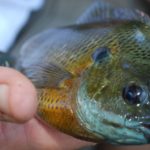

There are certainly bigger fish to be caught, but there aren’t very many that are as fun as bream. Especially when thick bull bream are guarding their nests.

The broad-shouldered man actually tiptoed when he moved around in his boat. “Being quiet,” he explained, “is real important when you are fishing for bull bream in shallow, clear water.”

We were indeed in shallow water — 2 to 3 feet deep. Through the tea-colored water, multiple, round plate-sized bream beds could be seen as dark blotches on a lighter bottom. A resident male bluegill was likely hovering over or around the nest, guarding it against intruders that could eat his eggs or young.

These bold males, called “bull bream” by bream-fishing lovers will attack anything, especially anything resembling food that intrudes on their space.

Aggressive they are; stupid they are not. Loud noise or a sloppy approach will send them into a sulking funk or scuttling to deeper water.

The day was hot enough to burn a wet frog. In other words, ideal bream weather. When Freddie McMullen, my fishing partner for the day and the man at the helm of the 23-horsepower Mud Buddy surface drive engine, chopped his way through the dense aquatic vegetation and into of a grove of cypress trees standing in the water, I welcomed the shade with relief.

McMullen quietly eased his trolling motor into position and moved the boat to within casting distance of the spot he planned to fish. With one of his ultralight spinning rods, he began fanning casts to the front left and right of the boat. A bite or a catch from a spot prompted the next cast to the same place.

Bull bream bed up densely.

McMullen’s spinning rods are rigged with 4-pound-test high-visibility monofilament line.

“I use high-visibility line so that I can see it to tie it,” he joked.

On the business end of the line, McMullen ties a short-shank No. 8 Mr. Crappie hook. Above the hook is an oblong, slide-on foam cork set to keep the bait just a few inches off the bottom.

Slightly above the hook, McMullen crimps on two or three split shot weights.

“I like to start with three,” he said. “That way, when I lose one, I don’t have to stop fishing.”

The weights make casting easier and sink the bait quickly to the bottom. They also keep the oblong cork floating upright. When a bull bream picks up the bait, the cork will lay over slightly on its side, indicating even the subtlest bite.

McMullen carries and uses two kinds of bait. Like most bluegill anglers, he uses lots of crickets, but in addition he really likes using wax worms. The latter, he notes can be a little hard to find in some places, but he gets his at a bait shop on Bayou Desaird in Monroe.

Wax worms, he believes, catch more and bigger fish.

“But my brother Mike refuses to fish with anything but crickets” he noted. “I find that sometimes one catches more and sometimes the other.

“So I put both on a hook.”

McMullen’s face always seemed to be smiling, or at least grinning. But with every beautifully colored bull bream, his face broke into a beaming smile — like he was greeting a long-lost friend.

“Why bream?” I asked him. “They’re not the biggest; they’re not the most glamorous.”

He had a lot of answers for the question.

“Well, to begin with, there is a lot more action than with other kinds of fishing,” McMullen said. “And it’s a family tradition. It’s low-stress, and bream fishing is not done under dangerous conditions and in deep water.

“It’s relatively inexpensive compared to other types of fishing. It has dependable catches, especially compared to bass. With (bass), you can cast all day and catch nothing. Very rarely does that happen with bream.”

He paused, unhooked and dropped another fish in the ice chest and went on.

“The surroundings when you bream fish are beautiful,” McMullen said. “And maybe best of all, they are real good to eat and easy to clean.”

The man clearly knew his beans. He spread casts all around the boat to probe every inch of reachable water. He seldom let the bait sit still for long, retrieving it back to the boat with vigorous twitches and short pauses between them.

Strikes always came on the pauses.

When he cast near tree trunks, he always cast past the trunks and twitched the bait back to it rather than casting directly at the trunk.

He was comical, too. He muttered to himself while he fished, and he talked to the fish. He scolded himself when he missed a bite, and constantly coached the fish.

Every 15 fish or so, McMullen moved the boat with the trolling motor to fish a new area.

He was catching almost all big bull males because he was concentrating on bream beds. When he finally caught a female, he chuckled before throwing it back.

“That’s the kind ‘Road Kill McMullen’ would keep,” he said using brother Mike’s nickname, derived from his penchant for picking up road-killed wildlife and tanning their hides.

“He don’t throw none back,” he said. “He worked a deal with the cafeteria people in school: He gave them the fish he didn’t want to clean, and they gave him scraps for our dogs.”