Love looking at the photos from your trail cameras? Why not take those photos and use them to help tweak your deer-management program?

Prairieville hunter David Ellis is like many hunters these days, setting up trail cameras on his hunting property near Natchez, Miss., to see if he has any monster bucks roaming the 160 acres.

But while he will pass them around to his friends, Ellis isn’t just interested in collecting a photo gallery of bucks — he’s using his trail cams to ensure he’s moving forward on the quality deer-management program to which he has committed.

“I want to know what shooters I’ve got and which deer will be shooters in a couple of years,” the dentist said.

He begins that process in August, using corn to attract deer to his trail-cam sites, and continues through at least mid September.

“I’ll throw bags of corn in a couple of spots and set up cameras to see what comes to them,” Ellis said. “I’m just kind of surveying my deer.

“It’s for me to catalog in my mind what I’ve got.”

Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks biologist Justin Thayer, who earned his graduate degree at LSU, said this is exactly how he and other deer biologists have been using trail cams since they were introduced.

“Before trail cams, we were looking for any reliable way to count or census animal populations,” Thayer said. “A deer count was done with spotlights; it literally was us riding around in the back of a truck at night counting eyeballs.”

That information was then extrapolated to make an estimate of how many deer were on a piece of property, and best guesses were made of sex ratio of the deer herd in question.

The introduction of trail cams revolutionized that process.

“They gave us an incredible tool that gave us the ability to see those pieces of information in action,” Thayer said.

He said biologists quickly developed an involved protocol in which cameras would be positioned to make pretty accurate catalogs of all deer on a piece of property, with the gold standard being one camera per 100 acres.

“You’re able to get population density, age structure and sex ratio,” Thayer explained.

Biologists can then make more-informed management recommendations to hunters.

But Ellis does more than just flip through the photos and count the number of does and bucks that live on his property: He studies the images until the characteristics of each rack are burned into his mind.

“Sometimes you see a deer and only have a few seconds to make a decision,” he said.

Those split-second decisions are important because hunters on Ellis’ property can’t just shoot nice bucks — they have to shoot really nice bucks.

“I’m trying to not shoot anything that is less than 140 inches, and nothing less than 4½ years old,” he said.

That means being able to distinguish between that fine 130-inch buck and a monster 150-inch deer quickly is critical. And that’s no problem for Ellis because he spends so much time examining every buck image he collects on his trail cams.

“When I see that deer, I immediately can say, ‘Oh, that’s that deer,’” Ellis said. “It keeps me from having to make snap decisions.”

Thayer, who is a big proponent of using trail cams to fine tune deer management, said Ellis is on the right track.

“You can print these pictures and share them with other club members,” Thayer said. “It’s hard for a lot of club (members) to share these photos, but that’s where you’ve got to go.”

It’s pretty easy for Ellis, since he is the landowner, but Thayer said passing around photos can result in allowing young bucks that show real potential to walk while mature shooters are taken.

“You can nickname them,” Thayer said. “Say a young buck has a crooked main beam, you can call him ‘Crooked Beam.’

“So when a club member sees that deer, he can say, ‘That’s Crooked Beam. I need to let him walk.’”

That brings in the second component of management using trail cams — aging deer on the hoof.

Ellis spends a lot of time looking at photos trying to make a determination of the ages of his bucks, which he is the first to admit is far from a science, but he is fairly confident he can determine which deer are exhibiting the highest potential and which are lagging behind.

“I’m pretty good,” he said. “I can tell the difference between a 125-inch deer and a 140- to a 145-inch buck.

“I feel like I’m within 5 inches.”

Aging deer on the hoof is even tricky, but there are distinct differences between a 1½-year-old or 2½-year-old buck and a 4½-year-old brute.

It’s an important part of the equation, Thayer said.

He said Mississippi State University research has provided a breakdown of antler potential for deer as they age.

For instance, a 1-year-old deer has grown only 26 percent of the rack it should develop at full maturity.

Antler potentials for other ages include:

• 2-year-olds – 44 percent

• 3-year-olds – 77 percent

• 4-year-olds – 92 percent

• 5- to 6-year-olds – 100 percent

That is invaluable information for the hunter looking to manage a deer herd with an eye toward producing quality animals.

“You can forecast the potential of your young deer,” Thayer said. “You quickly realize the 2½-year-old deer is your fully matured 150-inch buck.

“That deer’s got roughly 60 percent of its (Boone & Crockett) score potential left to grow.”

That means you can then ensure everyone hunting the property can recognize this buck and hold off on shooting it.

It also can work the opposite way, however, allowing hunters to pull the trigger on bucks that are unlikely to ever reach trophy or even quality levels.

“On the other end, you’ve got that 50-inch 2½-year-old, and we know that’s going to be less than 100 inches.”

Ellis said he’s used this exact approach, identifying some cull bucks that are now on his hit list.

Making all that work as it should, however, comes back to effectively aging and scoring deer from trail-cam photos.

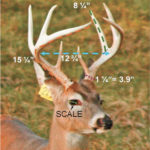

At least the scoring aspect of the job has been made easier recently with the introduction of a computer program dubbed “Buckscore,” which was developed to allow bucks’ racks to be quickly scored from trail-cam photos.

The program is arguably one of the most-important advances in the use of trail cams for deer management.

Buckscore allows any hunter to score a deer based on a trail-cam photo with a few simple clicks of a mouse.

“All you do is trace the antlers, and then the program does all the rest of the work,” developer Jeremy Flinn said.

The program allows users to choose the state and age (if known) so the scoring computation is as accurate as possible — and it nails the score pretty well.

“We found you can get within 5 percent of the actual score,” Flinn said. “There are plenty of deer in the 170-, 190-, even 200-inch range that I’ve scored within 2 inches.”

The program works best on deer looking directly at the camera and on photos taken from 45-degree and 90-degree angles. Scoring deer from each of these angles will narrow the gap.

“With the use of multiple photo angles, we’ve found scores come within 2½ percent of the actual score,” Flinn said.

That level of accuracy, which has been made possible by the use of penned deer Flinn and his fellow developers could then tranquilize and score, is a quantum leap in the real-world use of trail cams as management tools.

“Buckscore has added science to a relatively unscientific tool,” Thayer said.

And it’s a program that is so easy to use that the average hunter can quickly become adept at scoring deer.

This leaves only the aging component as a bit of best-guess, but that’s something researchers are now working on. When their work is complete, a new Buckscore component will allow users to age deer captured on trail cams. The aging component should be finished in January.

That will cap off the usefulness of the software from a management standpoint, taking all the guesswork out of management, Thayer said.

For instance, the program will allow hunters looking to truly up deer quality to combine all the pertinent information available — antler score, buck age, sex ratio, deer density — from trail cams to determine exactly how many does and bucks need to be shot.

And make determinations of exactly which bucks should be shot.

“For balance in the sex ratio of your deer herd, you’ve got to shoot a certain number of bucks,” Thayer said. “If you’re going to have to shoot some of the buck segment, then you’re going to want to shoot the inferior deer.”

Heard about a big buck kill? Know some details? Let’s talk about it at www.LouisianaSportsman.com.