Pay attention to avoid bone-headed mistakes

We are all products of, and are shaped by, our individual collection of lifelong experiences and lessons, both good and bad.

Regarding me, the events and experiences of a particular fateful day several years ago will be forever ingrained into my mental archive. Sometimes the best lessons, never to be repeated, are learned the hard way — and my education on that day came unusually hard.

I well remember the vivid details like it all happened just yesterday.

It all began the evening before the opening morning of primitive weapons season. Having had the better part of a year to misplace or lose various components of my blackpowder kit, I busily scrambled and scrounged around in my gear storage area, opening drawers and cabinet doors as I found and gathered together shotgun primer caps, Pyrodex powder sticks and all of the other paraphernalia required to charge and use my 50-caliber muzzleloading TC Encore rifle.

The hunting regulations had changed a year or two before regarding what constituted a legal “primitive weapon,” and certain types of single-shot, break-action center-fire cartridge guns were now also legal to use.

Having made lots of one-shot, dropped-in-their-tracks kills over the years with a .50 black powder front-stuffer, I sensed no need to change what I was doing.

So, in spite of certain friends and relatives changing over to cartridge guns, I stuck with what had always worked well for me. After all, no matter which way you went, you only got one shot.

My introduction to blackpowder started about 35 years ago, and I will never forget the profound sense of accomplishment I felt after bagging my first blackpowder deer — a big, fat doe — one evening.

This was long before cell phones became common, so no one knew about my exploit until well after dark, when I burst through the kitchen door proclaiming in a loud voice that Davey Crockett was home.

Everything went well for a few years until the advent of Pyrodex powder, which was touted to not foul your barrel like black powder. I, of course, not wanting to be left out, jumped on the band wagon and bought a can of Pyrodex — but did not bother to do any real advance research on just how it differed from black powder when it came to ignition.

As luck would have it, my lesson was learned in the field, as a massive 10-point buck slowly walked by with his nose to the ground about 10 yards away from where I knelt.

There was only a sickening “pop” from my blackpowder cap and a miss-fire when I pulled the trigger. My jaw dropped in disbelief, as I watched the buck of most hunter’s dreams bound away.

In my haste to keep up with the Joneses, I had not bothered to ask anyone if my old-style caps would still work with the new powder. I subsequently found out that Pyrodex was harder to ignite than standard black powder, so I immediately changed over to pistol primers and never had that problem again.

It has become painfully obvious to me over the years that such lessons, for me at least, are only learned when a trophy buck is in my sights.

Now let’s return to the original story. By the time I had looked over all of my gear and laid out my hunting clothes and kit, it was well past a sane bedtime for a 4:30 a.m. wake-up. I hurriedly took a shower and hoped into bed, hoping for at least a few hours of decent rest.

My hunt the next morning was rather uneventful, and after coming back to the camp for lunch, we sat around eating and resting before the afternoon hunt.

The main topic of conversation naturally centered on where we should each go to have the best chance. I was most interested in trying to bag one of the big, mature bucks that we had been seeing on our web of scouting cameras, so I opted for a ladder stand on top of a ridge overlooking a small, secluded food plot.

We had a couple of cameras within sight of this stand that had yielded several photos of targeted mature bucks in recent days. The wind was right for both the stand and the approach, so that is where I chose to go.

After donning my gear and driving down the public blacktop road to a convenient cut-through trail head, I began the short hike into my chosen spot. Walking the trail as rapidly as possible, while still scanning ahead and remaining vigilant, I replayed in my mind the reasons why I was headed to this particular spot.

I began to feel a weird sensation that I am certain many of you have felt as well. It was almost like a premonition, a little voice in my head that actually said, “You are about to make a mistake.”

As I closed on the stand site, alternatives were swirling around in my head, and a vivid and almost palpable sense of doubt swept over me. Slinging my rifle across my back, I began to slowly climb up the ladder stand, pausing briefly before swinging up into the seat.

As sudden and as well defined as a lightning bolt, that same internal voice clearly said, “Stop, go across the ridge and down slope to that other ladder stand about 150 yards away out on the ridge nose overlooking the big hardwood creek bottom.”

The eerily subliminal pull was so strong that I almost sprang down the ladder, and half-trotted all the way to my new destination.

Arriving at the new site, I climbed up and settled in for the late-afternoon hunt. I probably wasn’t in the stand more than 15 minutes before I began to hear the shuffling of leaves off to my right.

Pulling up my binoculars, I was pleasantly surprised to see a buck with what appeared to be a nice rack slowly browsing acorns as he meandered in my direction. His rack continued to grow in size as he drew closer and was more visible.

It became obvious that I was looking at a fully mature, at least 5 ½-year-old buck. He was a perfectly symmetrical main frame 8 with long main beams, really good mass and respectable tine length.

He was probably plus or minus 140 inches, but mainly he was fully mature. I personally go for age over inches any day of the week.

Pulling the 50-caliber Encore up to my shoulder and shifting to the right, I prepared for the shot. When he closed to about 20 yards and disappeared briefly behind a large oak, I cocked the hammer, and as he reappeared I aligned my scope’s crosshairs on his upper left shoulder and began a slow squeeze.

There was a thunderous report as the rifle fired, and I was almost knocked out of the stand.

Somewhat confused, I watched the buck crash off into the creek bottom, dragging his left leg.

Quickly climbing down, I gathered my gear together, and prepared to go and collect my buck; it sounded like he went down just out of sight on the other side of a nearby cane thicket.

At such close range, with a solid rest, and a scope set on 2x, the odds of recovering this buck were virtually 100 percent — or so I thought.

The subsequent late-into-the-night tracking job yielded a fair blood trail and one sighting of the buck as he continued to get up and move when we got close. As a result, we backed out and decided to resume the search the following morning.

As luck would have it, there was just enough overnight precipitation to wash out the blood trail from the point where we had stopped following the buck. Even though we looked and looked all day long, we never found the buck, but did thankfully find out later that we had pushed him out of that block of woods and a neighbor had harvested him when he came by dragging his broken and useless left front leg.

I felt really bad about what happened, but was gratified in the end that he had not gone to waste.

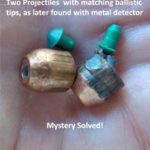

The mystery of why my gunshot was so loud, the recoil was so violent, and my close-range aim was so far off was ultimately solved by some head scratching, a little reflection and discussion, and a liberal dose of metal detector.

I wound up digging up two relatively unmarked bullets from the spot where the buck had been when I fired. I did not pay proper attention to what I was doing and apparently loaded my rifle with two Pyrodex sticks and a projectile the night before the hunt — and then loaded it once again the next morning.

Being inattentive and in a rush, I committed a really dangerous and bone-headed error. I am extremely lucky to have not been maimed or killed in the process. A banana-peeled barrel is the usual result of something like this.

It is an absolute testament to modern barrel technology and metallurgy in general, and to the strength of TC Encore barrels in particular. There was a progressive discharge of first one charge, followed by the second discharge that threw my aim way off to the left and down.

Lesson learned: Always pay attention to what you are doing when dealing with issues of gun safety — especially where bullets and powder are involved.