The rocky history of Toledo Bend Reservoir’s construction has been largely forgotten in the last 40 years of incredible fishing. However, the lake’s inception was a herculean effort that “took a miracle.”

“An almost forgotten historic site near Many (the Civil War’s Sabine Breastworks) is on its death bed. It will die slowly as it gives way to progress and surrenders to the waters of the giant Toledo Bend Reservoir.”

— Norman Richardson, The (Shreveport) TimesToledo Bend today is arguably Louisiana’s best-known bass destination, drawing anglers from all across the state and the nation to catch big fish and enjoy a reservoir that is now ingrained in the lore of fishing.

The communities surrounding the monstrous reservoir, both in Louisiana and Texas, depend on these visitors to drive their economies. In short, Toledo Bend is a godsend to this part of the world.

“It’s the engine. It’s what’s driving everybody,” said Linda Curtis-Sparks, director of the Sabine Parish Tourist Commission. “It’s the good fishing that attracts the tourists and the retirees.”

What might be a surprise is the fact that many local residents resisted the entire idea of a reservoir when it began gathering traction in the 1950s.

“I believe it took a miracle to get this project built,” Curtis-Sparks said.

The entire idea of a monstrous reservoir along the Sabine River apparently first arose in the late 1930s, evidenced by a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers study cited by Bob Bowman in “The Gift of Las Sabinas.”

Amazingly, the idea was shot down by corps researchers, who reported a lake wasn’t feasible.

The idea of harnessing the river again surfaced with the creation of the Sabine River Authority of Texas in 1949. Louisiana followed suit the following year with SRA-Louisiana.

According to Bowman’s historical treatise, both groups were “charged by their respective states with the duties of conserving and developing for beneficial purposes the waters of the (Sabine) river.”

Work between the two states, in conjunction with federal authorities, resulted in the ratification of a compact ratified by the Texas Legislature in 1953 and Louisiana Legislature in 1954.

The two SRAs signed a 1955 memorandum of agreement paving the way for equal financial support by the states for engineering and other business necessary to the creation of the reservoir.

The states also agreed to file a joint application for a $150,000 federal planning loan to allow a feasibility study of the project, Bowman’s book recounts.

That study ultimately deemed a reservoir not only feasible but economically justified.

“The cost of the project at the time of the study was estimated at $54,506,000,” Bowman wrote. “As a result, the two authorities adopted an overall budget of ($60 million).”

Support groups were popping up in local communities, with one of the primary Louisiana groups being the Toledo Development Association led by Many attorney John P. Godfrey.

The association’s dream, quoted by Bowman, was simple: “A Louisiana-Texas project backed by exhaustive studies of professional engineers to dam the Sabine River at a point 18 miles west of Leesville, Louisiana, … and create a 181,000-acre lake with a 650-mile shoreline in Louisiana … to relieve the depressed economic conditions, create hydroelectric power, produce water for industrial development and municipal use and provide the greatest tourist attraction in the South.”

However, local opposition remained strong. One such opponent was a Many resident named Cliff Ammons.

“I was reluctant to accept the idea at first because the reservoir was going to cover a portion of my old home place and farm,” the late Ammons wrote in a 1979 article in The Sabine Index.

However, after looking over the feasibility study, Ammons met one of its authors and switched sides.

“(James Cotton) explained the study and really sold me on the wonderful prospect,” Ammons explained.

Ammons traveled to Lake Texoma along the Texas-Oklahoma border to learn first-hand what a reservoir can mean to a community, and recorded stories of the economic boom local businesses experienced after that reservoir was formed.

He returned to Many a true believer.

“… I placed the recorder with the (audio) tapes in the barber shops, and they were played over and over again,” Ammons reported.

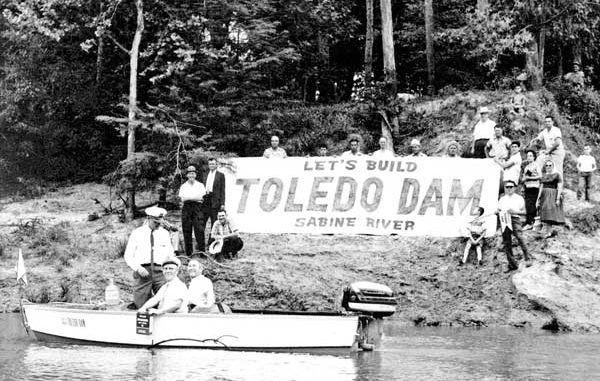

It was at that point that Louisiana politics really kicked in. Ammons ran for the Louisiana House of Representatives with a platform based around the motto “Let’s Build Toledo Bend Dam.”

Despite opposition and lack of political experience, Ammon won.

The political newbie went to Baton Rouge ready to introduce a bill approving reservoir funding, but he quickly was told to back down during a meeting with other west-Louisiana legislators, the head of the state Public Works Department, state engineers and a group of attorneys.

“When I asked the question, ‘What bill could I introduce to build Toledo Dam?’ (Public Works Department head Lawrence Wimbley) replied it was the wrong time to introduce any legislation requiring money, as the state was broke and it would require an experienced politician to try such an undertaking,” Ammons recalled. “Other legislators chimed in and agreed.

“After listening attentively for about one hour to all their comments, I said, ‘Gentlemen, I called the meeting for you to tell me what could be done to build Toledo Bend but all you have told me is what not to do.”

The meeting broke up after Wimbley “shook his finger at me” and accused Ammons of being a new legislator who did “not have the slightest idea what it would take to get this type of legislation passed. If you do introduce such a bill, you are going to hang yourself on the highest tree around this Capitol, and furthermore you are going to be the laughingstock of the whole Legislature.”

However, an attorney at the meeting, Fred Benton Jr., helped Ammons find a potential source for Louisiana’s $15 million share of construction in contested mineral rights escrow, but in the end state voters approved use of income from a pension-fund tax established in 1890 for Louisiana’s Civil War veterans.

“There was only one remaining (Civil War) widow in the mid 1950s,” Curtis-Sparks said.

Legislation approving the project, however, still faced stiff opposition. While Ammons battled in the Legislature to keep his bill alive and prevent crippling amendments, women back home were rallying to the cause.

“Garden Clubs were very prevalent in Louisiana at that time,” Curtis-Sparks said. “They did chain letters to other Garden Clubs, so you had this massive chain-letter thing going on in support of the project.”

One group went to Logansport and filled small glass bottles with Sabine River water.

“That’s what they took all over the state, giving them out,” Curtis-Sparks said.

The effort ultimately was successful, and the bill moved through both houses of the Legislature.

Once funding was secured and the appropriate legislation approved, all that was left was the actual construction of the dam.

However, Ammons paid a price for his successful battle to turn the dream into reality.

“He was defeated the next year,” Curtis-Sparks explained. “A lot of locals did not support the project.”