The bass action near the tiny town of Caernarvon takes anglers back to a bygone era.

What must it have been like to fish for bass in Louisiana’s fresh and brackish marshes a hundred years ago, when the Mississippi River regularly cut crevasses and spilled its nutrient-rich load into the already fertile wetlands? Terry Cockerham has a clue.

For the last decade, the 42-year-old angler has spent most Saturday mornings towing his boat 90 minutes from his Tickfaw home to a small backdown ramp in the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it town of Caernarvon.

He just can’t stop coming because the bass fishing there isn’t much different than it was when Louisiana Indian tribes were the species’ No. 1 predator.

The trip back in time comes courtesy of the Caernarvon Diversion, a gated break in the river levee that is capable of diverting 8,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) of fresh, power-packed river water into the canals, ponds, bayous and lakes in western St. Bernard and northern Plaquemines parishes.

Although the diversion seldom runs beyond 4,000 cfs, it still packs quite a wallop, and has energized the Caernarvon area, creating one of the finest bass fisheries in the Bayou State.

“Compared to anyplace else within a two-hour run from my house, this has the best fishing,” Cockerham said while working a Wooly Hawg Craw in a Caernarvon dead-end canal on a recent trip with his fishing partner, Mike Graves.

A steady northeast breeze washed undulating waves of motion over the wire-grass prairies deep in the marsh and bent the tips of the barren mung bushes along the canal’s spoil banks. The sun pierced unhindered through a high, blue sky, trying with all its might to warm the winter-chilled air and water.

These were clearly not ideal conditions, but Cockerham and Graves were as undaunted as they were successful.

“A north wind really isn’t a bad wind here,” Cockerham said. “In fact, we kind of like a north wind because it makes the fish bite aggressively in many of the areas we fish.”

As if to prove his point, Cockerham moved his left foot forward, bent his left knee and lowered his rod tip, coiling for an upward explosion. The bass felt the sting in its lip, and charged out of the grass bed, Cockerham’s rod pointing everywhere it went.

A few cranks of the reel brought it to boatside, where the veteran bass angler stuck a thumb in its mouth and claimed his prize. It was a 2-pounder — nothing earth-shattering, but it would have been a solid weigh-fish on tournament day. No money was on the line this day, so Cockerham yanked the hook out, held the fish up to admire it a moment, and then set it free.

Two-pounders are the average, but bigger bass always lurk in the Caernarvon canals, according to Cockerham, who, along with Graves, is a member of Southern Bass Anglers, a Chalmette-based club.

“You really feel like every bite here could be a 5-pound fish,” Cockerham said. “We had one guy catch a 6-9 in a club tournament last year, and there was an 8-pounder caught in an evening tournament.”

Cockerham’s personal best was a 7-pounder that he caught in Creedmore Canal — an area that seems to have lost its productivity in recent years.

“Creedmore used to be our first and last stop of the day,” he said. “It used to be nothing to catch 30 or more fish in that canal in a day, but now, you can’t catch anything there.”

A couple of years ago, Cockerham took a bass pro into Creedmore who theorized that the dissolved oxygen in the canal had become too low to support bass. Cockerham thinks he knows why that may have occurred.

“The hyacinths were so thick in there three or four years ago that you couldn’t even get in there for an entire year,” he said. “Then they all sunk down and decayed. Before then, it was nothing to catch a 3- or 4-pounder in there; now, you can’t catch anything.”

Although they’re not overjoyed about the situation in the Creedmore Canal, Cockerham and Graves aren’t overly distraught because there are so many other options in the area that continue to produce fish after fish after fish.

Some of their favorites include Canal Marine, Lost Lake and Caskett Bayou near Spanish Lake. Their points of focus this time of year are dead-end canals.

“I’ve got two patterns; they’re very simple. In the summer, I fish lakes, and in the winter I fish dead-end canals,” Cockerham said. “I’ve tried fishing ponds, but I’ve never had success in the ponds. Other guys do, but it all boils down what you have confidence in, and this time of year, I’ve got confidence in the dead-end canals.”

The dead-ends provide protection for fish and fishermen from the relentless winds that seem to always blow during the cold-weather months.

But even in the protected canals, there will inevitably be a windward bank and a lee bank. Cockerham and Graves work the windward sides with Baby Minus-1 crankbaits and, secondarily, tandem willow/Colorado spinnerbaits.

“When the wind is wailing, they’ll nail a crankbait. You crank that Baby Minus-1 crankbait, and it just ticks the top of the grass. That’s when the bass crush it,” Cockerham said.

The anglers said that any color-combination Baby Minus-1 works as long as chartreuse is the predominant hue.

On the lee sides of the dead-ends, the anglers will work soft-plastic baits, especially Yum Wooly Hawg Craws, Yum tubes, Gilraker worms, Baby Brush Hawgs and, beginning the end of February, lizards and tubes.

But no matter whether they’re fishing crankbaits and spinnerbaits on the windward sides of the canals or soft-plastic baits on the lee sides, the anglers always fish out their casts because the submerged grass often grows very near the center of the canals, and that’s frequently where the bass hold.

“Sometimes there’ll be a double grass bed — one growing close to the bank, and then one farther out with an open area between them,” Cockerham said, explaining that other areas will have a thick grass line near the bank with isolated stalks and clumps growing toward the center of the canal.

“Once you figure out where the bass are (in relation to the grass), you can really catch a lot of fish,” he added. “There’s no structure out here, so the bass are all relating to the grass one way or another.”

Since the anglers are focusing their efforts on dead-ends, tidal conditions aren’t very important, but they do like fishing dead-ends that have run-outs leading into them and the wind-blown current they provide.

“With a north wind, the water will be boiling through those cuts,” Cockerham said. “The fish will stack up at the mouths.”

But too much north wind is not a good thing, Cockerham explained, because it blows the water out and makes the fish extremely close-mouthed.

“If it’s shallow, forget about coming here,” he said. “We’ve never caught fish on low water. At one of our club tournaments, we had 12 boats fish, and the water was so low that a total of four fish were caught. There may be people who can catch them in low water, but we can’t.”

But when winds aren’t extreme, a northerly breeze can work in an angler’s favor. Such was the case during one of the anglers’ club tournaments in late December.

“We started culling at 8 a.m., and weighed in 17 pounds,” Cockerham said. “Everybody caught 20 to 25 fish apiece, and 19 pounds won it.”

On that day, Cockerham and Graves worked one small dead-end off of Caskett Bayou.

“We’ll come to a spot and fish it all day waiting for it to get right,” Cockerham said. “If we know there are fish there, we’re just going to work them until they bite. You’ve got these guys who spend all day running around looking for feeding fish. If we have confidence in a spot, we’re staying put. Fishing, in my opinion, is about 90 percent confidence.”

Graves agreed.

“If we have confidence in a spot, there’s no reason to move,” he said.

That’s even more true when the Caernarvon Diversion is open and running. The Big Muddy got its nickname for a reason, and when that water-carried suspended sediment inundates the area, the clean dead-ends hold the lion’s share of the bites.

“The diversion muddies the water, and while it’s on, you’ve got to find clean water,” Cockerham said.

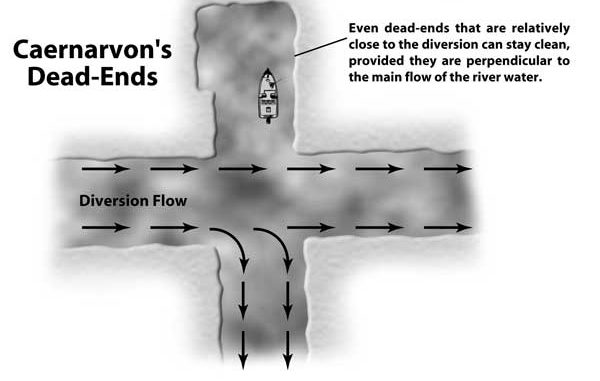

That frequently means traveling as far away from the diversion site as possible, but not always.

“At the Crow’s Foot, even as close as it is (to the diversion), the backside a lot of times will stay clear,” he said.

That’s because the fast-moving water coming through the diversion will often “pass up” certain dead-ends without eddying any water into them.

But it’s not only muddy water that’s coming through those gates, it’s also frigid water that only days earlier was likely in its frozen state somewhere in Missouri or the Midwest.

“The water temperature drops so much (when the diversion is running). The Big Mar is probably 40 degrees right now,” he said in late December.

That makes locating clean water even more crucial because it’ll warm much more quickly than dirty water, and it probably hasn’t had much influence from the diversion in the first place.

Cockerham and Graves find the dead-ends around Canal Marine to be consistently clean and relatively warm, even when the diversion’s open.

Once the diversion’s gates are shut, the fishing throughout the entire area goes through the roof, according to Cockerham.

“When the diversion’s turned off, the water clears up quick,” he said. “It’s like turning on a light switch for those fish. They go crazy.”

That’s especially true this time of year when the fish are in their full-fledged spawn.

“From the end of February through early April, that’s when we catch our heaviest fish,” Cockerham said. “You don’t really see them on the beds, but you can tell the fish are spawning because the sizes go up.”

This is the time when the pressure on these fish really goes up, when, it seems at times, everyone in the state of Louisiana who owns a bass boat is fishing Caernarvon on an average Saturday.

Cockerham owns Service Glass in New Orleans, and stays busy during the week, so he’s restricted to fishing the weekends. He’s seen the pressure skyrocket in the Caernarvon area in the last 10 years, particularly since a public launch ramp opened on Highway 39.

“We used to not see any boats all day,” Cockerham said. “Now there are boats everywhere, and the parking lots are packed.”

As an example, Cockerham mentioned his favorite dead-end near Caskett Bayou, which is no more than 100 yards in length. During their previous weekend’s tournament, five boats in addition to theirs plied the grass beds for bass bites.

To avoid the crowds at the public launch, Cockerham and Graves pay an annual fee to use the gated Delacroix Corp. launch adjacent to the public ramp.

“The pressure’s bad every weekend through the year here,” Cockerham said. “It’s not seasonal like at Venice.”

Also, Cockerham believes that there are more people bass fishing in Southeast Louisiana than in previous years, and they’re getting concentrated into increasingly smaller areas.

“People used to go to the Chef or the Pearl River, but now, there aren’t any fish in the Chef, and all you catch in the Pearl River are small fish, so they all come here,” he said.

But Cockerham isn’t complaining. Caernarvon seems to be holding up rather well under the stress. Anglers continue to come because the fishing is so consistently good.

“Really, your best bet is to come here,” he said. “Last year during our club tournaments here at Caernarvon, there was only one time out of eight tournaments that I didn’t catch my limit.”

Almost as good as a hundred years ago.