Some lay eggs, some bear live young

The word “shark” covers a lot of ground, with 55 individual species in the Gulf and Atlantic. For decades, most thoughts that sportsmen had of sharks were negative: they “stole catches off of their lines,” they damaged their tackle and they were dangerous.

Just when their (mostly) delicious table qualities came to be recognized, the federal government, spurred by environmental groups, stepped in and decreed that most sharks were overfished and needed massive protection.

The resulting rules declared a bunch of species as completely protected, lowered the bag limit on most of the rest to one per boat and put big minimum sizes on almost all of what could be caught.

Finding most sharks difficult to identify, with the risk of keeping a protected species and getting a ticket, most sportsmen simply threw their hands in the air and went back to lumping them all together as nuisance species, releasing them after whacking them on the head to pacify them.

But sharks are interesting and complex creatures. Take for example how they reproduce. Most of the over 20,000 species of bony fish (sharks have no bones) on earth spawn tens of thousands to millions of tiny eggs, counting on the sheer numbers of their eggs to produce enough survivors to replace them.

But sharks are different. They produce small numbers of large, well-developed young that can fend for themselves and therefore have a high survival rate. Depending on the species, the number of sharks produced per litter is small, ranging from two to 25, although large females of a few species like tiger sharks can produce litters of 100 or more pups.

Boys and girls at a glance

Gender in sharks is easy to identify. Males have a pair of very noticeable tube-like extensions of their anal fins called claspers. Connected to the claspers inside a male’s body is a pair of siphon sacs, essentially contractible bags filled with sea water.

Males store sperm in sacs in their bodies. Then, during mating, the male turns his claspers forward and inserts one into the female. Contraction of the siphon sac blasts sperm sacs through the clasper and into the female.

This mating procedure is pretty standard for all sharks. What happens next is highly variable depending on the species and family of shark, but their mode of reproduction falls under oviparity, ovoviviparity or viviparity.

What is oviparity?

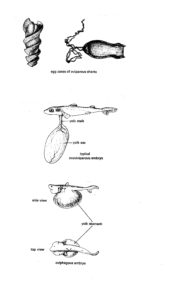

Oviparity is the biological term for “egg-laying,” and is the most primitive method of reproduction in sharks. Unlike bony fish, which lay delicate, shell-less eggs in large numbers, oviparous sharks protect their eggs with a shell of sorts.

The eggs are large, with enough yolk to nourish embryos until they are fully formed. The tough leathery-shelled eggs, sometimes called “mermaid’s purses,” are deposited on the sea floor, often attached to plants or bottom debris.

They are not guarded by the female and may take several months to hatch. Compared to other shark pups, those from oviparous sharks are smaller because their growth before hatching is limited by the amount of yolk in the egg.

Oviparity is only found in four shark families: some nurse sharks, bullhead sharks, catsharks and whale sharks.

Ovoviviparity is different

José I. Castro. Texas A & M University Press. 1983

Female ovoviviparous sharks also produce eggs, but rather than lay them, they hold them inside their bodies until they hatch. After hatching, the embryos continue to grow, using the yolk from their attached yolk sac. Both the yolk sac and the yolk stalk are completely absorbed before the pup is born.

It is thought that in some sharks, like the tiger shark, the lining of the female’s uterus produces liquid foods that are absorbed by the embryos after they deplete the yolk sac.

In species like the sand tiger shark, the young use up their yolk very early. After that, they continue to grow by practicing cannibalism, feeding on unhatched eggs and smaller pups in the litter. Such sharks are called “oviphagus” or “oophagus,” and often have huge, swollen stomachs from eating other yolks. Usually, only two pups survive to hatching, one in each uterus.

Ovoviviparous sharks include the white shark, mako sharks, thresher sharks, sand tiger sharks, and some dogfish, nurse and catsharks.

Viviparity is most advanced

The most advanced form of reproduction in sharks is viviparity. In these sharks, the embryos start out dependent upon a yolk supply, but the yolk sac develops early into a placenta and the yolk stalk into an umbilical cord.

The placenta taps into the mother shark’s bloodstream to feed the embryo. In some viviparous species, the mother produces liquid nutrients (often called “uterine milk”) that bathe the embryos. The pups are born alive and ready to feed and defend themselves.

Viviparity is found in many shark species, including, but not limited to hammerhead sharks, bull sharks, blue sharks, blacktip sharks and smooth dogfish sharks.