Find the cleanest water in a dirty-water area, and you’ll find the mother lode of redfish.

His questions seemed genuinely inquisitive rather than rhetorical. He actually listened to the answers, calmly and earnestly. He smilingly admitted much ignorance on several subjects. His tone of voice and facial expression were utterly free of cynicism.

He did not boast expertise in every field of human endeavor from hunting to fishing, from frogging to spearfishing, and from hydromechanics to microbiology. His demeanor and manner of speaking revealed no trace of bravado or know-it-allism.

There seemed only one explanation for this bizarre speech and behavior pattern: The fellow was obviously from out-of-state.

We were standing in front of a display at the Louisiana Sportsmen’s Show, and could hear the gentleman’s discourse with a local fishing guide of tremendous and well-earned repute.

“Well, March isn’t usually our best month for reds,” answered the guide in a sincere effort to manage the gentleman’s expectations.

“Bu*****t!” blurted Eddie, who was standing not 5 feet from them but looked at Pelayo and me while detonating his comment. The guide and gentleman looked over with a slightly puzzled look as Eddie made like he was sneezing.

The guide frowned but quickly resumed his conversation on redfish. This further confirmed my hunch that the friendly and inquisitive gentleman was from out-of-state. Most visiting fishermen scratch their heads and frown at our fetish for the feeble-fighting, parasite-ridden spotted seatrout.

When they go out in our marshes they want shallow water, spool-stripping reds, the kind they pay out the wazoo to catch (a pair of, if lucky) in the Florida Keys or coastal Everglades.

“Don’t get me wrong,” continued the guide. “We catch them year ’round, but we tend to do better in summer and especially in the fall when … .”

“Bu*****t!!”

Eddie, who was finishing his third, $7 beer, blurted even louder this time. But his sneezing bit was transparently phony this time. So he grabbed Pelayo’s shoulder while gulping, wiped his foamy lip and snickered. I jerked my head around, and saw the guide looking over again and with a more annoyed look this time.

But in seconds, he turned back to his prospective customer who smiled and shrugged while turning back to the videos the guide had on display.

These videos positively mesmerized him (as they did us). The gentleman punctuated his astonished gaze with a sincere “Wow!” or “Golly!” every time the screen showed a red exploding on the surface or being heaved aboard to a round of whoops and back slaps from the appreciative crew.

Pelayo, Eddie and I, all locally raised, could never allow ourselves such unseemly histrionics in full view of people at a Sportsmen’s Show. We had to look unimpressed, sophisticated and “cool.” Like we experienced those things every time we put our boats in the water.

“Those are certainly some gorgeous redfish,” beamed the smiling gentleman as the video sputtered to an end.

“Anybody can catch redfish in March!” Eddie blurted while walking right behind the gentleman as he lumbered toward the beer booth. “Y’all ready?”

He looked over his shoulder at Pelayo and me while pointing at his beer.

Pelayo nodded, and the gentleman smiled warily, but I looked at the guide. His frowning eyes were locked on Eddie, and his face looked like Sonny Corleone’s when he got that call from Connie that Carlo was beating her up again. I could already see Eddie getting his kidneys kicked into mush and his head bashed in with a garbage-can lid until he expired under a spouting fire hydrant.

But, thank goodness, in seconds he seemed distantly safe, clumsily bulling through the crowd toward the beer booth.

Nobody ever called Eddie “Mr. Suave,” much less “Mr. Sensitive.” His wedding reception (first of three thus far) is still a classic among boozy, card-playing, hunting camp reminiscing.

Eric Clapton’s “Wonderful Tonight” is also a classic at wedding receptions. The bride and groom take to the dance floor as the crowd (female portion from the blue-haired Na-Nas to the bridesmaids, mostly) all circle around holding hands, smiling dreamily, some hugging, many wiping their eyes.

Well, sure enough, the song came on at Eddie’s. The above scene unfolded like clockwork, but Eddie suddenly broke away from his bride’s embrace, rushed over and leaped atop the stage, seizing the DJ roughly by the shoulders. A rustle of nervous laughter erupted in the huge hall, but soon you could hear a pin drop in the place as Eddie rummaged through the CDs.

Finally he jerked one out, shoved it in front of the DJ’s startled face, pointed out a song and leaped back off the stage with a demented grin on his crimson face.

Most of the guys instantly recognized the opening notes of Tom Petty’s “You Got Lucky, Babe!” We looked at each other not knowing whether to laugh or run for cover under the tables as the women caught on. When Eddie started bellowing the lyrics in manner to shame the most shameless drunkard in the loudest karaoke bar, we knew we should have opted for the latter.

“Good love is hard to find. You GOT LUCKY BABE!” Eddie snarled the lyrics and accentuated the words with vigorous arm and hand motions as he took center stage on the dance floor. Initially, his groomsmen whooped and high-fived, but soon they noticed the weeping bride being hustled off by her mother and bridesmaids. Our own wives’ facial expressions seemed to demonstrate solidarity with the bride — so soon we ALL ran for cover.

That marriage lasted three months — which was exactly 89 days and 22 hours longer than I expected Eddie’s life to run if he kept up his antics at the Sportsmen’s Show.

Eddie might have explained it a tad more tactfully at the show, but he had a point. March “roars in like a lion and creeps out like a lamb,” they say. In South Louisiana, that process generates many days of hellacious southeast winds — right before a front and usually starting again about two days after it. When these weak fronts sputter out, those southeast winds just continue unabated, pushing high tides into our marshes.

Those high tides, as we all know, push redfish into the shallowest portions of our coastal marshes, and make for the most exciting type of redfishing. When hooked in 2 feet of water, a redfish cannot go down; he can only streak off on a berserk, line-stripping run that literally epitomizes what the thrill of coastal fishing is all about.

Nothing else comes close.

In our experience, some of the best chances to experience those runs come with those high coastal tides in March.

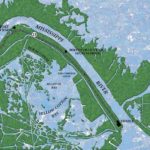

But some planning is called for. For instance, in March the Mississippi is high and the wind (as mentioned) typically out of the southeast. The muddy river water gushes into the Gulf from Red, Tante Phine, Tiger and Southwest passes on the west side and through the breaks below the Ostrica locks (the locks themselves, nowadays), Baptiste Collette, Main Pass and Pass a Loutre on the east side.

The southeast wind and a rising tide then inundate the coastal marshes with the muddy but magic elixir. It’s good in the long run, but it makes for tough fishing while it’s flooding the marsh.

Consequently, in March we find it important to fish these areas during a falling tide. On the west side, such a tidal movement brings down the clearer water from up around the Buras Canal and Hospital-Yellow Cotton Bay areas to the regions closer to the coast, and puts the fish into a feeding frenzy. Same process on the east as the ponds in the Biloxi and Delacroix marshes empty.

Notice I didn’t say “clear” water. I said “clearer,” as in compared to river water. In relatively open, wind-buffeted marshes this time of year, you’ll never really get clear water — say, as in the usual clarity in ponds and bayous in the Biloxi Marsh or upper Cocodrie and Lafitte areas.

Nothing even close. Clear for us means about 3 inches of visibility. For our brand of redfishing (shrimp-baited jigs under corks, cast close to the shore and current lines), if we can see the top of our prop, we’re in business.

Actually the generally murky water greatly simplifies things. Simply find pockets of clearer water, and the fish will often be stacked up within them.

The morning after the show, Eddie bugged out so Pelayo’s brother-in-law, Zach, accompanied us to fish the roseau-bordered area between Tessiers Bend and Buras Bayou in the pocket of water between Baptiste Collette and Main Pass.

Unlike much of the rest of the Delta region, during high river stage the water in this area remains fishably clear (not green like in September, but with those few inches of visibility we prefer).

Oddly, during the traditionally hot months for Delta reds (September, October and November) when the river’s low and the entire area’s water a pretty green, this area on the east side of the river yields few reds (as has the Delta in general for us lately during those months).

But from February through May, we generally have good catches — a pattern that upends traditional Delta dogma.

Pelayo was at the helm as we left the marina.

“SLOW DOWN!” I motioned from the bow, knowing I was wasting my breath. Navigating the Jump is never pleasant. Now poor Zach was holding on with white knuckles and coughing violently from the cloud of diesel fumes discharged by a supply boat Pelayo insisted on trying to pass. He’d just lost his cap, and there was no question of turning around to retrieve it. Waves smacked us from all sides — from a crewboat on the left, from a shrimp boat on the right, from a tug washing over the transom and from a howling southeaster coming straight up Grand Pass whacking the bow.

The turmoil dangerously agitating digestive systems made full and unstable by the night’s gluttony and drink. Bathrooms in marinas receded behind us. A concerned look was evident on several faces.

Somehow we made it. We hung a right into Emiline Pass just as some color returned to Zach’s face. Then we hung a right into the pipeline with mountainous spoil banks near the end, and followed the posts and barrels into the open water, which was still filthy.

The water was still unfishably dirty near the mouth of Romere Pass. So we continued east. Shortly, Pelayo grabbed my shoulder.

“Look at the prop wash,” he signaled with a nod.

The foam was almost white. We slowed down and — INDEED! — we could make out the top of the prop. We bellowed our excitement to the heavens, all except Zach.

“THIS is CLEAR?!” he snorted. “Geezum, what do you guys call dirty?”

“We’re not flyfishing or top-water fishing out here, Zach,” Pelayo rasped while baiting up his chartreuse beetle. “This is redfish water, believe me.”

For successful redfishing, we always look for what we term the “Holy Trinity:” 1) clear water; 2) depths of 18 to 24 inches close to the shore; and 3) moving water (a slight current).

Here we found them all, as Pelayo cast to a cut in the roseaus with water moving out. Many such cuts mark this area.

I also cast out near the cut’s mouth with a nice hunk of shrimp on a purple/chartreuse beetle 2 feet under a popping cork, watched it bob in the current and handed it to Zach.

“Hold this while I rig one up for you,” I said.

“Where’s the … cork … ?” I asked while reaching in the tackle box.

“The CORK, Zach!” Pelayo bellowed. “Set the HOOK! Set it, man!”

So Zach started frantically reeling in the slack, then raced back.

“WHOA!”

“That’s him, Zach! That’s him!”

“Ride him out, Zach, my boy!” Pelayo screeched. “Ride him out.”

The reel sang its sweet music as the brute aimed for Main Pass.

“Man, oh man. Awesome,” was all Zach could manage.

But the look on his face said much more. The man was aglow. Then the fish hit the surface about 50 yards out with a breathtaking eruption of froth and copper.

“WHAT … A … FISH!”

Latch a man to a feisty red in shallow water with light tackle, and you’ve got a fisherman for life. The red aimed back for the roseaus with a spirited run. Then back north. Finally Zach started gaining on him.

“Another one — HERE!” Pelayo grunted. And he set the hook with the “here.”

“Another monster!” he announced. It exploded on the surface, and made for Breton Island.

Two reels singing, and I hadn’t even cast. To heck with netting them, I decided. They can net their own. I’m fishing. And out went my shrimp-tipped beetle toward the edge of the roseau. I turned to watch Zach, who was still locked in battle. Then I looked back. Well, now where’s MY cork?!

“YUP!!”

Then that gratifying lunge as the red felt the hook. But this sucker plowed into a thin stand of roseaus before I could turn him. He was plowing through them like a nutria, and finally came out, but with my line hung on three canes. Oh Lord, I thought. Let’s see, he lunged again and again, and they came free.

“Great!” I thought to myself.

Zach was swinging his 3-pounder aboard as I passed him on my way to the bow where I stood howling to the heavens with my pole high while savoring every drag-singing inch of this brute’s runs and lunges.

When we lifted the anchor half an hour later, six reds from 3 to 9 pounds lay in the box. We moved to four more similar spots, and ended with 13. No limit, but a couple of beautiful puppy drum and two sheepshead gave us 17 delectable fish for the grill.

Never fails: High, dirty springtime water actually simplifies our fishing. These fish were ganged up in the (relatively) clear and current-washed pockets.