Despite the hell the feral hog is receiving, it still manages to survive

Back in July our nation celebrated its 238th birthday. No doubt many of you celebrated Independence Day watching a traditional fireworks display; you saw the rocket’s red glare and the bombs bursting in air, and hopefully avoided the popping of a firecracker in your hand.

Our nation is relatively young when compared to the age of our European neighbors. And, while we did experience a Civil War that could have been really challenging for our survival, we are still One Nation that, according to our coins, trusts in God.

While we were watching fireworks, the old feral hog was hunkered down somewhere celebrating 475 years of survival in the U.S. of A.

I say it was hunkered down because today the feral hog is being pursued day and night, on the ground and from helicopter air assaults. It is being chased by men with dogs, trapped with all sorts of traps (some that can be tripped via the phone or computer) and now there is research going on to discover if the hog can be poisoned.

But despite these efforts to obliterate the feral hog, it still manages to survive, and because of this I tip my hat to this survivor of the fittest.

So much has been written about this critter that most of you should know the history of the feral hog. It came to the U.S. on a boat from Cuba as part of the expedition of Hernando de Soto in 1539.

De Soto was on a mission to explore the southern region of North America known as La Florida. It is interesting that the history books report that de Soto brought a herd of pigs with him as emergency food. Emergency food? I guess those poor Spaniards did not know how to cook pork.

But, indeed, it was a good choice for food. Here is an animal that can live off the land, eating what it roots up and does not need to have grain supplied to it on a daily basis. No doubt those pigs thought they were in hog heaven when they discovered an abundance of hardwood mast in this new land.

Hogs’ high reproductive rate ensured a regular supply of pork for the kitchen. In those days there were a few predators such as bears, wolves and cougars that would have preyed on the pigs, but certainly did not eliminate them.

And so de Soto marched across the southeast United States until he came to the mighty Mississippi, which would eventually be the burial site for this Spanish explorer. He found no gold, but he did discover the Mississippi River, and he does get credit for introducing pigs into the southeast United States, from Florida to Arkansas.

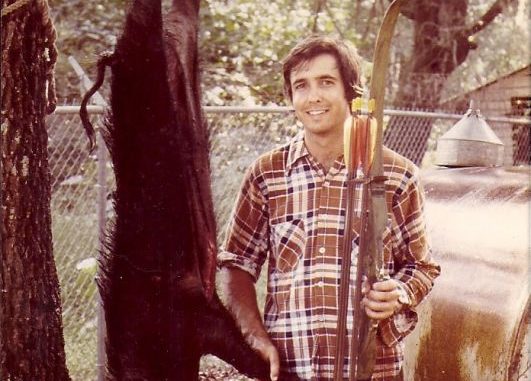

I first encountered feral hogs in 1976 when I went to work for LDWF as the game biologist for Southeast Louisiana, which included the Pearl River WMA. Pigs were common on the Pearl, and had been for years.

I killed my first hog with my old Bear Kodiak recurve bow while slipping along the edge of the Oil Well Road, which was under construction. It was a perfect double-lung shot, and the young hog made a small circle in the brush and died. The work, of course, was getting it back to the vehicle.

In those days hunters killed many more hogs than deer. We made a detailed survey of the hunter harvest on the area in 1978, and I think we put our hands on over 600 dead hogs.

I have always enjoyed hog hunting on Pearl River. Usually we combine a squirrel hunt with some pig hunting, and, of course, we are always on the lookout for pigs during the deer season.

Pigs are intelligent animals that wise up to us hunters in quick fashion, which make them quite challenging.

When we bought our property in East Feliciana Parish in 2007, we discovered hogs on our landscape, and I really enjoy the challenge of hunting them at night. Just when you think you have them figured out and get set up for the kill, something happens and the pig is a no-show.

Just recently I was set up for some hogs that were coming at 4:30 a.m. There was a change in weather conditions, and the hog had come at 10 p.m. Here I am sitting in the rain, and the hog had already been to the bait and was probably laid up out of the rain in a thicket.

Our property is in the Amite River drainage system, and there are plenty of feral pigs that come and go. For the past few years we have probably killed 10 or so a year, but this year the hunting has been slow. I killed one 2-year-old boar in late spring, and had another coming to the bait but could not find time to sit on it.

When the bait is gone, you have to start all over and get their attention again. It has been wet this spring and summer, and the pigs might be finding all they need in the sloughs and creek drains. I have yet to get any photos of a sow with piglets this year.

If you think I am a fan of the old feral hog you are right. As I said, I find them to be a very challenging wild animal to hunt.

Now don’t get me wrong: I am not in favor of designating them as game animals. I fully understand the detrimental effects they have on the landscape, to agricultural crops and to the forest along with the tremendous economic loss from this damage. The disease issue is also a concern.

It is, however, somewhat puzzling that we have had so many pigs on Pearl River in the past but disease was never an issue.

I like their designation as an outlaw quadruped; it gives me something to hunt year round, and keeps this old man active and somewhat in shape.

And unlike DeSoto, I find them to be excellent table fare.

What is a trophy boar?

Since the feral hog is not considered a game animal and is listed as an outlaw quadruped, there is no official recognition of a trophy boar. Many hunters, however, do have the heads of large boars mounted and hung on the wall in game rooms.

So what qualifies a hog as a trophy? Generally, most hunters look at the tusks, the lower canines known as the cutters. Some of the literature states that these tusks can be 3 to 3 ½ inches in length from gum line to the tip.

Of course, weight can be another qualification for trophy status, but if the food supply is abundant, young boars can weigh 200 plus pounds.

For me, age is the key to recognizing a true trophy boar. Aging hogs is similar to aging deer: tooth wear, eruption and replacement of teeth in the lower jaw.

Pigs have temporary teeth that will wear and are replaced with permanent ones. From what I have observed, the key is to look at the stage of development of the third molar. One- and 2-year-old pigs do not have any eruption of the third molar. At 3 years of age the third molar is beginning to erupt, and at age 4 the molar is fully erupted and the cusps of the other molars are beginning to show good wear.

In my opinion, to qualify for true trophy status the boar has to be 4 years old or older. At that age the skull is fully developed.

Skull measurements would, I think, be the best indicator of trophy status (similar to B&C measurements for bears and cougars). The height of the upper skull, from the top crest to the lower styloid processes; the length of the upper skull; and the width of the upper skull.

Of course, measurements of both the upper and lower tusks could be considered: the length of the tusk, the width of the tusk and the greatest flare of both the upper and lower tusks.

I have been playing around with some of these measurements, and definitely the 4-year-old and older hog skulls are larger than the ones for 2- and 3-year-old boars.

Records are made to be broken

I wrote last month about breaking my 42-year-old largemouth bass record. I caught a 6-pound, 8-ounce bass in June that was a pound heavier than the one I caught in 1971.

I mentioned that I hoped it would not take that long to break this new record. Well, one month later I was casting a watermelon colored Ribbet at daylight when a bass grabs the frog and the fight was on.

A few minutes later, I was holding a 10-pound, 4-ounce bass that demolished the record I just set for myself.

With this kind of luck (and a reel with braid instead of nylon), I just know my 135-inch B&C record is going to be broken this fall.