Part 1: Biology

The glamour boy of the grouper family, the 800-pound Atlantic goliath grouper, is becoming the Gulf of Mexico’s latest fisheries management football, to be passed and punted back and forth between recreational fishermen, commercial fishermen, environmentalists and fisheries biologists.

It’s hard to know what is more intriguing: the biology of the fish or its management.

Many who fish offshore where this fish lives might not recognize the name “goliath grouper,” still calling it by the name given it over a century ago — “Jewfish.” The name was changed in 2001 by a panel of scientists with the American Fisheries Society, who deemed the old name “potentially offensive.”

Political correctness hasn’t affected its scientific name, Epinephelus itajara, though. The fish was given its technical name in an 1822 publication on the natural history of Brazil.

The genus name is derived from the Greek “epinephelos,” which means “clouded.” The specific name “itajara,” is supposed to mean “lord of the rocks” in the Tupi-Guarani Indian language of Brazil.

The species is found along the Atlantic Coast from North Carolina through the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean down the South American coast through Brazil.

They are fairly easy to separate from other groupers, with their tubby body shape; very broad, flat heads; and small, beady eyes. A failsafe identifying feature is that all the spines in the spiny part of the dorsal (back) fin are shorter than the soft part of the fin.

Adults over 4 feet long are generally brown in color with darker brown spots on the body and fins. The spots on the tail are arranged in dark, vertical bands. Smaller fish are lighter in color, with olive overtones, and have five broad, darker, vertical bars arranged on their bodies.

Goliath groupers are long-lived fish, to at least 37 years old. Growth averages 4 to 8 inches a year for the first six years of their lives, slows to 1 to 2 inches annually by age 15 and to less than ½ inch per year after age 25.

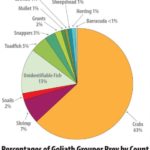

Their growth is fueled by a diet heavy in crustaceans, especially crabs and particularly box crabs (bashful crabs) that live on sandy bottoms offshore. A recent food-habits study done in Florida showed that fish made up only 28 percent of their diet.

For such a glamorous fish, surprisingly little is known about their reproductive lives. Only two females have been examined for fecundity (number of eggs carried). A 53-inch female was estimated to have 39 million eggs, and a 56-incher was estimated to have about 56 million eggs.

It is known that they mature at 5 to 7 years old and 43 to 47 inches long. Groupers in general are known for changing sex during their lives. They start life as females, and at a certain size change to males. Scientists don’t know if this holds true for the goliath grouper or not.

Generally, male goliath groupers are slightly larger and older than females, but some research indicates that males mature at an earlier age than females. Other research shows that the youngest and the oldest fish were female.

Goliath groupers definitely have a quirky life cycle. Adults take residence on rugged, high-relief bottom features such as reefs, shipwrecks, rock piles and ledges and, yes, offshore oil and gas platforms. They are not deepwater fish, usually found at depths of less than 150 feet and never deeper than 260 feet.

With the exception of seasonal spawning movement, most adults will move a half mile or less from their home territory. They do venture out over nearby sand and mud bottoms to feed.

During the months of August to October, adults form spawning groups of up to 100 fish called “aggregations.” Adult goliath groupers will travel up to 300 miles to join a spawning aggregation. During October and November, the adults will move back to their resident sites.

No goliath grouper spawning has ever been found outside of these aggregations, and spawning aggregations have been found only in the southeastern Gulf off of Florida, in the Atlantic Ocean off of Florida and in the Caribbean.

None have been found in the western or northern Gulf of Mexico. The once-large populations of goliath groupers off of Louisiana were thought to be “spill-over” on the edge of the fish’s range.

Once fertilized, goliath grouper eggs spend about six weeks drifting and developing in open waters. In what is the oddest part of their life cycle, the larvae that hatch from the eggs of this offshore species will settle out in shallow mangrove habitat, which in the Gulf of Mexico is restricted to southern Florida.

One usually thinks of reef fish such as snappers and groupers spending their entire lives offshore, but goliath groupers begin their lives hiding in mangrove leaf litter on the mucky bottoms in shallow waters along the shore. Juveniles can survive in waters with salinities as low as 5 parts per thousand (full strength seawater is 35 ppt), which is unusual for groupers.

As they grow larger, they move to undercut or overhung banks and submerged dead trees, still in the mangroves. Young fish have even been found in stagnant brackish-water canals, although their preference is definitely for mangrove-forested shorelines. After five or six years, they move to their adult habitat offshore.

Mangroves appear to be vital for the survival of young goliath groupers, which biologists fear might be a long-term problem for the species. In the Gulf, mangroves (not counting the black mangrove such as we have in Louisiana, which is not a shoreline tree) are restricted to southwestern Florida. Mangrove habitat in Florida has declined since 1900 due to development and channelization to redirect freshwater flow from the Everglades.

Not surprisingly, known spawning aggregations of goliath groupers in the Gulf of Mexico are near mangrove habitat. It appears that the goliath grouper populations of the entire Gulf, including off of Louisiana, are derived from the mangroves of southwestern Florida.

The dependence of these fish upon mangrove swamps could pose another problem. Two environmental factors can cause mass mortalities in goliath grouper populations: red tides and cold temperatures.

Red tides affect mostly adult fish. During 2003 and 2005 red tides, 57 percent of the goliath grouper carcasses recovered by scientists were over 48 inches long.

Cold snaps, on the other hand, kill young fish found in shallow-water mangrove habitat. Cold weather kills occurred in southern Florida in 2008 and 2010. Studies made after the 2010 kill indicated that 90 percent of the population was wiped out. Since the fish spend the first five years of their lives in mangroves, a kill such as this would take out not just one year’s spawn, but rather five years of spawned fish.