Hunting picked up after spotty opener, guides say.

Sonar’s job is to show us the depth, composition and shape of the bottom below our boats and reveal suspended objects like fish. The basic principles governing how sonar works don’t change, but manufacturers keep developing neat, new ways to manipulate them that make units easier to operate and bring picture-like displays to screens that even new users can understand at a glance.

Still, many users prefer looking at a traditional sonar view to accomplish certain tasks, even though it takes a while to learn to interpret it.

Conventional sonar

Conventional down-looking sonar devices use a cone-shaped beam with 20 degrees being the most common beam angle. The cone’s narrow end starts at a sonar unit’s transducer and spreads to cover a circle on the bottom that is roughly one-third of the depth. In 30 feet of water, for example, the cone covers an area on the bottom that is roughly circular and 10 feet in diameter. Objects suspended within the cone are also detected by the beam. Displaying small objects in lifelike detail is a problem for these units because they have to convert everything within the cone’s three-dimensional area into the two-dimensional picture that appears on a unit’s screen. Simply put, this cone “sees” too much to present a picture-like display under all but ideal conditions.

You can often see objects outside the official boundaries of a 20-degree cone, even out to 60 degrees or so. This usually occurs at shallower depths but can also happen nearly anywhere in clean water over a hard bottom. A good way to think of the manufacturer’s stated cone angle is that you may see more water in a wider area under some conditions, but you should never see less.

One common misconception about the way a sonar screen picture is formed is that the transducer’s beam shines like a flashlight and somehow uses all your screen’s pixels to put together a constantly-changing, television-like picture of the underwater world. Actually, sonar simply measures the distance between the transducer and any object (including the bottom) that returns an echo and places a mark on the screen showing each object’s distance from the transducer at the instant of the sounding. Instead of presenting the actual depth below the surface of these objects, sonar indicates their distance from the transducer. That distance only equals actual depth when a target is directly below the transducer. Consecutive soundings appear on the screen one row of pixels at a time and combine with adjacent columns to form the screen picture.

Transducers commonly emit 20 to 30 sound pulses per second, and even at cruising speed the cone-shaped beam is moving slowly enough to allow different portions of the beam to hit different parts of a target, recording the target’s outline as a collection of different distance marks. These overlapping returns are the reason that fish appear as arches and submerged trees, and other objects are displayed in a sort of domed or rounded-off fashion.

New side and vertical imaging sonar

New units capable of picture-like displays must also follow the basic principles of sonar, but they avoid the rounded-off views caused by overlapping soundings by changing the shape of their transducer beams. Gone is the round cone: Depending on the model and operating frequency, they use multiple side-by-side beams to cover an area from 45 to 75 degrees wide (left to right), but only three to six degrees thick from front to back. As the boat travels forward, the transducer scans these razor-thin, fan-shaped slices of water with each sounding. The short front-to-rear measurement of each slice severely limits any overlapping of soundings, so when the columns or rows of pixels from consecutive soundings scroll across the screen they form a picture that is a much more true to life.

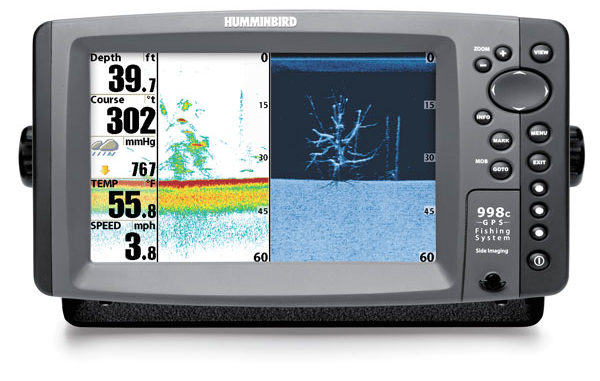

Both Humminbird and Lowrance now offer less expensive units that only look down (not to the sides) but still offer the picture-like display quality of the side-looking models. Humminbird includes a conventional sonar beam as well as its down-imaging beam in these units enabling them to present your choice of super-detailed or conventional sonar views. The more expensive side-looking units from both companies usually include down- and side-looking high-detail sonar and a conventional, down-looking mode.

Who needs which type for what?

Boaters and fishermen just learning to operate sonar will probably be perfectly happy with the newer type of high-detail unit. Those already used to conventional sonar may prefer to have a choice. Many will probably want to run the conventional mode while the boat is on plane and while fishing vertically with the boat at rest, and run the high-detailed mode while moving forward at 3 to 5 m.p.h., the most effective speed for the high-detail systems. Being able to use a split-screen view showing a conventional picture on one side and a high-detail view on the other can help longtime users of conventional systems learn to spot fish with the new technology. Fish often appear as small dots or short lines rather than the big arches they are used to seeing on the screens of conventional units.

Eventually, though, I believe that fans of traditional sonar will probably run the newer imaging modes most of the time. I can get great readings up to my boat’s 40 m.p.h. top speed with the high-detail side and down looking models from both Humminbird and Lowrance. I still find myself sometimes switching back to the traditional view to confirm fish sightings, but they say even a worm learns after four or five hundred repetitions, so there is hope for me.

Tuning tips for side scanning

A good rule of thumb when setting the distance ranges for the side-looking beams at any depth is to use no more than a five-to-one ratio. For instance, in water 30 feet deep, 30 x 5 = 150, so set the side ranges to look 75 feet left and 75 feet right for a total scan width of 150 feet. When using a conventional sounder, you always use the smallest depth range setting that puts the lake bottom at the bottom of your screen.

If you use a range setting that puts the bottom in the middle of your screen, you are wasting half of its pixel count and getting only 50 percent of the detail you paid for.

It’s the same with the side-looking ranges: the farther you set the sonar to see, the smaller important details look and the less likely you are to spot them. You also waste pixel detail if you set the side-looking beams to see well past where they hit the bottom. This is all common sense but it’s amazingly easy to forget these important details while playing with new technology.

Most side-imaging and high-detail down-looking units offer both 455 kHz and 800 kHz operation, and the two frequencies perform differently. 800 kHz gives you superior detail but less reach. It is probably best used in water less than a hundred feet deep, and its beams don’t “see” out to the sides at quite as wide an angle as the 455 kHz beams.

455 kHz offers a wider viewing angle and more depth penetration. Don’t be afraid to try both frequencies in any situation, though, because one might work better than the other when you least expect it. If you are in shallow water and want to look at the widest possible area, for instance, you should try 455 kHz because it offers a wider scanning swath at all depths. It can also be the best choice for spotting baitfish schools holding near the surface out in deep, open water for the same reason: The wider scan area lets you see the sub-surface schools farther from the boat.

The new breed of side-looking units is already popular among freshwater lake and river boaters, and the technology is gaining converts among saltwater users who don’t exceed the technology’s practical depth limits. Such units can still meet needs of deep-water boaters if they pick one with a conventional sonar mode that can take over in really deep water.