There’s plenty of squirrel-hunting action in the rolling hills of the Kisatchie National Forest — if you know where to look and how to get into position.

Squirrels!

Here?

Was I really going squirrel hunting? A squirrel would have to pack a lunch to make it here. It was nearly solid pine trees — tall straight pine trees. Maybe 1 in 5,000 trees was a scrub oak or a stunted, gnarly magnolia.

The drive north from Interstate 10 toward DeRidder had lulled me. Agricultural lands gradually gave way to forest lands. The gentle hills were covered with a green mantle of trees.

It was beautiful.

Only when I turned off Highway 171 onto Highway 10 was I jolted to reality. The trees were all pine trees. Oh boy!

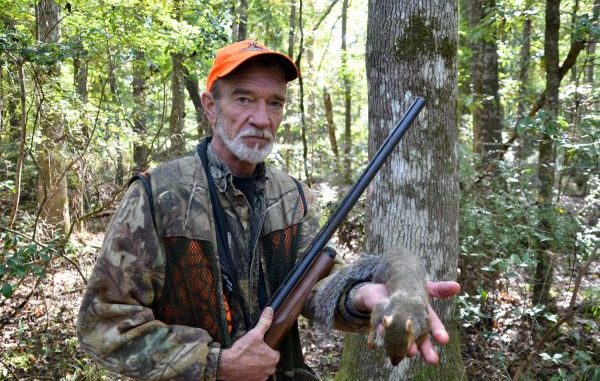

Bob Childress was right where he said he would be, puttering around outside his 30-foot Allegro Star motor home parked in a Kisatchie National Forest campground. Hooked behind his motor home was a trailer with a 400 cc Suzuki ATV onboard. The latter he uses to run the trails and roads of the national forest, chasing squirrels and deer.

His lean and craggy face broke into a broad smile when I pulled up.

“Welcome to Kisatchie National Forest, a squirrel hunter’s paradise,” Childress said.

I couldn’t wait to ask him how we were going to kill squirrels in pine trees.

The 56-year-old DeRidder native owns his own business, Bob’s Automotive and Muffler, and so has the flexibility to hunt and fish often. He explained the area while he chopped peppers and onions for his famous squirrel and gravy, which he was planning to cook on his outdoor cooker for supper.

“The national forest is open access — no leases,” Childress said. “If you see a pretty (creek) bottom, you just go in. The bottoms are beautiful old-growth hardwood trees, and there is a lot of land with a lot of bottoms.”

So we weren’t going to hunt in pine trees after all.

“Hunting is not very crowded, especially after the first few days,” he said. “Squirrel populations are high because few people hunt them. There is a mix of squirrels: fox squirrels, as well as cat (gray) squirrels. The foxes are in the smaller drains or on the edge where pines and hardwoods meet.”

He said reaching these gold mines of squirrels isn’t difficult.

“It isn’t rocket science to get around Kisatchie. It has good roads, and you can also use designated Forest Service roads,” Childress said. “Any halfway good map shows the creeks, and you just take a road to a creek crossing.

“Any major creek holds quality hardwoods — and lots of squirrels. The creeks will meander. You will find spots with only a narrow band of hardwoods on one side, and then around the next bend will be a big area.”

Squirrels in the bottoms have a choice of foods: pin oaks (aka water oaks), dogwood, white oak, magnolia, beech, hickory, ash — and lots of pine trees mixed in.

“Don’t ignore pines,” Childress cautioned. “They eat the seeds from pine cones.”

Childress explained that the huge national forest is not just friendly to squirrels, but to hunters as well. Tent campers can camp anywhere. Those with trailers and campers have access to multiple designated campgrounds.

The area in which we were camped and would be hunting was the Vernon Unit of the Calcasieu Ranger District of the Kasatchie National Forest. The unit was snuggled up next to and just south of the U.S. Army’s Fort Polk (much of which is also open to hunters).

Over one of the best squirrel suppers I have ever eaten, the veteran hunter explained that late-season squirrel hunting is different than hunting in October and November. The loss of leaves off the trees is both an advantage and a disadvantage.

A hunter can spot squirrels farther away, but squirrels can also see the hunter from a longer distance and hide. Also, by that time of the year, squirrels are spending much of their time on the ground, foraging for mast — like acorns — that has by then fallen from the trees.

“Because they can see you better than earlier in the season, you have to learn to slip through the woods quietly and slowly. Move when they move” he tutored. “Sometimes it is best to just sit and wait for them to come to you. You almost ‘deer hunt them.’”

He said there’s hunters also benefit this month because it’s breeding season.

“A big late-season advantage is that squirrels start to rut in December. They act funny, and you can rack up on them. Three or four males will fight over a sow coming into heat. They are funny to watch. They are easy to kill because they don’t pay attention to anything else,” he grinned.

No matter what part of the season Childress hunts, he said he sits or stands a lot and watches for movement in the trees.

“Squirrels will see you come in and freeze up,” he said. “After you sit five minutes, they start to move and you can slip up on them.

“Good eyesight is the most critical thing. Don’t look for a squirrel: Look for any movement that’s out of place. You see most of it with your peripheral vision. It’s a learned skill and comes with practice.

“Hearing is important too, especially when there is no wind. You can hear them gnawing on a hickory nut and you can hear the cuttings fall. Listen for rustling leaves and swishing branches too.”

Dawn the next day found Childress walking downhill from a Forest Service road into a creek bottom. The woods smelled good. A storm the night before dampened the leaves and made walking quietly easier. As he descended, he moved from pure stands of pine into more and more hardwoods.

The closer he got to the bottom the slower and more deliberate his steps became. The agile, fit man avoided stepping on twigs and never brushed limbs out of his way, preferring to silently duck them.

As he predicted, Childress spent much of his time squatting or standing still, slowly and intently sweeping his surroundings with his eyes. When he spotted a squirrel, his movements became distinctly more predatory, stalking the hapless rodent like a cat.

The stalk was inevitably punctuated by the booming katoom of his 12-guage shotgun, followed by the distinctive chi-chink of another low-brass No. 7 ½ shotshell being pumped into the chamber.

When Childress dropped a squirrel, he never moved immediately to pick up his prize. Rather he stood stock still and continued to scan the area.

“Lots of times several squirrels will be in one spot,” he explained, “and moving will spook the others.”

Every movement and decision the gray-grizzled hunter made had a reason. He ignored nearby trees, assuming any close squirrels had been spooked. Instead he looked in the distance.

“Looking at close trees is a common mistake of less-successful hunters,” he whispered, “although sometimes one will just pop out up close after I stop a while.”

He paid a great deal of attention to hiding himself. Less-experienced squirrel hunters naturally tend to gravitate to open, park-like patches of woods. Childress invariably opted to circle around open areas and moved through areas with lots of understory trees and shrubs that hid his movements. At the same time, he stayed out of dense thickets that made sight-hunting difficult.

He also avoided moving through sunny spots, knowing that the bright light of the sun would highlight him. He moved only enough to give him a fresh view of the woods, and when he stopped he shifted his body so his face was in the shade so he could see better.

The squirrel hunt was punctuated by other sights and sounds. He spotted a doe and fawn within gun range, and watched them until they loped off.

“On a different day, that would have been backstrap,” he quietly grunted.

Off in the near distance, the sounds of artillery fire on Fort Polk crumped. His ever-searching eyes spotted some water oak acorns on the ground, which he picked up and showed in his extended hand.

“Squirrel candy,” was his brief comment.

The morning’s hunt took Childress in a big circle to a spot farther down the Forest Service road he came in on. Back on the overgrown road, the veteran hunter’s pace picked up. He could hear biscuits and deer sausage calling him at the camp.

And he had squirrels to skin.