Tired of fighting for space at the popular snapper rigs? Move a little farther west to find easy pickings in Ship Shoal.

The charter captain yelled encouragement as his six-man crew slowly roused themselves from the hour-long trip out of Wine Island Pass.

“Let’s get some bait in the water,” Tommy Pellegrin shouted, peering out from under his Panama Jack hat as he worked the controls to hold the boat in place. “Come on, let’s go.”

Four baits finally hit the water, disappearing in the emerald murk and hitting the bottom about 85 feet down. The last two anglers lounged in the back of the boat, waiting to see what would happen.

Seconds later, two rods were bent, and the hold-outs grabbed equipment and headed for the bait.

Red snapper after red snapper began hitting the deck, Pellegrin and his deck hand moving from line to line to pop the fish off the circle hooks and drop them in the box.

Nothing had to be measured: All the fish were in the 3- to 10-pound range.

“Those are perfect eating size,” Pellegrin said.

About 30 minutes later, he called for lines to be reeled in.

“Let’s go look for some bigger snapper,” he said.

There were 23 nice snapper cooling in the ice chest, leaving only nine to go before the boat’s limit was reached.

“That’s a Ship Shoal snapper bite,” the skipper bragged, a slight grin creasing his face.

The next rig was seemingly devoid of fish, a strange thing because there were only a few miles separating it from the first stop of the day.

Pellegrin wasn’t phased; he simply punched a few buttons on his GPS and pointed the bow of his big Gravois toward another rig.

Water turned from green to light blue, although not the cobalt blue of far-offshore waters, as the crew of anglers hopped rigs farther south.

Almost every rig held snapper, and the boat’s limit was soon closed out. Although the 20-pounder Pellegrin wanted never broke the surface of the water, the snapper cooling in the fish box ranged from a few pounds up to one about 15 pounds.

The amberjack were a little heftier.

Then a couple of cobia showed up, and the boat’s occupants went into warp speed trying to get baits in front of them.

Pellegrin reached up to the T-top and grabbed a spinning rig on which a large jig was tied.

He ran to the front, as anglers shouted encouragement.

“There they are,” rang through the air in seeming stereo as the fish leisurely snaked away from the boat and down the side of the rig.

They were inches from the surface.

Pellegrin shot the jig out, but took great care not to cast at the lings.

“You don’t want to cast right on top of lemonfish,” he said. “They’ll spook.”

In fact, the cast was actually behind the cruising fish.

Anglers glanced at each other in doubt, but then one of the lemons spun around and nailed the offering.

Pellegrin set the hook and handed the reel to Georgia’s Hugh Shockley.

The braided line sang as it was ripped through the water, the drag of the spinning reel providing harmony.

Shockley held on for all he was worth as the muscle-bound fish tried to make for the rig.

Five minutes later, the big cobia showed itself.

“There’s another one with it. Those are huge fish,” one of the crew called as he hung over the side of the boat.

Another flurry of activity ensued, with Shockley being told to just hold his fish in the water.

Although looking aggravated, Shockley complied, and the 50- to 60-pound lemon danced under the water’s surface.

Another jig wasn’t available, so frozen sardines were tossed out on flat lines, but the second ling wasn’t going for it.

All the while, Shockley leaned against the big cobia.

And then tragedy struck.

Shockley tried to gain a little line to bring the rod tip down, cranking a couple of rounds on the reel handle.

Everyone watching the show over the gunnel saw the fish shake its head, and the jig popped free.

Shockley screamed something unintelligible before muttering something unprintable.

Everyone else groaned as they watched the pair of lemons just fade away.

But two more cobia were soon in the boat, although neither reached the size of the first hooked fish.

By 1 p.m., the crew was tired, and the fish box was full.

Pellegrin turned the boat northward and began fighting a sloppy quartering sea.

The only other boats seen the entire day were those servicing the proliferation of oil rigs dotting the Ship Shoal blocks.

And that’s why Pellegrin prefers making the very long runs to deep water instead of relocating his operation to more-popular rigs in the crook between Grand Isle and Venice.

“There’s no pressure,” he said of the Ship Shoal blocks southwest of Cocodrie. “You’ve got Grand Isle, Port Sulphur, Buras and Venice — where are they going to go?

“They all go to the same place.”

And he’s right. The rigs between South Timbalier and West Delta get pounded.

Ship Shoal has almost no fishing pressure, though.

“Over here, you’ve got Cocodrie, Cote Blanche, Cypremort Point, and that’s 50, 60 miles away,” Pellegrin said. “They’re going to go south of there.”

Of course, he does have to make long runs.

Anglers heading out of Grand Isle can find 200 feet of water in less than 20 miles. In less than 30 miles, they’re in 300 feet of water.

Boats leaving Fourchon are in 240 feet of water in just less than 30 miles.

Things are much different for Cocodrie captains.

Ship Shoal water depths 30 miles out of Wine Island Pass haven’t broken the 100-foot mark.

The 240-foot contour is another 20 miles farther, at its closest point.

So Pellegrin regularly makes 50-mile runs to fill his customers’ ice chests, but it’s a sacrifice he’s willing to make.

“You don’t have to fight other boats,” he said. “The fishing is usually better here than to the east.

“The average time to catch our limit of snapper is about an hour.”

But Pellegrin rarely sets his GPS for the farthest rigs first.

“I fish closer first, and work my way out,” he said. “That way, if I catch fish close in, I don’t have to run so far out.”

That was his strategy on this blustery day.

The first stop, which produced 70 percent of the 32-fish limit, was a mere 30 miles out of the pass.

By the end of the day, however, Pellegrin had worked from those 85-foot depths to about 200 feet 45 to 50 miles out of Cat Island Pass in search of AJs.

By June, finding concentrations of red snapper will mean a longer run.

“You want to start making that 100-foot line,” Pellegrin said.

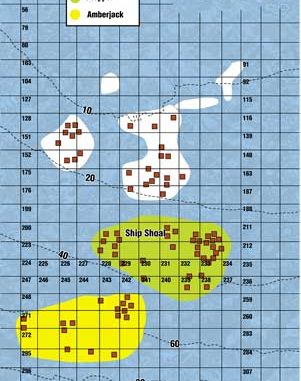

His daily targets this month stretch from block 227 on the west to 213 on the east, and from block 207 in the north to 238 and 239 in the south. All of these rigs sit in between 120 and 240 feet of water.

That’s where he grabs the bulk of his red snapper.

“I catch my limit of snapper first, and then I can go do something else,” he said. “It usually takes an hour, an hour and a half, and then you’ve got the rest of the day to play.”

And he wants as much time as possible to play.

“You never know what you’re going to find,” he said. “You might come across a weed line. Then you’ve got dolphin, wahoo, whatever.”

His strategy for finding snapper is pretty simple, yet extremely effective.

First, there are certain rigs that interest Pellegrin.

“Older rigs are better because of the reef system that has built up under the water,” he said. “A newer rig won’t have the barnacles and other reef growth that attracts the fish.”

He was quick to point out that the rig above the waterline should be ignored, since even the oldest rigs can be painted to look like new.

“You want to look at the water level to see how old it looks,” he said.

He also is more apt to target rigs with separate structures joined by bridges or scaffolding.

“I tend to like rigs that are split into two different structures,” he said. “It gives (the fish) those two different reefs, and you catch them migrating in the open water between those areas.”

The first thing Pellegrin does when approaching a rig is to make a pass around the entire structure.

His eyes are fixed on his fish finder.

He’s searching for big blobs of color that signify large fish below his boat.

“There’s some,” he said, pointing to several distinct patterns just less than halfway between the surface and the ocean floor. “There’s some more on the bottom.”

The bottom findings were harder to see.

“You see how the bottom line gets fuzzy-looking? That’s fish,” he said.

Even though he marked those fish, Pellegrin continued around the structure, checking to ensure there weren’t larger concentrations elsewhere.

Almost invariably, he finds the fish on one particular side of the structures.

“I tend to find the fish mostly on the southwest sides of the rigs,” Pellegrin said.

The reason is that fish tend to hang on the upcurrent side of a structure, and the prevailing currents in the Gulf during the summer months generally are from a southerly direction.

But the veteran charter captain said the fish don’t normally hang directly upcurrent of a rig.

“If the current is out of the south, I’ll usually find them on the southwestern corner of the rig,” Pellegrin said.

Similarly, if the current is flowing from the southwest, the fish will likely mass on the western and southern sides of the rig.

“They like to be on the edge of the upcurrent side,” Pellegrin explained. “That’s where you find your schooled-up suspended fish.”

And that’s important to his approach.

“I like to fish suspended fish because I don’t have to fish the bottom, and I don’t have to reel them up as far,” he said.

Of course, surface currents can be deceiving.

“Sometimes you’ll have a dual current, so you have to be aware of what’s going on,” he said.

That means the boat could drift southward, while the prevailing subsurface current is ripping northward.

While many anglers prefer to tie to a rig before fishing, Pellegrin’s approach makes that impossible unless the surface currents allow.

But he usually just ignores the option.

“I might have tied off in the last 10 years maybe five times,” he said.

Instead, he mans the wheel, working his twin Yamahas to hold the boat in position.

That allows Pellegrin to make adjustments to keep the bait properly presented.

“You don’t want the boat to be over the fish,” he said. “You want the baits to be in the fish.”

To ensure that’s the case, Pellegrin watches his anglers’ lines to determine the angles.

“That’s where math comes in,” he chuckled. “The current could be ripping, and you might have to go way back.

“If it’s slack, you can be right on top of the fish.”

Being free of the rig also allows Pellegrin to help out when a big fish is hooked.

“I can move the boat away from the rig if I need to to keep a big fish from breaking off,” he said.

Anglers who tie their boats off don’t have that option.

There’s another benefit of leaving the rig hook at the dock — finding larger fish by moving the baits farther away from the main school being fished.

“When you get on a school of the little fish, start moving farther and farther out,” Pellegrin suggested. “A lot of times, you’ll find the bigger fish on the outside of the school.”

His standard snapper rig is a basic Carolina rig — 50- to 80-pound line tipped with 200-pound mono leader and a 7/0 Mustad Ultra Point circle hook. A sliding egg sinker large enough to overcome the current is placed on the main line north of the swivel.

Braid is never used for snapper.

“Braid is horrible for snapper,” Pellegrin said.

First, the extra-tough line is just too limber.

“It really twists badly with a Carolina rig,” he said.

But there’s an even more fundamental reason to avoid braid.

“It’s very sensitive, but there’s no stretch,” Pellegrin said. “When you’re fishing circle hooks, you need to have some give (in the line).”

With braid, the hooks are often ripped out of the fish’s mouths.

Monofilament, even at larger diameters, provides plenty of stretch to put the hook right where it needs to be.

Hanging from every hook of his snapper rigs will be frozen Spanish sardines.

“That’s the No. 1 snapper bait,” Pellegrin said.

He also likes to match a fairly light rod with the line assembly.

His favored rod is a 6-foot, 6-inch 12- to 30-pound-class Tica rod.

“It’s pretty much unbreakable,” Pellegrin said.

And the experience is better for the angler than when forced to crank snapper up with a heavy-action pool stick.

“You play the fish more,” he explained.

Coupled with the rod is a Tica Gemini GN 300, with the drag set at a light 8 to 10 pounds.

“You don’t have those big reels with 20-pounds of drag,” he said. “This way, you actually have fun fishing all day.”

And the rigs proved that day to be powerful, even pulling up several decent-sized amberjacks.

Big AJs, those cresting the 40-pound mark, are a different matter, however.

These notorious fighters are best matched with heavy-duty rods and reels.

Once he’s filled out the day’s snapper limit, Pellegrin turns to these bruisers, juicing the engines and heading out past the 40-fathom contour.

“You’ve got to be in 150 feet of water or more,” he said.

That means he’ll cross into the Ship Shoal South Addition, namely blocks 252, 253, 269, 271, 272, 274 and 290 through 293.

He makes the same exploratory round around each platform, watching for fish on the sounder.

Meanwhile, he replaces the lighter tackle with heavy rods and Tica 30WTS reels spooled up with 80-pound mono.

However, he’ll sometimes turn to braid when battling beastly AJs.

The sturdy reels will be set at 20 to 25 pounds of drag to help keep the fish from running back into the rigs and breaking off.

“When you get to these real big fish, you need to get bigger because you’re out-classed with the light tackle,” Pelligrin said.

This is when being free from the rig really pays off.

“I can pull the boat away and keep the AJs out of the rig,” Pellegrin said.

While AJs will certainly gobble sardines, Pellegrin’s preferred weapon is live bait.

“You can’t beat live hardtails,” he said.

A 7/0 circle hook is threaded through the “shoulder” meat between the dorsal fin and the top of the head.

The soon-to-be-devoured bait is then dropped to the appropriate depth on the same Carolina rig used to catch snapper.

While hardtails were hard to come by on this trip, Pellegrin had stopped in the pass that morning and netted a few pogies.

They worked just as well as the hardtails.

“He’s getting nervous,” Houma’s Daniel Lopez chuckled just before an AJ walloped his bait.

Grouper is another species that calls for heavy tackle, not so much because they are as large or hard-fighting as an amberjack but because of where they set up shop.

“They live in the rigs themselves,” Pellegrin said. “I’ve got a couple of rods spooled with 80-pound braid, but that’s all I fish braid for — that and amberjacks.”

Cobia are fish that everyone loves to catch, largely because they often can be pitched to as they cruise the surface.

This is another application for braid, but it’s spooled onto heavy spinning reels and rigged with jigs. The rod is then placed in a rod holder to await action.

As shown earlier, Pellegrin prefers not to cast directly to a cobia.

“You saw that I threw it off to the side of it so I didn’t spook it?” he said of the big cobia hooked and lost earlier in the day.

His favorite plastics to thread onto his jigs are Old Bayside Mud Minnow Curl Tails in glow.

“That’s the best cobia bait,” he said. “If you get it anywhere near it, they’ll come get it.”

While some anglers use jigs as heavy as 6 ounces, Pellegrin said he prefers 2-ounce versions.

“If you’ve got surface lemonfish, when you pitch it out, it doesn’t sink too fast,” he explained. “If you pitch a 4- or 6-ounce jig, it’ll sink out of the way too fast.”

And while any rig can hold ling, Pellegrin said he definitely has a favorite type of structure.

“They’ll be around the little satellite rigs,” he said. “The smaller the better.”

So when he wraps up his snapper limit and puts a few bruiser AJs in the box, he’ll stop at these smaller rigs on his way in and take a few minutes to check things out.

Mangrove snapper are the least important to Pellegrin’s business, but he said they definitely teem around Ship Shoal rigs.

“They’ll be in the shallower rigs, in 30 to 100 feet of water,” he said. “The mangrove are better on top of the shoals.”

The reason he doesn’t mess with them too much is that they can be a pain.

“Sometimes you’ve got to chum them to get them going,” Pellegrin said.

That makes for exciting visual action, but actually convincing a fish to eat can be tough.

“They get kind of spooky on top, so you have to go with light line,” he advised.

But normally by the time he reaches these shallow structures, his anglers are tired and happy from fighting unpressured Ship Shoal fish in deeper water.

Pellegrin can be reached at (985) 851-3304.