Marsh fishermen are well aware that Louisiana has lots of crabs. They seem to be everywhere in fresh, brackish and salt marshes, and end up being guests of honor at countless seafood boils in coastal Louisiana. These are almost always blue crabs, technically called Callinectes sapidus.

But Louisiana’s salt marshes do hold another large species of edible crab, and in numbers greater than the average person realizes. These are the Gulf stone crab, Menippe adina, a close relative of the Florida stone crab, Menippe mercenaria, that are so famous in Florida restaurants.

Once quite uncommon in Louisiana, Gulf stone crab populations have steadily increased since the late 1970s. Reasons for the increase are unclear. We could probably blame global warming since it seems to be causing everything else, but that likely isn’t the reason. More than likely, the growing population of stone crabs is due to larger areas of Louisiana’s marshes converting from brackish to saline marshes as our coastline sinks.

Our stone crab differs from the Florida version in that it is has a dark brown body compared to a tan or gray body for the Florida crab, and ours does not have stripes around its walking legs. While individual claws from our stone crabs are typically smaller than those of the Florida crab, it isn’t impossible to find half-pound claws on our critters.

Gulf stone crabs seem to prefer higher salinities than do blue crabs, never any lower than 10 parts per thousand (ppt) salt. By comparison, full strength sea water is 35 ppt. They are most common at salinities approaching 35 ppt, but are seldom found offshore.

Gulf stone crabs show a preference for areas near or on oyster reefs, rock jetties or debris-cluttered bottoms. There, they build burrows in the mud. The burrows are used for shelter, cold-weather refuge and when they molt their shells.

During cold months, they seem to show a preference for deeper channels and passes. Research indicates that they can survive very low oxygen levels for at least a day or two. Females seem to outnumber males, especially in deeper waters.

Mating is similar to that in blue crabs, taking place while the female is in the soft-shell stage, with the male cradling the female beneath him. A male will begin “guarding” a female before she molts and will continue to do so until her shell hardens. Mating is thought to take place in the fall.

The following spring, females will deposit their fertilized eggs on the “hairs” under their belly aprons in a large mass called a “sponge.” Hatching occurs in 7-18 days. Females spawn several times between March and September, with peak spawning occurring from May through June. After hatching, the larvae drift with tides and currents, and go though seven stages before they finally resemble adult crabs.

Once they settle to the bottom, young stone crabs eat a varied diet that includes oysters, mussels, snails, clams, worms, jellyfish, blue crabs, hermit crabs and plant matter. Shellfish of all kinds are important foods for adults, with oysters being a major food item. Feeding is highest on oyster spat and small oysters, but large adult stone crabs will eat oysters of all sizes. It has been estimated that a stone crab will eat an average of 219 oysters per year.

Gulf stone crabs grow fairly slowly. Some females are mature enough to spawn by age 2, but by age 3, still only 30 percent are mature. Only by age 7 are most females sexually mature. Harvesting only the claws of stone crabs does allow the creatures to survive harvesting (if properly done), but claw removal does slow their growth rate somewhat.

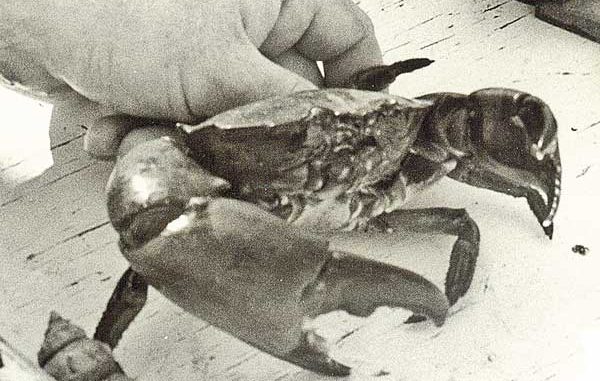

Stone crabs have a large crusher claw and a smaller pincer claw. Both can be legally harvested in Louisiana if the last joint of the claw, measured from the tip of the pincher to the first joint, is at least 2¾ inches long. Claws on males are longer and more slender than females’ claws.

Claws should be removed by grasping the animal and holding it facing away from the person’s body. While one hand holds the rest of the crab firmly, the second hand, holding the claw to be removed, should slowly, but firmly force the claw downward. The crab will actually break the claw off itself at a weak spot in the shell.

The claw should not be wrenched or twisted downward or, for that matter, in any direction, or it may kill the crab. Let the crab do the work. After the claw or claws have been removed, the crab should be returned to the water. Louisiana law provides that only claws from stone crabs may be landed.

Campers and weekend visitors often bring crab traps with them during visits to the coast. When set in areas likely to hold stone crabs, such as near rock jetties, stone crabs are a common treat. Often, unknowing fishermen dump them back in the water without knowing their delectable taste.

Another bonanza for anglers is the fact that stone crabs flock to mossy, weedy derelict crab traps that have been lost by crabbers. Some of these will actually yield as many as a dozen of these creatures with their huge heavy claws. Most coastal fishermen will at one time or another come across such a trap.

Stone crab claws have an incredibly rich flavor. Heresy to South Louisianans, this is one of the few crustaceans that tastes better boiled in lightly salted water rather than in traditional crab boil seasonings. Stone crab claw meat is traditionally dipped in melted butter after the hard shell is cracked.

Jerald Horst is author of the newly published Trout Masters: How Louisiana’s best anglers catch the lunkers. For ordering information, visit www.lasmag.com or call (800) 538-4355.