Shallow duck ponds are favorite haunts of redfish, and the area north of Cocodrie is chock-full of potential. Here’s one guide’s tips for finding success.

The red was clearly visible, relaxing just on the edge of a marshy point of grass.It looked lifeless but for the slight, lazy movements of its pectoral fins that maintained its position.

Capt. Jimbo Dupre eased to the edge of his casting deck, and tossed a spinnerbait to the edge of the water several inches in front of the fish.

The effect wasn’t what he had in mind: As soon as the lure touched the water, the red streaked away, leaving only a distinct trail of mud to mark its passage.

“I don’t understand it,” Dupre said.

The Sportsman’s Paradise guide had been drifting shallow-water ponds north of Cocodrie for hours, spotting redfish only to watch in frustration as they spooked.

“The water’s a little too clear,” Dupre said.

It was nerve-racking.

Although the water appeared to hold some suspended sediment, the fish glowed like copper neon signs against the dark bottom.

Some fish spooked at the sight of the boat, but others appeared clueless to any presence but their own.

Even those reds refused to swallow a bait, however.

“There’s one,” Dupre said.

The fish was visible at first only by its signature wake moving across the front of the boat, but then it began to take shape.

I snapped my wrist, and an H&H spinner streaked to intercept the 20-inch red.

The lure parted the water quietly about a couple of feet in front and to the left of the fish.

Perfect, I thought.

The spinnerbait passed inches in front of the red as the fish continued to swim toward the bank.

“It’s turning on it,” Dupre said nervously.

The redfish followed the lure for a couple of seconds, and I had to resist the temptation to slow down the retrieve. Doing so, I knew, would result in the fish losing interest.

Nothing else happened until I sped the retrieve slightly.

The fish went bonkers, charging what it thought was a fleeing bait.

The spinnerbait disappeared in a huge swirl, and I felt a single tap.

Before I could even set the hook, the fish streaked back to open water — sans the spinnerbait.

“I can’t believe that fish didn’t take that bait!” Dupre growled. “It swirled all over it.”

I just shook my head in disbelief and kept looking for another target, craning my head from side to side to get the most out of my polarized Costa Del Mars.

That’s the way it went for hours. We’d see a redfish, and it would spook.

As maddening as the experience was, a thrill accompanied each sighting.

Fishing often becomes a practice in monotony. The lure is cast to a likely spot, and it’s reeled in. The lure is cast to another likely spot, and then it’s reeled in again.

Every now and then, a fish slams the lure and the angler gets to enjoy a fight.

But he can’t be sure the fish is the targeted species until it gets right to the boat.

Sight-fishing is different; the angler identifies the species before ever loosing his lure.

“Is that one?” Dupre asked.

I squinted in the direction he pointed at, saw a huge wake and readied to make a cast.

Then the fish came into view, and the black back and dark stripes on its side made it identifiable.

“Nope, just a sheepshead,” I said.

Disappointment replaced the flood of adrenaline initially coursing through my body, but I could take solace in the excitement of the hunt.

Finally, about four hours after we started, Dupre cast to a red spot about 10 yards off a bank.

The fish was prowling in a shallow cove, and it couldn’t resist Dupre’s offering.

“There he is,” the guide said, satisfaction and relief mingling together in the words.

The fish struggled, and Dupre worked the nice red.

And then the unthinkable happened.

Dupre’s spinnerbait came flying out of the water.

We both felt deflated, but I caught movement out the corner of my eye.

A tail was sticking out of the water about 30 yards from where Dupre hooked his fish.

“There’s one tailing,” I said, while shooting my lure past the fish.

The red wallowed around like a hog in a particularly cool mud hole, and then disappeared before I pulled the bait into striking distance.

Mumbling under my breath, I continued fishing.

And then I felt a familiar “pop” on the end of my lure, and the water erupted.

A hard set plunged the hook into the fish’s mouth, and the fight was on.

Three minutes later, the fish was in the boat.

The ice had been broken, even if the bite hadn’t come as a result of actually seeing the fish.

Dupre said such frustration and exhilaration is what draws him to sight-fish for reds.

“It’s just exciting,” he said. “You usually get to see the fish bite.”

The 22-year-old captain grew up in Cocodrie, and has spent most of his life probing the marsh ponds north of his hometown.

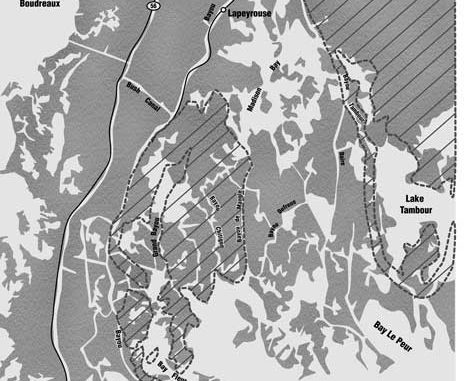

Although he’ll fish both sides of Highway 56, his favorite areas lay east of the road, stretching to Lake Tambour and from the northern shore of Lake Barre to Wonder Lake on the edge of Pointe-Aux-Chenes Wildlife Management Area.

“There’s just so many areas up here to fish,” Dupre said. “I’ve been fishing all my life, and I’ve never covered half of them.”

Dupre said there are two main section in which he concentrates his efforts.

The first is close to the launch at Sportsman’s Paradise.

This area is bordered on the west by Bayou Terrebonne and Bayou de Mangue, and stretches from the top of Bay la Fleur to Madison Bay.

The second area is even larger, covering the marsh from Lake Tambour to Wonder Lake between Bayou Tambour and Bayou St. Jean Charles.

“There are tons of ponds in those areas,” Dupre said.

While many anglers are tempted to just pick a pond and start fishing, Dupre said the chances of success are maximized by knowing exactly what to look for in a pond and what strategy to use.

His first rule of thumb is to find clear water.

But not too clear.

“I like a little bit of stain to the water,” he said.

That might sound strange, since his goal is to spot fish before casting, but Dupre said it makes sense.

“If the water’s too clear, they can see you. They get real spooky,” he said. “If there’s a little stain, the fish can’t see you and don’t spook as easy.”

Dupre also pointed out that his perfect ponds have some current, since moving water is important to redfish feeding habits.

However, this doesn’t mean he wants water to be ripping through a pond.

“I like ponds that are right off of a canal or bayou, somewhere where its forming current for the bait to stay,” he said. “The redfish are going to stay where the bait’s at.”

The reason this set-up is so successful is that the current pulling by the cut leading into a pond will create a little water movement in the pond itself, while also providing refuge for bait from the stronger current in the channel.

The presence of bait is essential to catching fish, Dupre said.

“The pond should have bait. That’s what holds the redfish,” he said.

Next, Dupre looks at the size of a pond.

“I prefer small ponds no bigger than a football field,” he said.

While he would never argue that large lakes don’t hold fish, Dupre said he focuses on small ponds for two reason.

First, they are less likely to be choked with grass.

But his real reason is even more fundamental.

“I find the fish just jam up in a little pond,” Dupre said. “It’s easier to locate them.”

So instead of spending an hour trying to locate productive banks in a huge lake, he can quickly determine if there are fish in a smaller pond.

He doesn’t, however, like to fish ponds with distinct banks. Instead, he’d rather a broken bank and small, scattered islands.

“I find the bait stays in that broken grass for protection,” he said. “I just troll the islands and little patches of grass; that’s where the bait is.”

A broken shoreline also provides plenty of current breaks

“Redfish like to sit out of the current, if possible,” Dupre said.

So as he trolls through a pond, he’ll cast to the coves and points formed by these grassy pieces of marsh.

“I’ll start fishing at the cut,” Dupre said. “If it’s round, I’ll just fish all around it, working the bank.”

Another characteristic he looks for is water depth. Specifically, Dupre wants sufficient water so that fish feel comfortable, while also allowing him to practice his sight-fishing strategy.

“I want 8 to 14 inches of water,” he said. “You can see the fish a little bit better.”

However, that can make fishing the ponds difficult.

Obviously, a shallow-draft boat is a necessity, and stealth is critical.

That’s because fish spook at the sound of hatches banging shut or the hull scraping on oyster shells.

And fishing during low tide is pretty much precluded.

In fact, Dupre stayed away from the ponds all that morning, stalling the redfishing until the tide began to rise.

But that’s not really heart-breaking because the fish generally aren’t in the ponds then anyway.

“Once the water gets too low, the fish start pulling back to deeper water and scatter out,” Dupre said.

So he bides his time, fishing other, deeper waters until the tide turns.

“I’ll pull out into the main lakes,” Dupre said. “The fish just pull out into those areas because they can find enough water.

“But they’ll still be along the shorelines.”

Once water begins moving back into the marsh, however, Dupre is ready to hit the ponds.

Experience has taught him not to just charge back into the ponds as soon as the tide turns, however.

“I like to wait until about two hours after the tide starts moving in,” he said. “That gives the bait time to move back into the ponds, and the redfish follow them.”

But his favorite time to chase Cocodrie’s shallow-water reds is on a falling tide.

“That first couple of hours of the falling tide is what I like to fish,” Dupre said. “Your water’s still high enough for you to get into the ponds and hold fish, but the water is moving and the fish are feeding.”

All he has to do then is be quiet and put a bait in front of the fish.

Dupre can be reached by calling Sportsman’s Paradise at (985) 594-2414.