When Venice’s shallow-water reds turn a blind eye to your offerings, travel a little farther north.

Spring inshore fishing can be such a tease. Specks are ready for their reproductive business, but extreme changes in the weather make fish extremely mobile, rendering even the most up-to-date information obsolete.

But that compares little to the games redfish play as they ease into the warm-weather pattern. Reds are more than willing to mass in the shallow ponds and show themselves in all their bronze glory, but getting them to bite is an entirely different matter.Curiously, this behavior can cease with a simple change in location, something I painfully found last year.

It was a beautiful April morning on the water around the Wagon Wheel north of Venice. I’d found everything I had remembered about the area the year before: bait, a variety of freshwater grass, swarms of carp, the first of the season’s giant alligator gar and, of course, plenty of cruising redfish of up to about 7 pounds.

Along with the visual buffet line came the frustration of being refused again and again.

Even in the patches of aquarium-quality water in stark contrast to the Mississippi River-stained majority, the fish nonchalantly turned their noses at jigs, jerkbaits and a variety of flies.

This one particularly hurt. You know the dynamics of the delta allow for areas of water looking good enough to drink, but finding it can weaken the knees and make you immediately look over your shoulder to make sure no one else is in on your secret.

The fish became visible far from casting range, allowing for perfect positioning and all the stuff they teach in Florida and we seldom have time for here.

Sunburned and trying to enjoy the memories of the day on the ride home, I spied a flats boat from the Empire bridge turning the corner at Delta Marina.

You don’t see many of the vessels with “engine covers” — the most common guesses of what a poling platform is — down here, so I lurched to the right lane to satisfy my curiosity.

The bearded face of Capt. Bryan Carter was instantly recognizable, and we chatted about the day’s proceedings. I was hoping to commiserate, but Carter spoke of great action he’d enjoyed that day and days previous.

Any doubt about the common and likeable tendency for exaggeration was quashed when Carter’s customer for the day chimed in and told a similar story.

“You wouldn’t mind doing a story on your area, would you?” I asked, half expecting a polite refusal.

“Not at all. Most people couldn’t even think of getting back where I’m fishing,” he said.

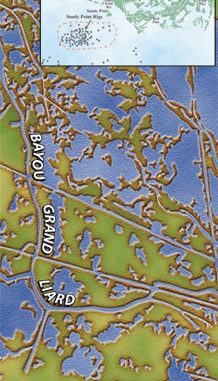

Where Carter was fishing is the vast network of ponds on either side of Bayou Grand Liard, northeast of the fresh grass ponds around the Wagon Wheel, Red Pass and the High Line Pond.

Accessible equally from Venice and Buras, these ponds are more typical of the salt marsh bordered mainly by Spartina grass. But to call them accessible would be misleading.

“These ponds are extremely shallow to begin with, and since the predominant tide in the early spring is still a low one, you need a shallow boat to get in there and effectively fish them,” Carter said.

Additionally, Carter says the best time to fish them is on a low tide that has just begun to rise as opposed to the high and falling tide favored by most in the summer and fall months.

“The rising water tends to bring fresh bait onto the flats,” he said. “This is the time of year when the mullet begin to show up in the ponds. Of course, we’re not really talking about the extreme low tides you get every now and then.

“When you’ve got really low water, the fish will move onto the oyster reefs in the open water around here.”

There are few things as pretty as seeing a redfish tail tip up from slick-calm water as he sifts through the bottom for food. But tailers are few and far between in Louisiana, except for the occasional flip along a shallow shoreline as a fish changes position.

“Most of the true tailers are found on top of the oyster beds. There are lots of places for food to hide amongst those shells,” said Carter. “There is so much food in the form of finfish around these waters that there’s not a whole lot of need for the fish to tail.”

Carter says that’s one of the reasons Louisiana fish, particularly those in the delta, are so healthy. The protein-rich diet of mullet, pogies and even mud minnows (cocahoes) is so prevalent that they concentrate much of their feeding efforts in cruising likely areas and picking off baitfish instead of somewhat inefficiently grubbing through the muck for a meal.

“Of course, the water is so deep in many of the ponds — not really the ones we’re talking about — that a fish could be tailing and you’d never know it.

“The fish that you really see tailing are the ones in the big schools. We don’t really get those big schools this time of year. It’s a lot of singles and little bunches of fish.”

The fish that Carter does see this time of year are those that are slowly cruising through the water without making a ripple even though they’re almost brushing the bottom with their bellies.

“You don’t get a lot of movement from these fish early in the year. The water is still a little cool for them to be ‘pushing’ or busting bait,” he said.

“What we’re looking for is a slowly cruising fish just under the surface in full view. That’s why I look for the clearest possible water. You don’t get a whole lot of clues as to where these fish are going to pop up, regardless of how shallow it is.

“The fish’s diet this time of year is mainly finfish, whether it be mullet or those tiny baitfish that you see jumping ahead of a fish. But everything is slower until a certain point in the spring, and even when a fish eats, it doesn’t give much of a clue as to its location.”

An important part of the equation in choosing which ponds to work is to find those that have a constant flow of water.

“I like what I call ‘two-way’ ponds, those that have openings on either end. This gives the pond a constant flushing of water, regardless of the tide,” said Carter. “You won’t always find the fish on the side where the water is entering the pond, but you do always have that situation except when the tide goes slack. I don’t like those round ponds that just end.”

Though there are plenty of times where fish will relate to the shoreline — early spring is not necessarily one of them. Carter says that during low water, the shorelines will be largely inaccessible. Finding a flat in the middle of the pond, where water exchanges from either end, is ideal for spotting cruising and feeding fish.

Conversely, says Carter, is fishing off of the shoreline when the water is high enough to flood the grass on the shoreline.

“Those fish will pull off the shoreline when the water is high for some reason,” said Carter, reasoning that perhaps the gently sloping bank doesn’t allow the fish to actually get into the grass.

As far as lures are concerned, Carter has three favorites, which are time-tested for this time of year. Each mimics a different bait species, though a few can serve as utility imitators.

“The EP Slider is one of those flies that can be both a finfish and a shrimp imitator,” he said. “It’s pretty long, and it’s got a lot of movement in the water. Its weed-guard keeps it out of the grass, and it’s got heavy eyes to get it down to the fish. It’s supposed to imitate a mud minnow, I believe.”

The shape of the EP Crab — the EP stands for Enrico Puglisi, a fly tier from the Northeast — is what makes it a solid producer.

“It’s got a real good profile in the water, and it’s got a good hook and a good overall color,” he said.

Tan may not seem like a sexy color, but Carter says the tan or a darker shade is best when crab patterns are concerned. When fish are as focused in on eating a replica of such a specific bait species, it’s best to go as natural as possible.

The Waldner Spoon Fly, on the other hand, comes in a wide variety of colors, which the tier swears makes a big difference in certain conditions.

“A darker shade such as purple or even black is best for those sunny days,” says Rich Waldner, who says his popular pattern is more of a simple attractant rather than a specific imitation. “When it clouds over, the gold and the chartreuse come through.”

Waldner experiments heavily with his favorite flies by spending quite a bit of time plying the Venice area as well as the water around West Pointe a la Hache near his home just north of the elk farm on Highway 23.

Another productive pattern is a Clouser minnow colored by purple and gold hair, and aptly named the Mardi Gras Mamma. It tends to be a better producer in the cold-weather months when things slow down.

“The spoons are fantastic for pulling through the grass, not necessarily that thick, scummy grass — nothing gets through that stuff — but the thinner coontail,” Waldner said. “You can throw it ahead of the fish and not worry about putting it exactly where it needs to be so that it won’t hang up.”

The Clouser is a better pattern for working fish that need things a little slower.

All of his flies are tied to relatively heavy 20-pound tippet, backed up by lengths of 30-, then 40-pound sections making up the 8-foot leader. Twenty-pound test might seem a bit extreme, but Carter says that as long as the fish don’t mind it — and they seldom do — the stout leader is necessary.

“I get some guys who are just not good casters, and no matter how good the fish are biting, they might only get a few good shots. And if that hook-up breaks off because it’s nicked on an oyster shell, that’s obviously not a good thing,” says Carter. “Besides that, I don’t like to lose flies or fish.”

So, if you’ve got the boat to do it and can tear yourself away from the aesthetics of the freshwater fauna to the south, the marsh in between the last two stops along Highway 23 can be a good bet to do more than just look at fish.

Capt. Bryan Carter can be reached at (504) 329-5198.