Stock assessment through 2013 indicates no problems with fishery

Many trout anglers sounded an alarm earlier this year, when their catches didn’t seem to measure up to expectations.

Biologists at the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries said at the time that they didn’t believe there was any cause for alarm.

And a recently completed speckled trout assessment seemed to back up that stance — at least through 2013.

“From a biological perspective, we are in fine shape,” said LDWF’s Harry Blanchet.

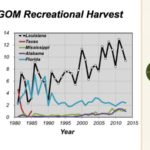

The assessment, which was presented today to the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Commission, reviewed data from the early 1980s through 2013. It took into account harvest data and information collected by biologists.

Blanchet pointed out that the recreational harvest data gets shakier the farther back in the data you move.

“We do not have a whole lot of recreational harvest data prior to the early 1980s, and even in the early 1980s, sampling data was not very good,” he said. “As we moved on, we ended up making more collections and collecting more data.”

The upshot for anglers is that the recreational harvest in Louisiana has trended higher over the past 35 years — and is significantly higher than any other Gulf state.

“We are the center of the speckled seatrout universe,” Blanchet said. “If you want to land trout, this is the place to go.”

Information collected from fishermen is then combined with data from LDWF staffers, who go out into the field to collect samples at prescribed locations across the coast at prescribed times.

That provides data from consistent data points, with no variations because of fishing pressure.

As part of their work, biologists have always estimated ages of fish. But even that data has tightened up with the most-recent analysis.

“One of the main differences between the assessments we have done before and the current assessment is the means by which we apply ages to the harvest,” Blanchet said. “We know that so many fish (in a population) are 12 inches long, 13 inches long and so forth. In prior years we used a growth equation to estimate what that age was. In prior assessments, if we had a 12-inch fish, that would come across (in the data) as a fish approximately 1 year old.”

That changed in the current assessment because biologists have gone the extra mile to learn more about growth rates for females.

“(W)e take (fish’s) otolith, take sections of the otoliths and count age rings,” Blanchet said. “From that, we see we have some (12-inch) fish that are less than 1 year old and some that grow faster.”

This allows biologists to look at more-accurate age-distribution models.

When all the information was put together, biologists get a better picture of the health of the fishery.

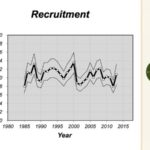

“One of the things that comes from the assessment is the estimated recruitment,” Blanchet said.

Recruitment is simply the number of young fish coming into the fishery.

And Blanchet said year-to-year changes aren’t that important. Instead, they pay close attention to the long-term trend.

“What we’re looking for here is how things change over time,” he explained.

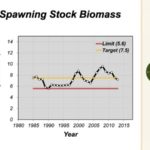

Biologists also glean information about the spawning stock biomass, or the weight of females of spawning size in the population.

Blanchet said their information in this area indicates no real problems, despite changes from one year to the next.

“Again, you see there is some fluctuation, but overall we are within the range we’ve seen historically,” Blanchet said.

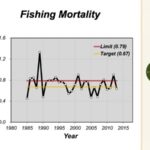

And, finally, fishing mortality — the estimated rate at which people remove trout from the population — was considered. And, predictably, of most interest to biologists is the long-term data instead of focusing on any specific annual change.

“What we are looking at is are there some significant trends?” Blanchet said.

When a huge spike in the fishing mortality rate in the late 1980s was pointed out by a commissioner, Blanchet said there were several hard freezes during those years — but he added that it would take much more work to determine if those cold blasts were responsible for the increase in fishing mortality rates.

“Stuff happens,” Blanchet said. “We’re not too concerned about a single point or two being over (the) limit, as long as we don’t have a trend over the limit.

“Things look about what we have seen in the past.”

He said stock recruitment is a key consideration, and the data doesn’t point to anything other than a sustainable population.

“The real question is, if you have a certain number of females in the water, what does that mean to the ability to add new recruits to the fishery,” Blanchet said. “The recruitment we have seen has not been off, but has been consistent … over the whole range.”

Current management goals strive for an 11-percent spawning potential ratio — a comparison of the spawning ability of a stock experiencing fishing and the same stock’s spawning ability if no fishing existed.

The current assessment revealed the SPR has ranged from 8 percent to 14 percent through the life of the study. But even the lower SPR percentages shouldn’t indicate any real problems.

“Over that entire range (from 8 percent to 14 percent SPR), trout demonstrate sustainability,” LDWF’s Joe West said.

The take-home message is that Louisiana’s trout population seems to be in great shape, the biologists said.

“The stock … is replenishing itself,” said LDWF’s Randy Pausina, who heads up the agency’s fisheries staff. “From a biological standpoint, we’re right where we should be.”