Setting up trail cams in the right spots will put smiles on the faces of even the most seasoned deer hunters.

Boaters and anglers often assume that any old sonar unit will find the bottom and track it reliably as they cruise and fish, but that’s not necessarily true. Units with higher operating frequencies help a unit show better screen detail and work well over a wide range of boat speeds. Lower frequencies penetrate to greater depths and offer much wider transducer cone angles, but they deliver poorer screen detail, and some don’t work at all above trolling speed.

More 200 kHz fish finders are sold for freshwater use than units using any other frequency. This frequency has worked its way to the top in popularity because it offers the best overall combination of screen detail, depth reach and high-speed performance.

Dual-frequency fish finders using both 200 kHz and 50 kHz are the most popular with saltwater users. This combination of frequencies gives them the extra detail of 200 kHz when fishing inshore or for suspended fish offshore, yet it also provides the extra depth penetration of 50 kHz when they venture out into blue water offshore. These units are designed for deep-water use, and come with transducers that focus their 200 kHz sound transmissions into a narrow 10- to 12-degree beam that helps the high frequency work more effectively at greater depths than the 20-degree beams common to transducers usually shipped with freshwater units.

On the other hand, the 10-degree beam often doesn’t cover an area as wide as the average boat in the shallower depths usually fished in fresh water.

Dual-frequency fish finders that use 200 kHz and 80-83 kHz are gaining popularity. They often come with transducers that generate a 20-degree, 200 kHz beam better suited for freshwater and shallower saltwater use.

Their low frequency is high enough to offer better detail than 50 kHz, and works better at higher boat speeds. This combination is well suited for inland and coastal fishing, and the more powerful models using it can handle most offshore fishing.

Some models include a dual-frequency display mode that combines echoes from both the high and low frequencies into a single, full-screen picture. The “dual” mode on traditional 200/50 kHz units usually consists of two separate windows side by side on the display, one showing a high-frequency picture and the other a low-frequency picture.

The highest fish finder frequency in widespread use is 455 kHz. Theoretically, it can show better screen detail than 200 kHz in a unit having enough transmitter/sophistication and screen resolution to do it.

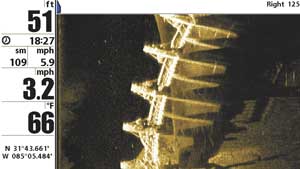

The best example I’ve seen of this frequency’s potential for showing detail is in the side-imaging feature found in several of Humminbird’s newer models. The company’s web site includes an impressive collection of captured side-imaging screen pictures. The extraordinary detail in images of baitfish, sunken boats, the floodgates on a submerged dam and other screen pictures rivals or betters anything I’ve seen recorded by commercial side-scanning equipment.

Perhaps the most notable disadvantage to using higher frequencies is power related. The higher the operating frequency the more transmitter power it takes to reach a given depth. Almost any unit performs well down to 100 feet or so, but power can become an issue for those who want detailed screen pictures at depths of 150-200 feet or more.

Fish finder efficiency varies with bottom composition and water conditions, so comparing notes with others who cruise and fish your favorite waters can also help you pick the best sonar operating frequency.