”

These observations came on the very heels of the spill — a mere three months afterward, making them all the more blasphemous at the time. Within one short year they’d been completely vindicated.

Bounced back quickly

By July 2010, the “severely oiled” areas were already bouncing back.

“Van Heerden’s assessment team showed me around Casse-tete Island in Timbalier Bay,” Time magazine’s Michael Grunwald wrote back then, “where new shoots of Spartina [marsh] grasses were sprouting in oiled marshes and new leaves were already growing on the first black mangroves I’ve ever seen that were actually black.”

The reasons this “disaster” fizzled out are many, and were apparent to non-hack scientists from the get-go.

“People don’t comprehend how so much oil could break down in such a short time period,” explained LuAnn White, a toxicologist with the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine who also served as director of the Center for Applied Environmental Health. “But we have natural oil seeps in the Gulf, and over 200 genera of microbes that break down oil already exist there.”

“It cannot be repeated often enough,” said Horst. “Crude oil is a natural substance; it’s biodegradable. It’s a feast for microbes. And these consumed most of it from the BP spill.”

The horrid black goo that leaked into the Gulf of Mexico from the BP spill was certainly toxic — but so are broccoli, beer and salt. It all depends on the dosage. In fact, that horrid black goo has spilled naturally into the Gulf for millenniums — at the rate of two Exxon Valdez spills annually.

Nothing normally soothes the savage beast of an environmentalist like the notion of a substance being “biodegradable.” Indeed, the term “environmentally friendly” has become almost its synonym. Well, crude oil is about as biodegradable as substances come, especially when spewed into warm, microbe-filled waters like those in the Gulf of Mexico. Hence the stratospheric dunce caps crowning so many “environmentalist” heads a mere year after “the worst environmental disaster in U.S. history.”

“Ah,” you ask, “but what about that poisonous chemical used as a dispersant for the oil?”

You probably ingested traces of this poisonous chemical compound with last night’s dinner, and other traces probably coat your pots, pans, cups, spoons and forks right now. Some people call the dispersant Corexit 9500 — and some call it soap. Essentially, it was Dawn dishwashing detergent.

“Dispersants are not very toxic,” explains Robert Dickey, director of the Food and Drug Administration’s Gulf Coast Seafood Laboratory. “They are detergents and solvents, and they become rapidly diluted. One square mile of seawater one foot deep is 200 million gallons. We added 1.8 million gallons in the whole Gulf.”

Point is: You add much higher concentration to your kitchen sink to make your dishes “safe” for your family.

Safe seafood

After the spill, the FDA’s Gulf Coast Seafood Laboratory, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Seafood Inspection Laboratory, the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals and similar agencies from neighboring Gulf Coast states have methodically and repeatedly tested Gulf seafood for cancer-causing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH).

“Not a single sample (for oil or dispersant) has come anywhere close to levels of concern,” reported Olivia Watkins, executive media adviser for the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries.

“All of the samples have been 100-fold or even 1,000-fold below all of these levels,” reported Mr. Dickey, the seafood laboratory director. “Nothing ever came close to these levels.”

As mentioned, an earlier study by Dr. Charles Wilson of LSU’s Department of Oceanography and Coastal Science put the scientific touche’ to something fishermen had known for decades: The fish biomass around an offshore oil platform is 10 times greater per unit area than for natural coral reefs. The science is settled.

Fontova makes his case on national TV

Fontova makes his case on national TV

Even though he only had a few minutes, Humberto not only made his point about offshore drilling and its benefit, he did it passionately in an interview with Fox News that aired on July 17, 2022.

You can still view the interview online at: www.louisianasportsman.com/fishing/offshore-fishing/fontova-argues-offshore-drilling-produces-oil-and-fish/