Despite hurricanes and oil spills, the Atchafalaya River remains Louisiana’s greatest threat.

“The time for dillydallying with this great problem has passed; [federal officials] are far too dilatory in their movements, and take too long to devise ways and find means to avert the threatened danger, and rather incline to a plan that is entirely at variance with their printed opinions. . . [T]he people . . . must bestir themselves in their own behalf. The time for theorizing and talking is past; the time for action has arrived.”Sound familiar? How often in the past five years have we heard similar demands for government intervention? Louisiana has taken a beating in the 21st century with Hurricanes Katrina and Rita and the BP oil spill. And to our utter frustration, it seems that government officials are chronically slow in reacting to the disasters. Sadly, this is nothing new.

Take the above quote, for example. The author’s anger does not stem from coastal erosion or a hurricane or an oil spill; it does not even come from the 21st century — or 20th for that matter. This outburst was written 126 years ago, and the Atchafalaya River was the source of the writer’s frustration.

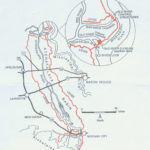

The Atchafalaya is unique. A distributary of the Mississippi, it flows out of the Big Muddy near Simmesport, and runs approximately 125 miles before emptying into the Gulf of Mexico near Morgan City. The Atchafalaya Basin, famous for being America’s largest swamp wilderness, stretches about 35 miles between Baton Rouge and Lafayette.

Because of the incredible changes that have taken place on the river in the last 100 years, some geologists refer to the Atchafalaya as the “phenomenon of the 20th century.”

Looking at the broad, turbulent river today, it is hard to imagine that once upon a time a person could almost jump across it. Reminiscing in a 1973 newspaper article, one man remembered, “[G]randma … said that back before the Civil War when she was a child growing up on the river, it was a docile little stream. Her story, passed down through the family, said the Atchafalaya was so small in places in those days that you could throw a log across it and walk over.”

The river’s transformation into a mighty waterway is yet another cautionary tale of man’s sometimes reckless interference with Mother Nature.

The Atchafalaya begins in the Three Rivers region, an area where the Mississippi, Red and Atchafalaya come together. However, the Red and Mississippi did not always merge there. They flowed along roughly parallel paths until about 500 years ago, at which time the Mississippi formed a large looping bend to the west that cut the Red River in two. This meander eventually became known as Turnbull’s Bend.

When Turnbull’s Bend was created, the upper part of the Red became a tributary of the Mississippi, while what had been the old Red River channel farther south became a distributary — the Atchafalaya.

The new Atchafalaya River soon dwindled in size because debris carried by the Red and Mississippi created a huge, 20-mile-long log jam at its head. For about 300 years, this log jam, or “raft,” acted as a dam and restricted the water flow into the Atchafalaya.

By the early 19th century, the Louisiana economy had come to depend on steamboats carrying cotton and other goods along its major rivers. Frequently, the federal and state government financed improvements to make steamboat travel more efficient.

In 1831, famed steamboat captain Henry Miller Shreve was given a contract to cut a new channel across the narrow neck of Turnbull’s Bend to straighten out the Mississippi so boats would not have to make the long voyage around the meander. Afterward, the old channel on the bend’s south side became known as Old River, and the Red River continued to flow into the Mississippi by way of it. It was through Old River that steamboats moved back and forth between the Mississippi and Red.

Soon, residents in the Atchafalaya Basin pressured officials to do more to open that river up to steamboat traffic. When the state refused to appropriate money to remove the log jam clogging the river’s headwaters, citizens decided to take action on their own.

A severe drought in 1839 dramatically lowered the Atchafalaya and exposed more of the raft (contemporary reports claimed the river got so low that people could walk across it on a 15-foot plank). Local residents set fire to the mass of exposed debris in the hope of burning it away, but all they really accomplished was the killing of thousands of alligators. While the fire did burn the raft down to the water line, it had no effect on the jumble of logs under the water.

Government officials then agreed to act and hired Shreve to finish clearing the log jam. This project, however, set in motion a chain of events that completely transformed the Atchafalaya.

For 300 years, the log jam had forced the Red River to flow into the Mississippi by way of Old River. When Shreve cleared the raft, it was though a plug had been pulled and the Red suddenly began discharging its water down the Atchafalaya. When the Mississippi overflowed during floods, even more water poured into the basin by way of Old River. In a short time, this huge increase in water volume scoured out what had been a minor stream channel and turned it into the wide, raging Atchafalaya River we know today.

Faced with an ever-widening river, landowners began building levees to try to contain it, but the banks caved in after every flood, and they had to keep moving levees, homes and buildings farther back. One cotton farmer living seven miles south of Simmesport was forced to move his house and store twice.

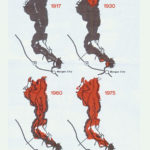

The millions of tons of sediment that were deposited in the basin every year also transformed the landscape. While the Red River has only one-tenth of the Mississippi’s water volume, it carries four times the sediment, and it was now shooting down the Atchafalaya channel. When the river flooded, these sediments filled in much of the backswamp and created new land that was soon covered in large hardwood forests.

In the lower basin, the sediments at first created deltas in the large lakes and then gradually filled them in. During the Civil War, Yankee gunboats patrolled Grand Lake and Six Mile Lake. One hundred years later, Grand Lake had essentially disappeared, and Six Mile Lake was rapidly filling in.

The new and bigger Atchafalaya dramatically changed the basin’s ecosystem, but that was not the most significant result of Shreve’s “improvements.” Water seeks the path of least resistance, and about every thousand years the Mississippi River changes course to find an easier route to the Gulf. The lower Mississippi has been in its present channel for about a thousand years, so it’s time for a shift.

The Atchafalaya channel is 190 miles shorter to the Gulf than that of the Mississippi, and it has a steeper grade. As a result, the Mississippi began trying to change course and flow down the Atchafalaya soon after Shreve removed the log jam.

Everyone at the time realized such an event would be catastrophic. Even people outside Louisiana kept a wary eye on the now dangerous Atchafalaya. In 1881, a Helena, Mt., newspaper reported, “The wayward Mississippi, according to the New Orleans paper, is giving very strong evidence of its intentions to desert the Queen City of the South and seek a new outlet to the gulf. It seems that the Father of Waters is rapidly cutting another channel, and that the entire waters of Red River and huge portion of those of the Mississippi are now flowing through the Atchafalaya. Unless they can be arrested it is not improbable that New Orleans may be lost in the near future stranded on a shallow stream.”

Over the next three years, federal officials studied the problem but took no steps to contain the Mississippi. When an 1884 government investigation predicted the Mississippi might change course down the Atchafalaya in two years or less, a frustrated New Orleans Times-Picayune warned the public of the looming disaster.

“The danger is immediate and threatening cause for national alarm. The water pouring down the Atchafalaya has already caused the shoaling for the Mississippi below the mouth of Red River, and as the flood of the Mississippi is deflected, this shoaling will increase … . The [Atchafalaya investigation] showed that stream more angry and turbulent than ever before. It had grown in every respect. One hundred feet from its entrance no bottom could be found at fifty-three feet. The river had increased its width; huge masses of land had sloughed off and large areas been swept away by undercutting currents … . This is the situation, and it is startling … . Every day lost now is a waste of valuable time.”

The Times-Picayune pointed out that it would cost as little as $12,000 to construct a sill across the head of the Atchafalaya to keep the Mississippi at bay, yet nothing was being done.

“Every day this work is postponed the danger is magnified, and the cost of remedying and preventing the deflection of the Mississippi increased. The commercial bodies of New Orleans should sound the alarm to the valley, and the valley through its representatives in Congress should insist upon instant action in this most important matter.”

The rivers were left unchecked, and devastating floods frequently occurred in the basin as more and more Mississippi water spilled into it. The flood of 1912 was particularly bad.

One reporter later recalled, “Grandpa Lindsey’s house was on stilts so high that I could stand under the house as a child. But the 1912 flood put 3 feet of water in the elevated first floor, forcing the Lindseys and their eight children into two small upstairs bedrooms.

“Mother recalls she crawfished off the front porch while the water was lower, but threw down her pole and ran screaming when she caught a water moccasin. At the height of the flood, she said she saw snakes swimming down the first floor hallway.”

The possibility of the Mississippi taking over the Atchafalaya channel had been discussed for nearly 100 years, yet officials seemed surprised when the threat surfaced again during the great flood of 1927.

An army engineer who inspected Old River reportedly observed “phenomena that led him to suspect the possibility the Mississippi was attempting to change its course through the Atchafalaya.”

Former Gov. John M. Parker, a flood-relief director, was quoted as saying that while it was not exactly clear what was happening, “we do know that something strange is occurring and we want to be prepared.”

Worried officials warned the people of Pointe Coupee Parish to be prepared to evacuate all women, children and the elderly in case the Mississippi did take over the Atchafalaya channel.

Fortunately, the 1927 flood receded without the Mississippi River changing course, but it still took more than 30 years before anything was finally done to contain it. The impetus was yet another study commissioned by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the early 1950s. This one predicted that if left unchecked, the Mississippi would divert down the Atchafalaya Basin by 1990.

Finally, after more than 100 years of “dillydallying,” the federal government began constructing the massive Old River Control Structure near Simmesport to keep the Mississippi River in its channel. Completed in 1963, it diverts all of the Red River and about one-third of the Mississippi down the Atchafalaya. Locks also allow boats to travel back and forth between the Mississippi and the Red and Atchafalaya.

During floods, control gates can be opened on the structure to allow more Mississippi water to flow into the Atchafalaya and thus relieve pressure on the levees downstream. The structure’s greatest challenge occurred during the flood of 1973 when the gates were opened to full capacity.

At the height of the flood, the entire dam began to shake violently, and engineers realized the roaring water was undermining the structure. A collapse seemed imminent, and officials warned the people of Morgan City to prepare to evacuate to escape what would be a catastrophic wall of water. Fortunately, tons of rock that were quickly dumped along the structure’s base stabilized things until the flood receded and permanent repairs could be made.

The flood of 1973 gave us a glimpse at how quickly rivers can change Louisiana’s landscape. So much sediment was carried down the Atchafalaya that spring that it created a new delta in Atchafalaya Bay. Sediment continues to pour into the area, and geologists estimate the entire bay will fill up within the next 50 years. In our younger people’s lifetime, marsh will cover what is now open water. The Atchafalaya Bay is one of the few areas of coastal Louisiana that is creating new land rather than having it eroded away.

If the Old River Control Structure had collapsed in 1973, the Mississippi River almost certainly would have diverted permanently down the Atchafalaya. If (or when) that happens, the consequences will make the hurricanes and oil spill seem like minor inconveniences.

It is estimated that about 70 percent of the Mississippi’s water would flow through the Basin. The Atchafalaya would be an incredibly raging river until a large enough channel was scoured out to handle the excess water.

This would likely weaken and perhaps even collapse all of the highway and railroad bridges across the Basin. Even if they survived intact, they would be closed for a lengthy period of time while safety inspections were completed.

With the loss of Highway 90 and I-10, interstate east-west traffic would have to be diverted to Highway 84 at Vidalia and I-20 at Vicksburg. The additional traffic on those roads would create a traveler’s nightmare, and increased transportation costs would drive up prices.

Morgan City and other basin communities would have to be abandoned, and the oil and gas wells, pipelines and canals would be destroyed.

In a replay of the BP disaster, the oil spillage would be immense, and it might take years to repair the damage. Such an interruption in the industry would also have an immediate impact on the nation’s gasoline prices.

To make matters worse, the increased sediment and fresh water would ruin the area’s oyster beds and shrimp industry, and commercial crawfishing and recreational fishing would be dramatically impacted.

Such a structural collapse would also devastate the lower Mississippi, where the river would shrink by two-thirds almost overnight. Constant dredging could probably keep open a channel deep enough to accommodate ocean-going vessels, but shipping might be interrupted during times of low water.

A more serious problem would be the effect a smaller Mississippi would have on Baton Rouge, New Orleans and the ecosystem. Because the river’s current would be greatly reduced, the Gulf’s salt water would intrude far upstream, killing the vegetation along the river bank and causing soil erosion. Within a relatively short time, the river below Baton Rouge would become a giant saltwater estuary.

Expensive levee systems might protect New Orleans and smaller towns from eroding away, but the communities and industries from Baton Rouge to the Gulf would lose their source of water. Underground aquifers would not be able to fill the need, and multi-billion dollar pipelines would have to be constructed to bring in water.

The implications of an Old River Control Structure collapse are so enormous it is difficult to wrap one’s mind around it. If you recall, we said the same thing six years ago about a direct hit on New Orleans by a Category 3 hurricane and an oil spill large enough to wipe out life in the Gulf of Mexico. Louisianians now have learned that such unimaginable disasters can take place — and in rapid succession.

We have also seen firsthand that the government seems unable to respond in a timely fashion to such catastrophes. How would it react to a collapsed Old River Control Structure? Hopefully, we will never have to find out. Hopefully, we have learned our lesson, and strong measures will be taken to keep the Mississippi River out of the Atchafalaya.

But I wouldn’t bet on it.