Deer are under pressure from urban sprawl, hog invasions and disease, but there’s an argument to be made that Louisiana hunters are living the high life.

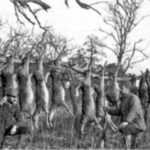

By the turn of the 20th century, Louisiana’s deer herd was in trouble. Non-stop hunting by people trying to put meat on the table, and market hunters supplying restaurants with venison and leather clothiers with hides was pushing the herd to the brink.

So many deer were killed that their hides sold for as little as $1 each.

In 1910, Florida’s San Mateo Item reported that hide hunters were slaughtering the deer along Cocodrie Bayou in Concordia Parish. The paper claimed that the Cocodrie swamp was “the greatest natural deer park in the world,” but an estimated 500 deer had already been killed that season.

For a $1 commercial license, the hide hunters were depleting the herd locals depended on for food.

“The people of Concordia Parish are naturally outraged,” the paper reported. “If such destruction is continued it can mean only the extermination of deer along Cocodrie Bayou and if such slaughter takes place in one swamp … it may take place in a dozen others ….”

Biologists estimate that Louisiana’s deer population dropped from several hundred thousand in 1700 to an estimated 70,000 animals by the early 1900s.

In some areas, deer disappeared completely.

Fortunately, things were beginning to change. A movement known as Progressivism was sweeping the nation and pressuring the government to correct such chronic abuses as pollution, corruption and child labor.

In 1900, Iowa Rep. John F. Lacey extended the progressive agenda to wildlife when he introduced the Lacey Act.

The first federal law to protect wildlife, the Lacey Act helped curb market hunters’ activities by prohibiting the interstate transportation of venison and other wild game.

Louisiana climbed on the Progressive band wagon in 1912 when it created the Department of Conservation and gave it the authority to regulate all activities regarding the state’s wildlife.

In setting Louisiana’s deer season that year, the Commission outlawed the killing of does for the first time, required bucks to have antlers at least 3 inches long and limited hunters to five bucks per season.

The selling of venison was also prohibited (another first) but, oddly, spotlighting remained legal.

Not surprisingly, politics eventually came into play when locals began complaining about state authorities controlling hunting seasons in their parishes.

As a result, the Department of Conservation set the 1946-47 season to run no more than 45 days between Nov. 1 and Jan. 10, but it allowed each parish police jury to decide which 45 days hunting would be allowed.

This became the norm, and police juries continued to control hunting seasons for years to come.

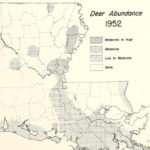

By the late 1940s, most of the deer were concentrated in 16 parishes, but even in those regions the herd density was just one per 74 acres. There were so few deer, in fact, that only 15 percent of the state was open for hunting in the 1948-49 season, and less than 1,000 deer were harvested.

To improve the situation, the Legislature agreed to fund a program to restock deer in depopulated areas.

For the first round of stocking, the Department of Conservation acquired 100 deer from the Texas Arkansas National Wildlife Refuge and 100 from private preserves near Minden and Hammond.

Encouraged by the results, biologists took additional deer from Marsh Island, Chicot State Park and even Wisconsin.

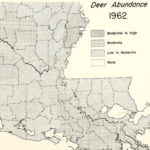

During the 1949-69 restocking program, 3,378 deer were released in nine regions. Fairly quickly the deer population exploded and hunting improved.

While less than 1,000 deer were harvested in the 1948-49 season, 16,500 were taken in 1960-61.

By the late 1960s, the deer herd had recovered enough to allow hunting in nearly all of the state, but the season was considerably shorter than today.

Gun season usually opened in early November, and then closed for a week or so. It reopened for another few weeks in December.

The dog hunting tradition was revitalized in areas where deer reappeared, and deer season became an important social event for the community. Men and boys spanning several generations spent the day making drives, visiting and reminiscing about the old days.

Nearly everyone used shotguns loaded with buckshot, although most hunters carried a couple of “bear balls” with them in case a long shot presented itself. The rare hunter armed with a Winchester .30-30 or some World War II relic would usually be assigned to cover a pipeline.

There was no hunter orange, camouflage clothing, insulated boots, waterproof GORE-TEX® jackets or ATVs. Coveralls and farmer’s overalls were standard. Leather work boots were pulled over several layers of cotton socks, and work gloves warmed the hands on cold days.

As deer became more prevalent in the 1970s, one or two doe days became common in most parishes, and still hunting gained in popularity.

Technology also began to have an impact on an old tradition. Metal leaning stands, deer calls, cover scents and camouflage clothing became standard, and scoped rifles began to replace shotguns as the preferred weapon.

Some hunters looking for a greater challenge even turned to black-powder rifles and archery equipment.

This technological change has continued ever since. Recurve bows became compounds, and compounds led to crossbows. Traditional Hawken-style rifles gave way to scoped muzzleloaders with synthetic stocks, and now some centerfire rifles have even been approved for the “primitive weapons” season.

Deer hunting in Louisiana began to change fundamentally in the 1980s when large timber companies started leasing their property to private hunting clubs. Up until that time, hunters had free access to huge tracts of timber company land and most private property.

Leasing has led to a decline in both the number of hunters and the popularity of dog hunting. The former is the result of many people putting up their guns because they cannot afford hunting club dues, and the latter is because many leases are simply not large enough to accommodate the running of dogs.

If one judges success by the number of deer killed, the 1990s were the golden age of Louisiana deer hunting.

In each of the 1997-98 and 1999-2000 seasons, approximately 180,000 hunters bagged about 270,000 deer. Those are the best years on record, and they don’t even include data for hunters older than 60.

Many hunters have reported seeing fewer deer over the last decade, but former state deer program manager David Moreland believes the numbers will eventually rebound.

“The Baby Boomer generation killed a lot of deer, but many Boomers have slowed down with the harvest, and it seems most are interested in only shooting a good buck,” Moreland said. “So I see deer numbers increasing down the road.”

Despite that optimistic opinion, there are still some threats on the horizon that could affect our sport. People over 60 make up a third of the state’s deer hunters, and Moreland sees that as a potential problem.

“Since Louisiana in the 1950s and ’60s had a rural landscape and there was no leasing of the timberland, we Baby Boomers were connected to the land, and hunting and fishing were a major part of our lifestyle,” he said. “One day we will be gone, and what was important to us does not appear to be that important to the next generation.

“When we hang it up, the strong support for hunting will be gone.”

Other potential threats are the growing number of feral hogs and diseases.

Hogs compete with deer for food, and an unchecked hog population can mean trouble. Astonishingly, in the 2012-13 season, Louisiana’s hunters killed 8,000 more hogs than deer.

So far, diseases have not greatly affected the herd, but in 2012-13 there were 182 anecdotal or confirmed cases of epizootic hemorrhagic disease in Louisiana, with most reports coming from the south-central and southeastern river parishes. It and other diseases must be closely monitored.

Moreland also lists urban sprawl as a possible threat to deer hunting.

“Following Katrina, the Florida Parishes north of Lake Pontchartrain saw much new development,” he said. “You can also see this going on in Bossier Parish, in Baton Rouge and across the state. While deer will adapt, I’m not sure that hunting, especially with high power rifles, will be acceptable.

“I see more hunting with crossbows in these areas.”

For dog hunters, the future looks particularly bleak. Because of complaints about dogs running on adjoining clubs and private property, the federal government banned the sport on Kisatchie National Forest in 2013. Weyerhaeuser timber company, which owns huge tracts of land in North Louisiana, has also announced that 2014-15 will be the last season it will allow dog hunting.

Despite these concerns, it is still a great time to be a Louisiana hunter. Deer are found all over the state, hunting licenses are reasonably priced and we have a lengthy season with liberal bag limits (particularly in the taking of does).

In fact, one could argue that we are currently living in the good old days.