This time of year, the Mississippi River itself fills up with big, line-stripping redfish. Here’s how to put some in the box.

The Mississippi River’s nickname is the Big Muddy. It’s well-earned.

Take a peek at the river south of New Orleans in March, and you’d swear you could walk across it. There’s a lower percentage of soil in the average household garden. Visibility is roughly comparable to the thickness of a gnat’s wing.

If someone told you your life depended on your ability to pull a redfish from it, you’d kiss your wife and kids goodbye. It would be hopeless.

A blue cat? Maybe. But a redfish? Never.

That’s in March. But jump ahead six months on the calendar, and check out the same river. Even up around the Crescent City, it’s low and slow and green and clean.

For a significant portion of the year — much of the summer and all of the fall — the river could have an entirely different moniker: the Big Salty.

From New Orleans south this time of year, the Mississippi River is saltier than a bag of Ruffles.

That’s because the climate in the Plains and Midwest undergoes an annual, seasonal drought in the summer and fall, which limits the amount of rainwater entering the Mississippi and its feeder rivers and creeks.

Last year’s drought was especially acute, caused by a high-pressure system that formed over the Baja of Mexico and moved over the southern plains in mid-June. It stuck around through July and August, drying out crops and causing the deaths of 82 people from the resultant heat wave.

Since there was no rain on the plains, there was nothing to feed the big river, and she fell below 5 feet at New Orleans’ Carrollton gauge in June. It was unusually early, but after the record-high river of 2011, it was a welcome omen of the coming fishing action.

Capt. Dennis Bardwell had a front-row seat to the change. The river stayed low throughout the summer and fall — even threatening New Orleans’ drinking water — and got so low, slow and settled that visibility was not unlike that found on calm May days at the rigs just off the coast.

When that happens — when the river falls below 3 feet and loses the energy to support the bajillions of tiny grains of sediment — the redfish action gets so easy, it’s silly.

“We’ve got one spot where it’s every cast,” Bardwell said early in the morning last September as we were pulling out of Venice Marina. “We’ve got to beat everybody there.”

As we made the run through the Jump, the eastern horizon was just beginning to brighten, and the bumpy pass was abuzz with the comings and goings of crew boats and shrimpers, all either starting the day or getting ready to punch out after a long night.

We turned in the river and ran along the west-bank rocks. Constant traffic makes sure the river is never calm, but Bardwell ran hard when he could and came off plane whenever the wakes got ridiculous.

A very light breeze trickled in from the east, holding the promise of fall weather to come, but still a little muggier than the “good-feel air” of October.

In mere minutes, we were turning into the mouth of the West Bay Diversion, the cut in the levee that is producing so much land and working so well that the Corps of Engineers, naturally, wants to shut it down.

Bardwell motored up to a patch of dead roseau stubble that looked like it had been shorn by an Army barber. Other than that, there was nothing unique about the spot, and the only thing that indicated it would hold fish was some nervous bait near the shoreline.

“This is it,” Bardwell said. “If it’s anything like it’s been, we’ll have our limits in no time.”

But apparently it wasn’t like it had been. I had to make four casts before getting a bite from a big, line-stripping redfish.

“The fishing’s not good in Venice right now,” Bardwell said sardonically. “It took us four casts to catch one.”

That fish was quickly followed by several others, but we purposely stopped short of our limits so Bardwell could demonstrate how good the fishing gets in the Mississippi River itself during the fall.

Pulling up to a marsh spot and catching reds one after another is certainly fun, but many anglers prefer working a little more for them.

And the river definitely requires a little more effort. But keep in mind: Everything’s relative. The redfish action in the Mississippi is a whole lot easier than just about any other place on the planet.

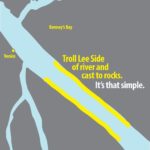

We motored out of the West Bay Diversion and cruised straight across the river to a cut in the rocks that opened into a canal. Bardwell picked up a short fish on the north corner, and then began to troll upriver. We threw gold spinners with Deadly Dudley Terror Tails right up against the rocks, and slow-rolled them back to the boat.

Initially, I retrieved my lure too quickly. I was trying to keep it just under the surface to avoid contact with the rocks, and I was successful in reaching that goal — but I didn’t catch any fish.

Bardwell retrieved his bait much more slowly, and he was whacking them.

I slowed down, and my catch rate skyrocketed. A crucial key was casting right up against the rocks and beginning the retrieve before the spinnerbait fell down into the rocks.

“You’ve got to be able to target what you’re aiming for,” Bardwell said. “You’re hitting a rock just about every time you’re making a cast. Most of the redfish are hanging right with the rocks, and as soon as it comes off the rocks, they hit it.”

It was an absolute blast, and the water was so clear we could easily see the reds 4 feet below the surface as we fought them. Many of the hooked fish came in with friends; either Bardwell or I would cast into the fray and immediately hook up.

“The last week and a half, it’s been all five or six reds, all the same size, running together,” he said. “It’s unbelievable to watch how they react trying to take that bait out of the other one’s mouth.

“You’re able to see 4 feet deep with the fish coming in, just like at the Causeway. You know how you catch a trout at the Causeway — he’ll be by one of the pilings and before he comes up, you see that mouth open? Well, the reds are doing that right now in the river.”

The action fishing this way definitely isn’t constant, but it runs in spurts of activity that make you forget all about the slow moments. Surely, if you go 15 minutes without catching one, you should pick up the trolling motor and power up to another stretch of rocks.

Bardwell said some stretches, for no identifiable reasons, are better than others, and he does what he can to be as efficient as possible in those areas.

“When you catch one, try to mark out a willow tree or a particular rock, and throw to it again because they’ll pile up on one spot,” he said. “It’s not like in the marsh on the grass where you can just sit there and catch them one after another, but you can definitely catch a few from one spot.”

Bardwell’s go-to bait for catching reds in the river is a gold spinner rigged with a blue moon/chartreuse Deadly Dudley Terror Tail, but a variety of other lures are successful including chartreuse Rat-L-Traps, crankbaits and soft plastics rigged on 1/4-ounce jigheads.

The fish definitely aren’t picky.

“Right now, you could throw bottle caps, and they’d hit them,” Bardwell said.

The fishing in the river proper is best when the level at New Orleans’ Carrollton gauge is 3 feet or less. It also improves after the passage of the first cool fronts in September knock the water temperature down a few degrees. As that temperature decline continues, other species join the redfish.

“The water in September is still in the 80s,” Bardwell said. “As it cools off, the trout will start moving in more.”

Flounder and stripers also get more active as the season progresses and the water cools.

“The great fishing will go into November, for sure,” Bardwell said.

The river usually makes its annual jump around Thanksgiving, although sometimes it’s not until mid-December. When it does jump, the action in the river is over — even if it jumps up and falls again.

But we’ve got several weeks of incredibly good fishing to go before that happens.

Head out of Venice this fall, and your favorite nickname for the Mississippi River will be Big Red.